Highway war, pothole world: how roads are built in different countries. Railroad history

Introduction. 3

1. Roads to Kievan Rus. 4

2. Territorial growth of Russia and development of roads. 6

3. Large road construction projects of the 18th–19th centuries. 7

4. Russian roads in the twentieth century. nine

Conclusion. fourteen

List of references.. 15

Introduction

Anyone who thinks that roads appeared on our planet recently is very mistaken. There have always been roads, even when there was no man himself on Earth. Animals, for example, always ran to the watering hole along the relatively trampled by them safe roads without risking falling into a deep hole or drowning in a swamp. But a man came. He was no longer satisfied with the spontaneously formed and narrow paths passing through forests and mountains. A person had to move not only on his own, but also to come up with something so that the carts he made would not get stuck in the mud during the autumn thaw. And the man began to build roads. At first it was just narrow and long strips paved with cobblestones or pieces of sandstone. But, over the centuries, roads have been improved, and today they are multi-lane structures with their own infrastructure, interchanges, bridges across water barriers, many kilometers of tunnels pierced in the mountains and lying under water. All of these are roads.

The history of road construction itself is like a long and winding road. In this paper, we will consider the history of one of its sections - the history of Russian roads.

Roads are one of the most important elements state infrastructure. The degree of development of the road network directly affects the economic prosperity and defense capability of the country.

Unfortunately, throughout history, Russian roads have left much to be desired. To some extent, this is due to the peculiarity of the natural and geographical conditions in which Russian civilization was formed. Due to the harsh climate, the presence a large number various kinds of obstacles - forests, wetlands, the construction of roads in Russia has always been associated with significant difficulties. Unlike the countries of the West, which arose on the site of one of the greatest ancient civilizations - ancient rome and inherited from it, in addition to Roman law and architecture, an excellent road system, Russian civilization, being peripheral, arose on a rich but undeveloped territory, which also explains the peculiarities of the development of its transport system.

By the end of the ninth century, the education ancient Russian state. In view of the fact that most of the territory of Russia was occupied by impenetrable forests, rivers played the role of roads; all Russian cities and most of the villages were located along the banks of the rivers. In the summer they swam along the rivers, in the winter they rode sledges. According to the testimony of the Byzantine emperor of the 10th century, Constantine Porphyrogenitus, even the collection of tribute by the Kiev prince (polyudye) was carried out in winter time. In November, the prince with a retinue left Kyiv and traveled around the subject territories, returning in April. Apparently, in the rest of the year, many Russian territories were simply inaccessible. Overland communication was also hampered by gangs of robbers who hunted on forest roads. Kyiv prince Vladimir Monomakh, who ruled in early XII century, in his “Instruction”, addressed to his children, as one of his exploits, he recalled the journey “through the Vyatichi” - through the land of the Vyatichi. The first mention of road works refers to the year 1015. According to The Tale of Bygone Years, Kyiv prince Vladimir, going on a campaign against his son Yaroslav, who reigned in Novgorod, ordered his servants: "Pull the paths and bridge." In the 11th century, the authorities tried to legislate the status of "bridgemen" - masters in the construction and repair of bridges and pavements. The first written set of laws in Russia, Russkaya Pravda, contains a Lesson for Bridgemen, which, among other things, set tariffs for various road works.

The absence of roads sometimes turned out to be a boon for the population of the Russian principalities. So, in 1238, Batu Khan, who ruined the Ryazan and Vladimir-Suzdal principalities, could not reach Novgorod due to the spring thaw, and was forced to turn south. Tatar-Mongol invasion played a dual role in the development road system Russian lands. On the one hand, as a result of Batu’s campaigns, the economy of the Russian principalities was thoroughly undermined, dozens of cities were destroyed, a significant part of the population died or was taken prisoner, which ultimately led to a reduction in trade and desolation of roads. At the same time, having subjugated North-Eastern Russia and made it an ulus (part) of the Golden Horde, the Tatars introduced their postal system in the Russian lands, borrowed from China, which in fact was a revolution in the development of the road network. Horde mail stations began to be located along the roads, called pits (from the Mongolian "dzyam" - "road"). The owners of the stations were called coachmen (from the Turkic "yamdzhi" - "messenger"). The maintenance of the pits fell on the local population, who also performed the underwater duty, i.e. was obliged to provide their horses and carts to the Horde ambassadors or messengers. Horde officials traveling along Russian roads were issued a special pass - a paysatz.

2. Territorial growth of Russia and development of roads

XIV-XV centuries in the history of Russia - the time of the formation of a single centralized state. The Moscow Principality unites the lands of North-Eastern Russia around itself; at the end of the 15th century, a new name for a single state appeared - “Russia”. The growth of the territory of Russia continued in the XVI-XVII centuries. By the end of the 16th century, the Volga, Urals, Western Siberia. In connection with the growth of the territory, roads in Russia have acquired special importance; on them, messengers from all the outskirts of the state delivered to Moscow news of the invasions of foreign troops, rebellions and crop failures. The central government showed particular concern for the development of the Yamskaya post, inherited from the Tatars. In the 16th century, yamskaya chase was established in the Ryazan and Smolensk lands. By the time of the reign of Ivan III, the first surviving travel letter issued to Yuri Grek and Kulka Oksentiev, who was sent "to the Germans", dates back. In it, the sovereign ordered at the entire distance from Moscow to Tver, from Tver to Torzhok and from Torzhok to Novgorod to give ambassadors "two carts each to the carts from the pit to the doyam according to this letter of mine." In another letter of Ivan III - dated June 6, 1481 - the position of an official responsible for the condition of postal stations and roads - a Yamsk bailiff, was first mentioned. The pits were located at a distance of 30-50 miles. Coachmen were obliged to provide horses for all travelers with a princely letter, for their service they were exempted from tax - the sovereign tax and all duties - and, moreover, received maintenance in money and oats. Local peasants had to keep the roads in good condition under the supervision of coachmen. At the choice of the headman, two people from the plow (a territorial unit of tax payment) went out to clear roads, repair bridges and renew the gates through the swampy sections of the road. Under Ivan the Terrible, in 1555, a single body for managing the road business was created - the Yamskaya hut. Already at the beginning of the 16th century, the first descriptions of large Russian roads appeared - “Russian road builder”, “Perm” and “Yugorsky” road builders. By the end of the 16th century, “exiled books” appeared with descriptions of small regional roads.

3. Large road construction projects of the 18th–19th centuries.

In the Petrine era, road supervision passed to the Chamber Collegium, the central tax department, which also collected road tolls. In the localities, in the provinces and provinces, the roads were entrusted to zemstvo commissars, who were elected by local landowners and subordinate to the Chamber Collegium. The largest road construction project of the time of Peter the Great was undoubtedly the construction of a "prospective" - straight-line road from St. Petersburg to Moscow. Work on the construction of the "prospective" road continued until 1746. The road work was in charge of the Office of the State Road Construction, headed by General V.V. Fermor.

Catherine II, already at the beginning of her reign, decided to give the road business the character of an important state task. It strengthened the status of the Chancellery from the construction of state roads as a central institution. The decree of February 18, 1764 ordered her to "make efforts to bring all state roads into the best condition." In 1775, a provincial reform was carried out. Most of the central departments, including the Office for the Construction of State Roads, are gradually being liquidated, their powers are being transferred to provinces and counties. The authorities of the province were supposed to deal only with the completion of state roads, and their maintenance was transferred to the county authorities - the zemstvo police officer and the lower zemstvo court. They were instructed to “apply vigilant watch and care so that roads, bridges and crossings ... are kept in such good condition so that there is no stopping or danger for the passers-by”, so that “no one dug up bridges and roads, blocked or shifted from one places to another ... and so that everywhere on roads and bridges there is cleanliness, and dead cattle and carrion, from which a harmful spirit emanates ... not lying anywhere.

