China and the Mongols - the history of relations. Genghis Khan

Mongols conquer China

In the XII century. four states coexisted on the territory of modern China, in the north - the Jurchen Empire of Jin, in the northwest - the Tangut state of Western Xia, in the south - the South Sung Empire and the state formation of Nanzhao (Dali) in Yunnan.

This balance of power was the result of foreign invasions of nomadic tribes who settled on Chinese lands. There was no longer a single China. Moreover, when at the beginning of the 13th century. the danger of a Mongol conquest loomed over the country, each of the states turned out to be extremely weakened by internal turmoil and was unable to defend its independence. At the northern borders of China, tribes consisting of Tatars, Tai-Chiuts, Kereits, Naimans, Merkits, later known as the Mongols, appeared at the beginning of the 13th century As early as the middle of the 12th century, they roamed the territory of the modern Mongolian People's Republic, in the upper reaches of the river. Heilongjiang and in the steppes surrounding Lake Baikal.

The natural conditions of the habitats of the Mongols led to the occupation of nomadic cattle breeding, which emerged from the primitive complex of agricultural-cattle-breeding-hunting. In search of pastures rich in grass and water, suitable for grazing cattle and small cattle, as well as horses, the Mongol Tribes roamed the vast expanses of the Great Steppe. Domestic animals supplied the nomads with food. Felt was made from wool - a building material for yurts, shoes and household items were made from leather. Handicraft products were used for domestic consumption, while livestock was exchanged for agricultural products and urban crafts of settled neighbors necessary for nomads. The significance of this trade was all the more significant, the more diversified the nomadic pastoralism became. The development of Mongolian society was largely stimulated by ties with China. So, it was from there that iron products penetrated into the Mongolian steppes. The experience of blacksmithing of Chinese masters, used by the Mongols to make weapons, was used by them in the struggle for pastures and slaves. The central figure of Mongolian society was personally free arats. Under the conditions of extensive nomadic pastoralism, these ordinary nomads grazed cattle, sheared sheep, and made traditional carpets, which are necessary in every yurt. In their economy, the labor of prisoners of war converted into slavery was sometimes used.

In the nomadic society of the Mongols, a significant transformation took place over time. Initially, the traditions of the tribal community were sacredly observed. So, for example, during the constant nomadic life, the entire population of the clan in the camps was located in a circle around the yurt of the tribal elder, thereby constituting a kind of camp-kuren. It was this tradition of the spatial organization of society that helped to survive in difficult, sometimes life-threatening steppe conditions, when the nomad community was still underdeveloped and needed the constant cooperation of all its members. Starting from the end of the XII century. with the growth of property inequality, the Mongols began to roam the villages, i.e. small family groups connected by ties of consanguinity. With the decomposition of the clan in the course of a long struggle for power, the first tribal unions were formed, headed by hereditary rulers who expressed the will of the tribal nobility - noyons, people of the "white bone".

Among the heads of clans, Yesugei-Batur (from the Borjigin clan), who wandered in the steppe expanses to the east and north of Ulaanbaatar, and became the leader-kagan of a powerful clan - a tribal association, especially exalted. Yesugei-batur was succeeded by his son Temujin. Having inherited the warlike character of his father, he gradually subjugated the lands in the West - to the Altai Range and in the East - to the upper Heilongjiang, uniting almost the entire territory of modern Mongolia. In 1203, he managed to defeat his political rivals - Khan Jamu-khu, and then over Wang Khan.

In 1206, at the congress of noyons - kurultai - Temuchin was proclaimed the all-Mongolian ruler under the name of Genghis Khan (c. 1155-1227). He called his state Mongolian and immediately began aggressive campaigns. The so-called Yasa of Genghis Khan was adopted, which legitimized aggressive wars as a way of life for the Mongols. In this occupation, which became everyday for them, the central role was assigned to the cavalry, hardened by constant nomadic life.

The pronounced military way of life of the Mongols gave rise to a peculiar institution of nukerism - armed warriors in the service of the noyons, recruited mainly from tribal nobility. From these ancestral squads, the armed forces of the Mongols were created, sealed by blood ancestral ties and headed by leaders tested in long exhausting campaigns. In addition, the conquered peoples often joined the troops, strengthening the power of the Mongol army.

Wars of conquest began with the invasion of the Mongols in 1209 on the state of Western Xia. The Tanguts were forced not only to recognize themselves as vassals of Genghis Khan, but also to take the side of the Mongols in the struggle against the Jurchen Jin Empire. Under these conditions, the South Sung government also went over to the side of Genghis Khan: trying to take advantage of the situation, it stopped paying tribute to the Jurchens and concluded an agreement with Genghis Khan. Meanwhile, the Mongols began to actively establish their power over Northern China. In 1210 they invaded the state of Jin (in the Shanxi province).

At the end of the XII - beginning of the XIII century. The Jin Empire underwent great changes. Part of the Jurchens began to lead a settled way of life and engage in agriculture. The process of disengagement in the Jurchen ethnos sharply aggravated the contradictions within it. The loss of monolithic unity and former combat capability became one of the reasons for the defeat of the Jurchens in the war with the Mongols. In 1215, Genghis Khan captured Beijing after a long siege. His commanders led their troops to Shandong. Then part of the troops moved to the northeast in the direction of Korea. But the main forces of the Mongol army returned to their homeland, from where in 1218 they began a campaign to the West. In 1218, having captured the former lands of the Western Liao, the Mongols reached the borders of the Khorezm state in Central Asia.

In 1217, Genghis Khan again attacked the Western Xia, and then eight years later launched a decisive offensive against the Tanguts, inflicting a bloody pogrom on them. The conquest of the Western Xia by the Mongols ended in 1227. The Tanguts were slaughtered almost without exception. Genghis Khan himself participated in their destruction. Returning home from this campaign, Genghis Khan died. The Mongolian state was temporarily headed by his youngest son Tului.

In 1229, the third son of Genghis Khan, Ogedei, was proclaimed the great khan. The capital of the empire was Karakorum (southwest of present-day Ulaanbaatar).

Then the Mongol cavalry headed south of the Great Wall of China, seizing the lands that remained under the rule of the Jurchens. It was at this difficult time for the Jin states that Ogedei concluded an anti-Jurchen military alliance with the Southern Sung emperor, promising him the lands of Henan. Going to this alliance, the Chinese government hoped with the help of the Mongols to