During the XVIII-XIX centuries, the road departments were subjected to constant reorganization. In 1809, Alexander I approved the Institution for the management of water and land communications. According to him, the Expedition of Water Communications and the Expedition for the Construction of Roads in the State merged into the Directorate of Water and Land Communications (since 1810 - the Main Directorate of Communications - GUPS), which was entrusted with all communications of national importance. The administration was located in Tver, headed by chief director and advice. Under the chief director there was an expedition, which included three categories (departments), of which the second was engaged in overland roads. The empire was divided into 10 districts of communications. At the head of the district was the district chief, who was subordinate to the managing directors who supervised the most important parts of the lines of communication and were especially busy drafting projects and estimates. The security of the roads has also been improved. It was entrusted to special district police teams, which were subordinate to the district chiefs. The teams consisted of the chief of police, caretakers, non-commissioned officers and privates. Their task was not to fight criminality, but to ensure that "roads, bridges, ditches, etc. were not damaged, that the side channels were not blocked, that the roads themselves were not narrowed by buildings, wattle fences or plowed."

In the second half of the 19th century, the importance of unpaved and highway roads in Russia, in connection with the development railway transport decreased significantly. If in 1840–1860 up to 266 miles of highways were put into operation annually, then in the 60s it was 2.5 times less. So, in 1860-1867, an average of 105 miles per year was built. In 1867–1876, there was practically no road construction, and from 1876 to 1883, no more than 15 versts of the highway were put into operation annually. In addition, the quality and condition of these roads left much to be desired. The situation changed somewhat after the Zemstvo reform in 1864. The roads were transferred to the jurisdiction of the zemstvos, which were supposed to monitor their serviceability. Lacking the large funds necessary for carrying out large-scale road works, the zemstvos launched a vigorous activity to improve roads. Along the roads begin to form green spaces, road equipment is purchased abroad.

4. Russian roads in the twentieth century

The rapid development of the country's industry at the turn of the 19th–20th centuries, as well as the appearance of the first cars on Russian roads contributed to changing the attitude of the government towards the condition of the road network. Before the First World War, car races were organized almost every year, local authorities tried to improve the roads before these events. Many dignitaries, generals, senior officials contributed to the allocation of financial and material resources for the construction of roads, as well as the solution of various organizational problems. The measures taken at the beginning of the 20th century by the government, zemstvos, commercial, industrial and financial circles made it possible to slightly increase the length of the road network, improve their condition, and introduce some technological innovations.

The revolutions of 1917 and the civil war of 1918-1920 had a huge impact on the development of the country's road network. During the Civil War, road construction was carried out by Voenstroy, Frontstroy, and the Highway Administration (Upshoss) of the NKPS. After the end of the civil war, countless reorganizations of these departments began. At the beginning of 1922, Upshoss and the Central Automobile Section of the Supreme Council of National Economy were merged and included in the Central Administration of Local Transport (TSUMT) as part of the NKPS. However, already in August 1922, by a joint decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR, the country's road infrastructure was divided between two departments - the TSUMT NKPS and the Main Directorate of Communal Services (GUKH) of the NKVD. The roads of national importance were under the jurisdiction of TSUMT, the direct concern for the condition of the roads was entrusted to the district departments of local transport (OMES) subordinate to TSUMT. Departments of communal services GUKH NKVD carried out the management of local roads.

The reforms of the road management authorities continued in subsequent years. At the same time, the state of the road remained in a deplorable state. The problem of financing road construction was particularly acute. At the same time, the country that carried out industrialization needed to create a developed transport system as soon as possible. From the position Soviet leadership tried to get out by transferring control of the roads of the allied significance to the NKVD. In 1936, as part of the NKVD of the USSR, the Main Directorate of Highways (Gushosdor) was formed, which was in charge of roads of allied significance. As early as 1925, a natural road service was introduced in the country, according to which, local residents were obliged to work for free certain number days a year for road construction. In 1936, a government decree was issued, which recognized the expediency of creating permanent local brigades, whose work was counted in overall plan labor participation of collective farmers. However, the main labor force in the construction of roads were prisoners. As a result of the second five-year plan (1933-1937), the country received more than 230 thousand kilometers of profiled dirt roads. At the same time, the plan for the construction of paved roads turned out to be underfulfilled by 15%.

A large road construction program was planned for the third five-year plan (1938–1942), but the Great Patriotic War prevented its implementation. During the war years, a significant part of the road equipment was transferred to the Red Army, many road workers went to the front. During the hostilities, 91 thousand kilometers were destroyed highways, 90 thousand bridges with a total length of 980 kilometers, therefore, after the end of the war, the primary task facing the road services was the repair and restoration of roads. However, the fourth five-year plan, adopted in March 1946, poorly took into account the interests of the road industry, which was funded on a residual basis. At that time, two departments were responsible for the construction of roads - Gushosdor of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Main Road Administration (Glavdorupr). As part of Gushosdor in 1945, a Special Road Construction Corps was created, the basis of which was road troops.

In the 1950s, Gushosdor moved into the structure of the newly created Ministry of road transport and highways of the USSR, where it was divided into two main departments - operational (Gushosdor) and construction (Glavdorstroy). All work on the construction of national roads, which was previously carried out by Gushosdor, was transferred to Glavdorstroy. Problems with the financing of the road industry were felt in these years as well. Efforts continued to be made to involve the local population, various enterprises. In 1950, Glavdorupr was simultaneously building 32 roads of republican significance and a number of local roads. The dispersal of resources and the multi-objective nature of tasks with poor material and personnel support had a negative impact on the results of the work.

http://www.rosavtodor.ru/doc/history/main15.jpg The peak of road construction in the USSR falls on the 60-70s. The allocation of significant funds for road construction begins, road builders receive modern technology. In 1962, the Moscow Ring Road was put into operation, with a length of 109 kilometers. In general, in Russian Federation in 1959–1965, the length of paved roads increased by 81.2 thousand kilometers, 37 thousand kilometers of them had improved pavements. In the same years, the roads Kashira-Voronezh, Voronezh-Saratov, Voronezh-Shakhty, Saratov-Balashov, Vladimir-Ivanovo, Sverdlovsk-Chelyabinsk, and a number of others were built.

Intensive road construction continued in the 1970s and 1980s. As a result, in 1990 the road network common use in the RSFSR was 455.4 thousand kilometers, including 41 thousand kilometers of national roads and 57.6 thousand kilometers of republican significance.

However, in the early 1990s, about 167 district centers (out of 1837) were still not connected to regional and republican centers by paved roads. The residents of almost 1,700 central estates (out of 23,000) and about 250,000 medium, small settlements and farms. Due to the difficult economic situation in the country, there was a big shortage of financial resources. At the same time, the transition to a market economy required a revision and fundamental change in the essence of many socio-economic categories, such as the form of ownership, planning, management of industrial relations, the psychology of the individual and society, and many other components. human being.

Despite all the difficulties, for 1997-1999. there have been real shifts both in the development of the road network and in the efficiency of the functioning of the road sector. Over the past 12–13 years, Russia has seen an accelerated (up to 10% per year) growth in the car park, traffic intensity and road transport.

As of January 1, 2002, the length of motor roads in the Russian Federation was 904.7 thousand km, including 759.3 thousand km of paved roads and 145.4 thousand km of unpaved roads. The length of public roads is 588.7 thousand km, including 537.3 thousand km of paved roads (91%), unpaved roads - 51.4 thousand km. At the same time, the length of federal public roads is 46.6 thousand km, including 46.3 thousand km (99.3%) with a hard surface, and 542.1 thousand km of territorial public roads, in including hard-surfaced 491 thousand km (90%).

Yes, our roads are still inferior to European ones, and in general we do not have enough of them. Experts have calculated that in order to fully meet the socio-economic needs of the country, the minimum length of the Russian road network should be at least 1.5 million km, that is, increase one and a half times compared to what we already have.

Of course, this will require a significant increase in the volume of road construction. Here it is appropriate to quote the statement of Sergei Frank, Minister of Transport of the Russian Federation. He announced that the national program for the development of the road network envisages an increase in the total length of Russian roads by 2010 by 80,000 km. This task is supposed to be carried out with the involvement of private investors, who will have the opportunity to create a network of toll roads in our country.

However, those who are frightened by the very phrase "toll roads" can be reassured. Commercial highways will only be an alternative to the conventional road network. The appearance of toll roads will not change the quality of functioning of existing roads, and first of all, federal highways. The driver himself will decide whether to drive straight as an arrow and ideally flat road, for which you will have to pay, or use the free one, the quality of which has become familiar to us. This practice has long been accepted in many countries of the world. And, in my opinion, this is quite fair, as long as there are no excesses.

The road builders do not stop there and direct their main efforts to expanding not only the domestic, but also the international space. This is reflected in the federal target program "Modernization of the transport system of Russia (2002-2010)" being implemented today, namely in the part "Roads" (the program "Roads of Russia in the 21st century"), which is based on the principle of developing international and Russian transport corridors : Baltic-Center-South, Western border-Center-Ural, North-South, North-West-Ural, Western Siberia- Far East other. They play a central role in solving transport problems related to the expansion of international, interstate and interregional transport, economic, political, and cultural ties.

Currently, with the support of the Government of the Russian Federation, active work is underway on a long-term program for the development of the national network of Russian highways until 2025. New tasks are set, the main directions are determined, priorities are identified with one goal - to make Russia a country of developed motorization and excellent roads. Let's hope that this most difficult task will be completed not only in the central part, but also in the northern part of Russia, in the Far East and in Siberia.

1. Roads of Moscow [Electronic resource]: http://about-roads.ru/auto/moscow-roads/

2.Roads of Russia: trouble or victory [Electronic resource]: http://about-roads.ru/auto/autoroad-rus/2/

3.Roads of Russia: history and modernity [Electronic resource]: http://www.rosavtodor.ru/doc/history/hystory1.htm

4. History of roads in Russia and the world [Electronic resource]: http://about-roads.ru/auto/road-history/

Introduction. 3

1. Roads in Kievan Rus. 4

2. Territorial growth of Russia and development of roads. 6

3. Large road construction projects of the 18th–19th centuries. 7

4. Russian roads in the twentieth century. nine

Conclusion. fourteen

List of references.. 15

Introduction

Anyone who thinks that roads appeared on our planet recently is very mistaken. There have always been roads, even when there was no man himself on Earth. Animals, for example, always ran to the watering hole along the relatively safe roads they had trampled, without the risk of falling into a deep hole or drowning in a swamp. But a man came. He was no longer satisfied with the spontaneously formed and narrow paths passing through forests and mountains. A person had to move not only on his own, but also to come up with something so that the carts he made would not get stuck in the mud during the autumn thaw. And the man began to build roads. At first it was just narrow and long strips paved with cobblestones or pieces of sandstone. But, over the centuries, roads have been improved, and today they are multi-lane structures with their own infrastructure, interchanges, bridges across water barriers, many kilometers of tunnels pierced in the mountains and lying under water. All of these are roads.

The history of road construction itself is like a long and winding road. In this paper, we will consider the history of one of its sections - the history of Russian roads.

1. Roads in Kievan Rus

Roads are one of the most important elements of the state's infrastructure. The degree of development of the road network directly affects the economic prosperity and defense capability of the country.

Unfortunately, throughout history, Russian roads have left much to be desired. To some extent, this is due to the peculiarity of the natural and geographical conditions in which Russian civilization was formed. In view of the harsh climate, the presence of a large number of various kinds of obstacles - forests, wetlands, the construction of roads in Russia has always been associated with significant difficulties. Unlike Western countries, which arose on the site of one of the greatest ancient civilizations - Ancient Rome and inherited from it, in addition to Roman law and architecture, an excellent road system, Russian civilization, being peripheral, arose on a rich but undeveloped territory, which also explains the peculiarities of its development. transport system.

The formation of the Old Russian state dates back to the end of the 9th century. In view of the fact that most of the territory of Russia was occupied by impenetrable forests, rivers played the role of roads; all Russian cities and most of the villages were located along the banks of the rivers. In the summer they swam along the rivers, in the winter they rode sledges. According to the testimony of the Byzantine emperor of the 10th century, Constantine Porphyrogenitus, even the collection of tribute by the Kiev prince (poludie) was carried out in winter. In November, the prince with a retinue left Kyiv and traveled around the subject territories, returning in April. Apparently, in the rest of the year, many Russian territories were simply inaccessible. Overland communication was also hampered by gangs of robbers who hunted on forest roads. Kyiv Prince Vladimir Monomakh, who ruled at the beginning of the 12th century, in his "Instruction" addressed to his children, as one of his exploits, recalled the journey "through the Vyatichi" - through the land of the Vyatichi. The first mention of road works dates back to 1015. According to The Tale of Bygone Years, Prince Vladimir of Kyiv, preparing to go on a campaign against his son Yaroslav, who reigned in Novgorod, ordered his servants: “Pull the paths and bridge the bridges.” In the 11th century, the authorities tried to legislate the status of "bridgemen" - masters in the construction and repair of bridges and pavements. The first written set of laws in Russia, Russkaya Pravda, contains a Lesson for Bridgemen, which, among other things, set tariffs for various road works.

The absence of roads sometimes turned out to be a boon for the population of the Russian principalities. So, in 1238, Batu Khan, who ruined the Ryazan and Vladimir-Suzdal principalities, could not reach Novgorod due to the spring thaw, and was forced to turn south. The Tatar-Mongol invasion played a dual role in the development of the road system of the Russian lands. On the one hand, as a result of Batu’s campaigns, the economy of the Russian principalities was thoroughly undermined, dozens of cities were destroyed, a significant part of the population died or was taken prisoner, which ultimately led to a reduction in trade and desolation of roads. At the same time, having subjugated North-Eastern Russia and made it an ulus (part) of the Golden Horde, the Tatars introduced their postal system in the Russian lands, borrowed from China, which in fact was a revolution in the development of the road network. Horde mail stations began to be located along the roads, called pits (from the Mongolian "dzyam" - "road"). The owners of the stations were called coachmen (from the Turkic "yamdzhi" - "messenger"). The maintenance of the pits fell on the local population, who also performed the underwater duty, i.e. was obliged to provide their horses and carts to the Horde ambassadors or messengers. Horde officials traveling along Russian roads were issued a special pass - a paysatz.

2. Territorial growth of Russia and development of roads

XIV-XV centuries in the history of Russia - the time of the formation of a single centralized state. The Moscow Principality unites the lands of North-Eastern Russia around itself; at the end of the 15th century, a new name for a single state appeared - “Russia”. The growth of the territory of Russia continued in the XVI-XVII centuries. By the end of the 16th century, the Volga, Urals, and Western Siberia were included in Russia. In connection with the growth of the territory, roads in Russia have acquired special importance; on them, messengers from all the outskirts of the state delivered to Moscow news of the invasions of foreign troops, rebellions and crop failures. The central government showed particular concern for the development of the Yamskaya post, inherited from the Tatars. In the 16th century, yamskaya chase was established in the Ryazan and Smolensk lands. By the time of the reign of Ivan III, the first surviving travel letter issued to Yuri Grek and Kulka Oksentiev, who was sent "to the Germans", dates back. In it, the sovereign ordered at all distances from Moscow to Tver, from Tver to Torzhok and from Torzhok to Novgorod to give ambassadors "two carts to carts from pit to pit according to this letter of mine." In another letter of Ivan III - dated June 6, 1481 - the position of an official responsible for the condition of postal stations and roads - a Yamsk bailiff, was first mentioned. The pits were located at a distance of 30-50 miles. Coachmen were obliged to provide horses for all travelers with a princely letter, for their service they were exempted from tax - the sovereign tax and all duties - and, moreover, received maintenance in money and oats. Local peasants had to keep the roads in good condition under the supervision of coachmen. At the choice of the headman, two people from the plow (a territorial unit of tax payment) went out to clear roads, repair bridges and renew the gates through the swampy sections of the road. Under Ivan the Terrible, in 1555, a single body for managing the road business was created - the Yamskaya hut. Already at the beginning of the 16th century, the first descriptions of large Russian roads appeared - “Russian road builder”, “Perm” and “Yugorsky” road builders. By the end of the 16th century, “exiled books” appeared with descriptions of small regional roads.

3. Large road construction projects of the 18th–19th centuries.

In the Petrine era, road supervision passed to the Chamber Collegium, the central tax department, which also collected road tolls. In the localities, in the provinces and provinces, the roads were entrusted to zemstvo commissars, who were elected by local landowners and subordinate to the Chamber Collegium. The largest road construction project of the time of Peter the Great was undoubtedly the construction of a "prospective" - straight-line road from St. Petersburg to Moscow. Work on the construction of the "prospective" road continued until 1746. The road work was in charge of the Office of the State Road Construction, headed by General V.V. Fermor.

Catherine II, already at the beginning of her reign, decided to give the road business the character of an important state task. It strengthened the status of the Chancellery from the construction of state roads as a central institution. The decree of February 18, 1764 ordered her to "make efforts to bring all state roads to the best condition." In 1775, a provincial reform was carried out. Most of the central departments, including the Office for the Construction of State Roads, are gradually being liquidated, their powers are being transferred to provinces and counties. The authorities of the province were supposed to deal only with the completion of state roads, and their maintenance was transferred to the county authorities - the zemstvo police officer and the lower zemstvo court. They were instructed to “apply vigilant watch and care so that roads, bridges and crossings ... are kept in such good condition so that there is no stopping or danger for the passers-by”, so that “no one dug up bridges and roads, blocked or shifted from one places to another ... and so that everywhere on roads and bridges there is cleanliness, and dead cattle and carrion, from which a harmful spirit emanates ... not lying anywhere.

During the XVIII-XIX centuries, the road departments were subjected to constant reorganization. In 1809, Alexander I approved the Institution for the management of water and land communications. According to him, the Expedition of Water Communications and the Expedition for the Construction of Roads in the State merged into the Directorate of Water and Land Communications (since 1810 - the Main Directorate of Communications - GUPS), which was entrusted with all communications of national importance. The department was located in Tver, headed by the chief director and the council. Under the chief director there was an expedition, which included three categories (departments), of which the second was engaged in overland roads. The empire was divided into 10 districts of communications. At the head of the district was the district chief, who was subordinate to the managing directors who supervised the most important parts of the lines of communication and were especially busy drafting projects and estimates. The security of the roads has also been improved. It was entrusted to special district police teams, which were subordinate to the district chiefs. The teams consisted of the chief of police, caretakers, non-commissioned officers and privates. Their task was not to fight criminality, but to ensure that "roads, bridges, ditches, etc. were not damaged, that the side channels were not blocked, that the roads themselves were not narrowed by buildings, wattle fences or plowed."

In the second half of the 19th century, the importance of unpaved and highway roads in Russia decreased significantly due to the development of railway transport. If in 1840–1860 up to 266 miles of highways were put into operation annually, then in the 60s it was 2.5 times less. So, in 1860-1867, an average of 105 miles per year was built. In 1867–1876, there was practically no road construction, and from 1876 to 1883, no more than 15 versts of the highway were put into operation annually. In addition, the quality and condition of these roads left much to be desired. The situation changed somewhat after the Zemstvo reform in 1864. The roads were transferred to the jurisdiction of the zemstvos, which were supposed to monitor their serviceability. Lacking the large funds necessary for carrying out large-scale road works, the zemstvos launched a vigorous activity to improve roads. Green spaces are being created along the roads, road equipment is being purchased abroad.

4. Russian roads in the twentieth century

The rapid development of the country's industry at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries, as well as the appearance of the first cars on Russian roads, contributed to a change in the attitude of the government to the state of the road network. Before the First World War, car races were organized almost every year, local authorities tried to improve the roads before these events. Many dignitaries, generals, senior officials contributed to the allocation of financial and material resources for the construction of roads, as well as the solution of various organizational problems. The measures taken at the beginning of the 20th century by the government, zemstvos, commercial, industrial and financial circles made it possible to slightly increase the length of the road network, improve their condition, and introduce some technological innovations.

The revolutions of 1917 and the civil war of 1918-1920 had a huge impact on the development of the country's road network. During the Civil War, road construction was carried out by Voenstroy, Frontstroy, and the Highway Administration (Upshoss) of the NKPS. After the end of the civil war, countless reorganizations of these departments began. At the beginning of 1922, Upshoss and the Central Automobile Section of the Supreme Council of National Economy were merged and included in the Central Administration of Local Transport (TSUMT) as part of the NKPS. However, already in August 1922, by a joint decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR, the country's road infrastructure was divided between two departments - the TSUMT NKPS and the Main Directorate of Communal Services (GUKH) of the NKVD. The roads of national importance were under the jurisdiction of TSUMT, the direct concern for the condition of the roads was entrusted to the district departments of local transport (OMES) subordinate to TSUMT. Departments of communal services GUKH NKVD carried out the management of local roads.

The reforms of the road management authorities continued in subsequent years. At the same time, the state of the road remained in a deplorable state. The problem of financing road construction was particularly acute. At the same time, the country that carried out industrialization needed to create a developed transport system as soon as possible. The Soviet leadership tried to get out of this situation by transferring control of the roads of allied significance to the NKVD. In 1936, as part of the NKVD of the USSR, the Main Directorate of Highways (Gushosdor) was formed, which was in charge of roads of allied significance. As early as 1925, a natural road service was introduced in the country, according to which local residents were obliged to work for free a certain number of days a year on road construction. In 1936, a government decree was issued, which recognized the expediency of creating permanent local brigades, the work of which was included in the general plan for the labor participation of collective farmers. However, the main labor force in the construction of roads were prisoners. As a result of the second five-year plan (1933-1937), the country received more than 230 thousand kilometers of profiled dirt roads. At the same time, the plan for the construction of paved roads turned out to be underfulfilled by 15%.

A large road construction program was planned for the third five-year plan (1938–1942), but the Great Patriotic War prevented its implementation. During the war years, a significant part of the road equipment was transferred to the Red Army, many road workers went to the front. During the hostilities, 91,000 kilometers of roads, 90,000 bridges with a total length of 980 kilometers were destroyed, therefore, after the end of the war, the primary task facing the road services was the repair and restoration of roads. However, the fourth five-year plan, adopted in March 1946, poorly took into account the interests of the road industry, which was funded on a residual basis. At that time, two departments were responsible for the construction of roads - Gushosdor of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Main Road Administration (Glavdorupr). As part of Gushosdor in 1945, a Special Road Construction Corps was created, the basis of which was road troops.

In the 1950s, Gushosdor passed into the structure of the newly created Ministry of Automobile Transport and Highways of the USSR, where it was divided into two main departments - operational (Gushosdor) and construction (Glavdorstroy). All work on the construction of national roads, which was previously carried out by Gushosdor, was transferred to Glavdorstroy. Problems with the financing of the road industry were felt in these years as well. As before, attempts were made to involve the local population and the equipment of various enterprises in the road works. In 1950, Glavdorupr was simultaneously building 32 roads of republican significance and a number of local roads. The dispersal of resources and the multi-objective nature of tasks with poor material and personnel support had a negative impact on the results of the work.

http://www.rosavtodor.ru/doc/history/main15.jpg The peak of road construction in the USSR falls on the 60-70s. Significant funds are being allocated for road construction, and road builders are getting modern equipment. In 1962, the Moscow Ring Road was put into operation, with a length of 109 kilometers. In general, in the Russian Federation in 1959–1965, the length of paved roads increased by 81.2 thousand kilometers, 37 thousand kilometers of them had improved pavements. In the same years, the roads Kashira-Voronezh, Voronezh-Saratov, Voronezh-Shakhty, Saratov-Balashov, Vladimir-Ivanovo, Sverdlovsk-Chelyabinsk, and a number of others were built.

Intensive road construction continued in the 1970s and 1980s. As a result, in 1990 the network of public roads in the RSFSR amounted to 455.4 thousand kilometers, including 41 thousand kilometers of national roads and 57.6 thousand kilometers of republican significance.

However, in the early 1990s, about 167 district centers (out of 1837) were still not connected to regional and republican centers by paved roads. The residents of almost 1,700 central estates (out of 23,000) and about 250,000 medium and small settlements and farms did not have access to the main highway network on paved roads. Due to the difficult economic situation in the country, there was a big shortage of financial resources. At the same time, the transition to a market economy required a revision and fundamental change in the essence of many socio-economic categories, such as the form of ownership, planning, management of industrial relations, the psychology of the individual and society, and many other components of human existence.

Despite all the difficulties, for 1997-1999. there have been real shifts both in the development of the road network and in the efficiency of the functioning of the road sector. Over the past 12-13 years, Russia has seen an accelerated (up to 10% per year) growth in the car park, traffic intensity and road transport.

As of January 1, 2002, the length of motor roads in the Russian Federation was 904.7 thousand km, including 759.3 thousand km of paved roads and 145.4 thousand km of unpaved roads. The length of public roads is 588.7 thousand km, including 537.3 thousand km of paved roads (91%), unpaved roads - 51.4 thousand km. At the same time, the length of federal public roads is 46.6 thousand km, including 46.3 thousand km (99.3%) with a hard surface, and 542.1 thousand km of territorial public roads, in including hard-surfaced 491 thousand km (90%).

Yes, our roads are still inferior to European ones, and in general we do not have enough of them. Experts have calculated that in order to fully meet the socio-economic needs of the country, the minimum length of the Russian road network should be at least 1.5 million km, that is, increase one and a half times compared to what we already have.

Of course, this will require a significant increase in the volume of road construction. Here it is appropriate to quote the statement of Sergei Frank, Minister of Transport of the Russian Federation. He announced that the national program for the development of the road network envisages an increase in the total length of Russian roads by 2010 by 80,000 km. This task is supposed to be carried out with the involvement of private investors, who will have the opportunity to create a network of toll roads in our country.

However, those who are frightened by the very phrase "toll roads" can be reassured. Commercial highways will only be an alternative to the conventional road network. The appearance of toll roads will not change the quality of functioning of existing roads, and first of all, federal highways. The driver himself will decide whether to drive straight as an arrow and ideally flat road, for which you will have to pay, or use the free one, the quality of which has become familiar to us. This practice has long been accepted in many countries of the world. And, in my opinion, this is quite fair, as long as there are no excesses.

Conclusion

The road builders do not stop there and direct their main efforts to expanding not only the domestic, but also the international space. This is reflected in the federal target program "Modernization of the transport system of Russia (2002-2010)" being implemented today, namely in the part "Roads" (the program "Roads of Russia in the 21st century"), which is based on the principle of developing international and Russian transport corridors : Baltic-Center-South, Western border-Center-Ural, North-South, North-West-Ural, Western Siberia-Far East and others. They play a central role in solving transport problems related to the expansion of international, interstate and interregional transport, economic, political, and cultural ties.

Currently, with the support of the Government of the Russian Federation, active work is underway on a long-term program for the development of the national network of Russian highways until 2025. New tasks are set, the main directions are determined, priorities are identified with one goal - to make Russia a country of developed motorization and excellent roads. Let's hope that this most difficult task will be completed not only in the central part, but also in the northern part of Russia, in the Far East and in Siberia.

List of used literature

1. Roads of Moscow [Electronic resource]: http://about-roads.ru/auto/moscow-roads/

2. Roads of Russia: trouble or victory [Electronic resource]: http://about-roads.ru/auto/autoroad-rus/2/

3. Roads of Russia: history and modernity [Electronic resource]: http://www.rosavtodor.ru/doc/history/hystory1.htm

4. History of roads in Russia and the world [Electronic resource]: http://about-roads.ru/auto/road-history/

Napoleonic aggressive army. The victory of Russia is not an easy miracle, an expression of the inflexible will and boundless determination of all the peoples of Russia, who rose in 1812 to fight the Patriotic War in defense of the national independence of their homeland. The national liberation character of the war of 1812 also determined the specific forms of participation of the masses in the defense of their homeland, and in particular the creation ...

E.A. " Legal basis organization and activities of the general police of Russia (XVIII - early XX century)”. Krasnodar: Kuban State Agrarian University, 2003. - 200 p. 2.5. Kuritsin V.M. "History of the Russian Police". Brief historical outline and main documents. Tutorial. - M .: "SHIELD-M", 1998.-200 p. LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE WORK doc. - document...

And a respectable breadwinner - the village - this is how Russia appears to Solzhenitsyn at the beginning of the 20th century. These are the views and ideas of Solzhenitsyn that lie in the interpretation of his concept. He is guided by them, describing the history of pre-revolutionary Russia, the Russia of the Soviet period, and when he wrote his "overwhelming considerations" about the future of the country. Conclusion After the Crash Soviet Union have to...

Eagle". In 1700, a decree was issued on domestic mail, which at first operated only between Moscow and Voronezh. Only in 1719 was it ordered to carry mail "to all noble cities." Thus, by 1723 in Russia there were 4 post offices, which were in charge of the Germans.Soon, 7 postal stations in Finland were added to them.The length of postal routes in the middle of the 18th century ...

More from and also more from

Millennium Roadmap

How the transport system developed in Russia before the advent of rails and sleepers

It is known that Russian statehood arose precisely on the river routes - first of all, "From the Varangians to the Greeks", from ancient Novgorod to ancient Kyiv. On this topic: The technology of walking the Tatar-Mongol to Russia

"Novgorod. Pier, Konstantin Gorbatov

But it is usually forgotten that the rivers remained the main "roads" of Russia throughout the next thousand years, until the beginning of mass railway construction.

Road heritage of Genghis Khan

The first to move a noticeable number of people and cargo across Russia outside the river "roads" were the Mongols during their invasion. Transport technologies were also inherited from the Mongols of Moscow Russia - the system of "pits", "pit chase". "Yam" is the Mongolian "road", "way" distorted by the Muscovites. It was this thoughtful network of posts with trained interchangeable horses that made it possible to link the vast sparsely populated space of Eastern Europe into a single state.

Yamskoy Prikaz is a distant ancestor of the Ministry of Railways and Federal postal service- first mentioned in 1516. It is known that under the Grand Duke Ivan III, more than one and a half thousand new "pits" were established. In the XVII century, immediately after the end of the Troubles, long years The Yamskaya Prikaz was headed by the savior of Moscow, Prince Dmitry Pozharsky.

But the land roads of Muscovy performed mainly only administrative and postal functions - they moved people and information. Here they were at their best: according to the memoirs of the ambassador of the Holy Roman Empire, Sigismund Herberstein, his messenger covered a distance of 600 miles from Novgorod to Moscow in just 72 hours.

However, the situation with the movement of goods was quite different. Until the beginning of the 19th century, there was not a single verst of paved road in Russia. That is, two seasons out of four - in spring and autumn - there were no roads simply as such. A loaded wagon could move there only with heroic efforts and at a snail's pace. It's not just about mud, it's also about rising water levels. Most of the roads - in our concept of ordinary paths - went from ford to ford.

The situation was saved by the long Russian winter, when nature itself created a convenient snowy way - "winter road" and reliable ice "crossings" along the frozen rivers. Therefore, the overland movement of goods in Russia to the railways was adapted to this change of seasons. Every autumn in the cities there was an accumulation of goods and cargo, which, after the establishment of a snow cover, moved around the country in large convoys of tens, and sometimes hundreds of sledges. Winter frosts also contributed to natural storage perishable products- in any other season, with the storage and conservation technologies that were almost completely absent then, they would have rotted on a long journey.

"Sigismund Herberstein on the way to Russia", engraving by Augustin Hirschvogel. 1547

According to the memoirs and descriptions of Europeans of the 16th-17th centuries that have come down to us, several thousand sleighs with goods arrived in winter Moscow every day. The same meticulous Europeans calculated that transporting the same cargo on a sleigh was at least two times cheaper than transporting it on a cart. It was not only the difference in the condition of roads in winter and summer that played a role here. Wooden axles and cart wheels, their lubrication and operation were at that time a very complex and expensive technology. Much simpler sleds were devoid of these operational difficulties.

Shackled and postal tracts

For several centuries, land roads played a modest role in the movement of goods; it was not for nothing that they were called “postal routes”. The center and main node of these communications was the capital - Moscow.

It is no coincidence that even now the names of Moscow streets remind of the directions of the main roads: Tverskaya (to Tver), Dmitrovskaya (to Dmitrov), Smolenskaya (to Smolensk), Kaluga (to Kaluga), Ordynka (to the Horde, to the Tatars) and others. By the middle of the 18th century, the system of "postal routes" that intersected in Moscow had finally taken shape. The St. Petersburg Highway led to the new capital Russian Empire. The Lithuanian highway led to the West - from Moscow through Smolensk to Brest, with a length of 1064 versts. The Kyiv tract to the "mother of Russian cities" totaled 1295 versts. The Belgorod tract Moscow - Orel - Belgorod - Kharkov - Elizavetgrad - Dubossary, 1382 versts long, led to the borders of the Ottoman Empire.

They went to the North along the Arkhangelsk highway, to the south they led the Voronezh highway (Moscow - Voronezh - Don region - Mozdok) in 1723 versts and the Astrakhan highway (Moscow - Tambov - Tsaritsin - Kizlyar - Mozdok) in 1972 versts. By the beginning of the long Caucasian war, Mozdok was the main center of communications for the Russian army. It is noteworthy that it will be so even in our time, in the last two Chechen wars.

The Siberian Highway (Moscow - Murom - Kazan - Perm - Yekaterinburg) with a length of 1784 versts connected central Russia with the Urals and Siberia.

The road in the Urals is probably the first consciously designed and built road in the history of Russia.

We are talking about the so-called Babinovskaya road from Solikamsk to Verkhoturye - it connected the Volga basin with the Irtysh basin. It was “designed” by Artemy Safronovich Babinov on the instructions of Moscow. The route he opened in the Trans-Urals was several times shorter than the previous one, along which Yermak went to Siberia. Since 1595, forty peasants sent by Moscow had been building the road for two years. According to our concepts, it was only a minimally equipped trail, barely cleared in the forest, but by the standards of that time, it was quite a solid trail. In the documents of those years, Babinov was called so - "the leader of the Siberian road." In 1597, 50 residents of Uglich were the first to experience this road, accused in the case of the murder of Tsarevich Dmitry and exiled beyond the Urals to build the Pelym prison. In Russian history, they are considered the first exiles to Siberia.

Without hard coating

By the end of the 18th century, the length of the "postal routes" of the European part of Russia was 15 thousand miles. The road network became denser to the West, but to the east of the Moscow-Tula meridian, the density of roads dropped sharply, in places tending to zero. In fact, only one Moscow-Siberian tract with some branches led to the east from the Urals.

The road through the whole of Siberia began to be built in 1730, after the signing of the Kyakhta Treaty with China - systematic caravan trade with the then most populated and richest state in the world was considered as the most important source of income for the state treasury. In total, the Siberian tract (Moscow - Kazan - Perm - Yekaterinburg - Tyumen - Tomsk - Irkutsk) was built for more than a century, having completed its equipment in the middle of the 19th century, when it was time to think about the Trans-Siberian railway.

Until the beginning of the 19th century, there were no roads with a hard all-weather surface in Russia at all. The capital highway between Moscow and St. Petersburg was considered the best road. It began to be built by order of Peter I in 1712 and was completed only 34 years later. This road, 770 miles long, was built by a specially created Chancellery of State Roads according to the then advanced technology, but still they did not dare to make it stone.

The “Capital Trakt” was built in the so-called fascine method, when a foundation pit was dug along the entire route to a depth of a meter or two and fascines, bundles of rods were laid in it, pouring layers of fascines with earth. When these layers reached the level of the ground, a platform of logs was laid on them across the road, on which a shallow layer of sand was poured.

"Fashinnik" was somewhat more convenient and reliable than the usual trail. But even on it, a loaded cart went from the old capital to the new one for five whole weeks - and this is in the dry season, if there was no rain.

In accordance with the laws of the Russian Empire

the repair of roads and bridges was to be carried out by the peasants of the respective locality. And the "road duty", for which rural peasants were mobilized with their tools and horses, was considered among the people one of the most difficult and hated.

In sparsely populated regions, roads were built and repaired by soldiers.

As the Dutch envoy Deby wrote in April 1718: “Tver, Torzhok and Vyshny Volochek are littered with goods that will be transported to St. Petersburg by Lake Ladoga, because the carters refused to transport them by land due to the high cost of horse feed and the poor condition of the roads ... ".

A century later, in the middle of the 19th century, Lessl, a professor at the Stuttgart Polytechnic School, described Russian roads as follows: “Imagine, for example, in Russia a convoy of 20-30 carts, with a load of about 9 centners, one horse, following one after another. AT good weather The convoy moves without obstacles, but during prolonged rainy weather, the wheels of the wagons sink into the ground to the axles and the entire convoy stops for whole days in front of overflowing streams ... ".

The Volga flows into the Baltic Sea

For a significant part of the year, Russian roads buried in mud were liquid in the truest sense of the word. But the domestic market, although not the most developed in Europe, and active foreign trade annually required a massive flow of cargo. It was provided by completely different roads - numerous rivers and lakes of Russia. And since the era of Peter I, a developed system of artificial canals has been added to them.

The Siberian tract in the painting by Nikolai Dobrovolsky "Crossing the Angara", 1886

The main export goods of Russia since the 18th century - bread, hemp, Ural iron, timber - could not be massively transported across the country by horse-drawn transport. Here, a completely different carrying capacity was required, which only sea and river vessels could give.

The most common small barge on the Volga with a crew of several people took 3 thousand pounds of cargo - on the road this cargo took over a hundred carts, that is, it required at least a hundred horses and the same number of people. An ordinary boat on the Volkhov lifted a little more than 500 pounds of cargo, easily replacing twenty carts.

The scale of water transport in Russia is clearly shown, for example, by the following statistics that have come down to us: in the winter of 1810, due to early frosts on the Volga, Kama and Oka, 4288 ships froze into ice far from their ports (“wintered”, as they said then) 4288 ships. In terms of carrying capacity, this amount was equivalent to a quarter of a million carts. That is, river transport on all waterways of Russia replaced at least a million horse-drawn carts.

Already in the 18th century, the basis Russian economy was the production of iron and iron. The center of metallurgy was the Urals, which supplied its products for export. Mass transportation of metal could be provided exclusively by water transport. The barge, loaded with Ural iron, set sail in April and reached St. Petersburg by autumn, in one navigation. The path began in the tributaries of the Kama on the western slopes of the Urals. Further downstream, from Perm to the confluence of the Kama with the Volga, the most difficult segment of the journey began here - up to Rybinsk. The movement of river vessels against the current was provided by barge haulers. They dragged a cargo ship from Simbirsk to Rybinsk for one and a half to two months.

From Rybinsk, the Mariinsky water system began, with the help of small rivers and artificial canals, it connected the Volga basin with St. Petersburg through the White, Ladoga and Onega lakes. From the beginning of the 18th century to the end of the 19th century, St. Petersburg was not only the administrative capital, but also the largest economic center of the country - the largest port in Russia, through which the main flow of imports and exports went. Therefore, the city on the Neva with the Volga basin was connected by as many as three "water systems" conceived by Peter I.

It was he who began to form a new transport system of the country.

Peter I was the first to think over and begin to build a system of canals linking together all the great rivers of European Russia: this is the most important and now completely forgotten part of his reforms,

before which the country remained a loosely interconnected conglomerate of disparate feudal regions.

Already in 1709, the Vyshnevolotsk water system began to work, when the Tvertsa River, a tributary of the upper Volga, was connected by canals and locks with the Tsna River, along which there was already a continuous waterway through Lake Ilmen and Volkhov to Lake Ladoga and the Neva. So for the first time there was a unified transport system from the Urals and Persia to the countries of Western Europe.

Two years earlier, in 1707, the Ivanovsky Canal was built, connecting the upper reaches of the Oka River through its tributary Upa with the Don River - in fact, for the first time, the huge Volga river basin was combined with the Don basin, capable of linking trade and freight traffic from the Caspian to the Urals with the regions into a single system Black and Mediterranean seas.

The Ivanovo Canal was built for ten years by 35,000 driven peasants under the leadership of the German Colonel Brekel and the English engineer Peri. Since the beginning Northern war the captured Swedes also joined the fortress builders. But the British engineer made a mistake in the calculations: the studies and measurements were carried out in an extremely high year. ground water. Therefore, the Ivanovsky Canal, despite the 33 locks, initially experienced problems with filling with water. Already in the 20th century, Andrei Platonov would write about this drama a production novel from the era of Peter the Great - “Epifan Gateways”.

The canal that connected the Volga and Don basins, despite all Peter's ambitions, never became a busy economic route - not only because of technical miscalculations, but primarily because Russia still had a whole century before the conquest of the Black Sea basin.

The technical and economic fate of the canals connecting the Volga with St. Petersburg was more successful. The Vyshnevolotsk canal system, built for military purposes hastily over 6 years by six thousand peasants and Dutch engineers, was improved and brought to perfection by the Novgorod merchant Mikhail Serdyukov, who turned out to be a talented self-taught hydraulic engineer, at the end of the reign of Peter I. True, at the birth of this man, his name was Borono Silengen, he was a Mongol who, as a teenager, was captured by Russian Cossacks during one of the skirmishes on the border with the Chinese Empire.

The former Mongol, who became Russian Mikhail, having studied the practice of the Dutch, improved the locks and other canal structures, raised him throughput twice, reliably linking the newborn St. Petersburg with central Russia. Peter I, in joy, transferred the canal to Serdyukov in hereditary concession, and since then, for almost half a century, his family received 5 kopecks per sazhen of the length of each ship passing through the canals of the Vyshnevolotsk water system.

Burlaki against Napoleon

Throughout the 18th century, unhurried technical progress of river vessels was going on in Russia: if in the middle of the century a typical river barge on the Volga accepted an average of 80 tons of cargo, then at the beginning of the 19th century a barge of similar sizes already took 115 tons. If in the middle of the 18th century an average of 3 thousand ships passed to St. Petersburg through the Vyshnevolotsk water system, by the end of the century their number had doubled and, in addition, 2-3 thousand rafts with timber exported were added.

"Barge haulers on the Volga", Ilya Repin

The idea of technological progress was not alien to people from the government boards of St. Petersburg. So, in 1757, on the Volga, on the initiative of the capital of the empire, so-called machine ships appeared. These were not steamships, but ships moving by means of a gate rotated by bulls. The ships were designed to transport salt from Saratov to Nizhny Novgorod - each lifted 50 thousand pounds. However, these "machines" functioned for only 8 years - barge haulers turned out to be cheaper than bulls and primitive mechanisms.

At the end of the 18th century, it cost more than one and a half thousand rubles to carry a barge with bread from Rybinsk to St. Petersburg. Loading a barge cost 30-32 rubles, the state fee - 56 rubles, but the payment to pilots, barge haulers, konogons and waterways (that was the name of the technical specialists who serviced the canal locks) was already 1200-1300 rubles. According to the surviving statistics of 1792, the Moscow merchant Arkhip Pavlov turned out to be the largest river merchant - in that year he spent 29 baroques with wine and 105 with Perm salt from the Volga to St. Petersburg.

By the end of the 18th century, the economic development of Russia required the creation of new waterways and new land roads. Many projects appeared already under Catherine II, the aging empress issued appropriate decrees, for the implementation of which officials constantly did not find money. They were found only under Paul I, and the grandiose construction work was completed already in the reign of Alexander I.

So, in 1797-1805, the Berezinsky water system was built, connecting the Dnieper basin with the Western Bug and the Baltic with canals. This waterway was used to export Ukrainian agricultural products and Belarusian timber to Europe through the port of Riga.

Map of the Mariinsky, Tikhvin and Vyshnevolotsk water systems

In 1810 and 1811, literally on the eve of Napoleon's invasion, Russia received two additional canal systems - the Mariinsky and Tikhvinskaya - through which the country's increased cargo flow went from the Urals to the Baltic. The Tikhvin system became the shortest route from the Volga to St. Petersburg. It began at the site of the modern Rybinsk reservoir, passed along the tributaries of the Volga to the Tikhvin connecting canal, which led to the Syas River, which flows into Lake Ladoga, and the Neva River. Since even in our time Lake Ladoga is considered difficult for navigation, along the coast of Ladoga, completing the Tikhvin water system, there was a bypass canal built under Peter I and improved already under Alexander I.

The length of the entire Tikhvin system was 654 versts, 176 of which were sections that were filled with water only with the help of sophisticated lock technology. A total of 62 locks worked, of which two were auxiliary, which served to collect water in special tanks. The Tikhvin system consisted of 105 cargo piers.

Every year, 5-7 thousand ships and several thousand more rafts with timber passed through the Tikhvin system. All gateways of the system were served by only three hundred technicians and employees. But 25-30 thousand workers were engaged in piloting ships along the rivers and canals of the system. Taking into account the loaders at the piers, the Tikhvin water system alone required over 40 thousand permanent workers - huge numbers for those times.

In 1810, goods worth 105,703,536 rubles were delivered to St. Petersburg by river transport from all over Russia. 49 kop.

For comparison, about the same amount was the annual budget revenues of the Russian Empire at the beginning of the 19th century on the eve of the Napoleonic wars.

The Russian water transport system played its strategic role in the victory of 1812. Moscow was not a key communication hub in Russia, so it was more of a moral loss. The systems of the Volga-Baltic canals reliably connected St. Petersburg with the rest of the empire even at the height of the Napoleonic invasion: despite the war and a sharp drop in traffic in the summer of 1812, goods worth 3.7 million rubles came to the capital of Russia through the Mariinsky system, and 6 million through the Tikhvin .

BAM Russian tsars

Only the direct expenses of Russia for the war with Napoleon amounted to a fantastic amount at that time - more than 700 million rubles. Therefore, the construction of the first roads with a hard stone surface, begun in Russia under Alexander I, progressed with average speed 40 miles per year. However, by 1820 the Moscow-Petersburg all-weather highway was operational and for the first time regular passenger stagecoach traffic was organized along it. A large carriage for 8 passengers, thanks to interchangeable horses and a stone-paved highway, covered the distance from the old to the new capital in four days.

After 20 years, such highways and regular stagecoaches were already functioning between St. Petersburg, Riga and Warsaw.

The inclusion of a significant part of Poland into the borders of Russia required the construction of a new canal from the empire. In 1821, Prussia unilaterally imposed prohibitive customs duties on the transit of goods to the port of Danzig, blocking access to the sea for Polish and Lithuanian merchants who became subjects of Russia. In order to create a new transport corridor from the center of the Kingdom of Poland to the Russian ports in Courland, Alexander I approved the August Canal project a year before his death.

This new water system, which connected the Vistula and the Neman, took 15 years to build. The construction was slowed down by the Polish uprising of 1830, in which the first leader became an active participant. construction works colonel Prondzinsky, who had previously served in Napoleon's army as a military engineer and was amnestied during the creation of the Kingdom of Poland.

In addition to the Augustow Canal, which passed through the territory of Poland, Belarus and Lithuania, an indirect result of the Napoleonic invasion was another canal dug far in the north-east of Russia. The North Catherine Canal on the border of the Perm and Vologda provinces connected the basins of the Kama and the Northern Dvina. The canal was conceived under Catherine II, and its previously unhurried construction was forced during the war with Napoleon. The North Catherine Canal, even in the event that the enemy reached Nizhny Novgorod, made it possible to keep the connection between the Volga basin through the Kama and the port of Arkhangelsk. At that time it was the only canal in the world built by hand in the deep taiga forests. Created largely for purely "military" reasons, it never became economically viable, and was closed 20 years after construction was completed, thereby anticipating the history of BAM a century and a half later.

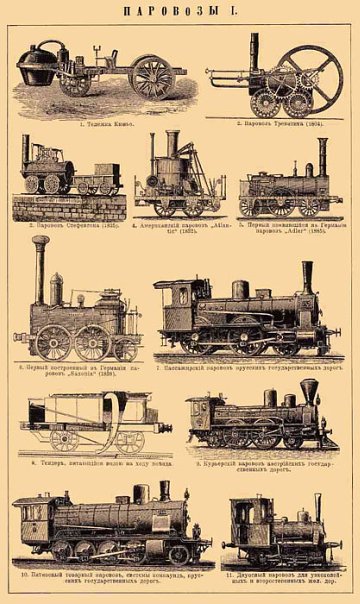

In the 60s - 80s of the XVIII century, first in England, and then in other countries, an industrial boom began. Instead of manual labor machine production appeared, instead of handicraft workshops and manufactories - large industrial enterprises. In 1763, the Russian engineer I. I. Polzunov presented steam engine project to supply air to melting furnaces. Polzunov's car had an amazing power for those times - 40 horsepower. revolutionized the industry steam machine, created by engineer James Watt in 1784. It is said that the idea of a steam engine came from Watt as a child, when he watched the bouncing lid of a boiling pot. It was one of the greatest inventions, thanks to which the powerful development of all fields of technology became possible. The versatility of Watt's steam engine made it possible to use it in any production and transport.

steam engine gave a powerful impetus to the development of transport. In 1769, the French artillery officer Joseph Cugno invented the first steam wagon to move heavy guns. True, it turned out to be so bulky and clumsy that during tests on the streets of Paris it broke through the wall of the house. This wagon has found its place in the Paris Museum of Arts and Crafts. William Murdoch decided to put Watt's engine on wheels. It is said that Watt himself was against it. Murdoch made a model of a steam wagon, but did not go beyond the model.

In 1802, the English designer Richard Trevithick made a steam car. The crew moved with a roar and fumes, frightening pedestrians. His speed reached 10 km/h. To get such a speed of movement, Trevithick made huge driving wheels, which were a good help on bad roads.  The birth of railways

The birth of railways

AT Ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome, there were track roads intended for the transport of heavy goods along them. They were arranged as follows: two parallel deep furrows passed along the road lined with stone, along which cart wheels rolled. In medieval mines, there were roads consisting of wooden rails along which wooden wagons were moved.

Around 1738, the rapidly deteriorating wooden mine roads were replaced by metal ones. In the beginning, they consisted of cast iron plates with grooves for the wheels, which was impractical and expensive. And in 1767, Richard Reynolds laid steel rails on the access roads to the mines and mines of Colbrookdale. Of course, they differed from modern ones: in cross section they had the shape latin letter U, the width of the rail was 11 cm, the length was 150 cm. The rails were sewn to wooden beam gutter up. With the transition to cast-iron rails, the wheels of the carts were also made of cast-iron. To move the trolleys along the rails, the muscular strength of a person or a horse was used.

Gradually, the rail tracks went beyond the mine yard. They began to be laid to the river or canal, where the cargo was transferred to ships and then moved by water. The problem of preventing derailment of wheels was solved. Corner iron was used, but this increased the friction of the wheels. Then they began to use the flanges at the wheels simultaneously with the mushroom-shaped shape of the rail in the section. The derailments have stopped.

In 1803, Trevithick decided to use his car to replace horse traction on railroad tracks. But Trevithick changed the design of the machine - he made a steam locomotive. On a biaxial frame with four wheels was a steam boiler with one steam pipe inside. A working cylinder was placed horizontally in the boiler above the steam pipe. The piston rod protruded far forward and was supported by a bracket.  The movement of the piston was transmitted to the wheels by means of a crank and gears. There was also a flywheel. This locomotive a short time worked on one of the mine roads. Cast iron rails quickly failed under the weight of the locomotive. Instead of replacing weak rails with stronger ones, they abandoned the steam locomotive. Already after Trevithick, forgetting about his invention, many tried to create a steam locomotive.

The movement of the piston was transmitted to the wheels by means of a crank and gears. There was also a flywheel. This locomotive a short time worked on one of the mine roads. Cast iron rails quickly failed under the weight of the locomotive. Instead of replacing weak rails with stronger ones, they abandoned the steam locomotive. Already after Trevithick, forgetting about his invention, many tried to create a steam locomotive.

The person who managed to analyze, generalize and take into account all previous experience in locomotive building was George Stephenson. Three types of Stephenson steam locomotive are known. The first one, named by him "Blucher", was built in 1814. The locomotive could move eight wagons weighing 30 tons at a speed of 6 km/h. The locomotive had two cylinders, a gear-wheel drive. Steam was escaping from the cylinders. Then Stephenson created a device that was a milestone in locomotive construction - a cone. The exhaust steam was discharged into the chimney.

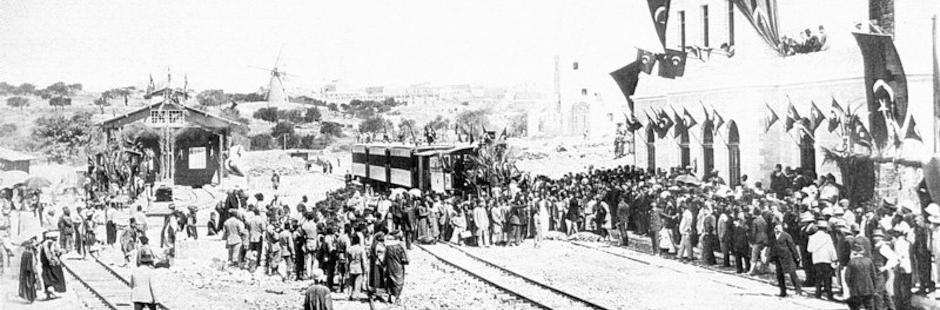

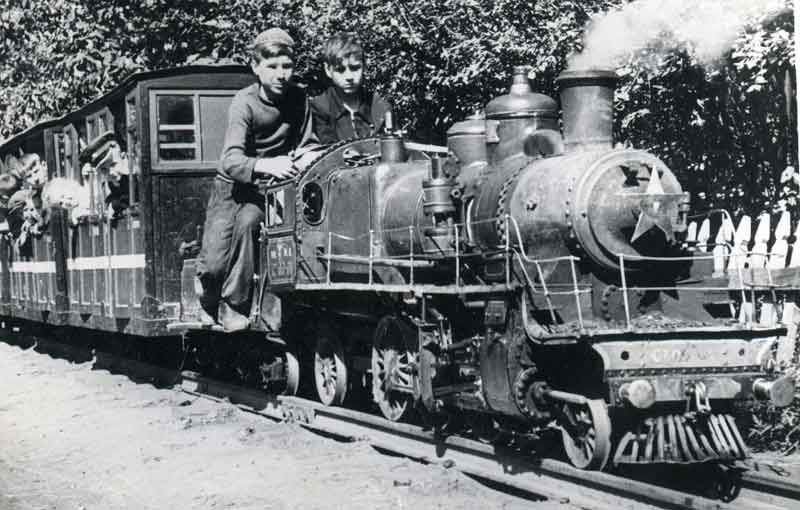

The second steam locomotive was created in 1815. Stephenson replaced the gear train with a direct crank mechanism connecting the pistons of the cylinders to the moving axles and paired the wheels with rigid drawbars. Stephenson was the first locomotive builder to pay attention to the track and to the interaction of locomotive and track. He changed the connection of the rails, softening the shocks, and supplied the locomotive with suspension springs. Stephenson came to the conclusion that the path should be as horizontal as possible and that, despite the high cost track works, it is necessary to install embankments and excavations during construction railway. On the world's first railway line, Stockton - Darlington, horses were supposed to be used as traction as the most reliable means. In 1823 Stephenson began working on the construction of this line, and in the same year he established the world's first locomotive works in Newcastle. The first steam locomotive that came out of this plant was called Lokomashen No I. It differed little from the previous ones and transported goods at a speed of 18-25 km / h. Horses were used to move passenger cars on the Stockton - Darlington line. On the steepest sections, the trains moved with the help of ropes. Both cast iron and steel rails were laid.  The first steam railway from Liverpool to Manchester opened in 1830.. Since that time, the rapid development of rail transport began. In the same 1830, the first railroad was built in America between Charleston and Augusta, 64 km long. Steam locomotives were brought here from England. Then the railway construction began one after another European countries:

The first steam railway from Liverpool to Manchester opened in 1830.. Since that time, the rapid development of rail transport began. In the same 1830, the first railroad was built in America between Charleston and Augusta, 64 km long. Steam locomotives were brought here from England. Then the railway construction began one after another European countries:

1832-1833 - France, Saint-Etienne-Lyon, 58 km;

1835 - Germany, Furth - Nuremberg, 7 km;

1835 - Belgium, Brussels-Meheln, 21 km;

1837 - Russia, St. Petersburg-Tsarskoye Selo, 26.7 km.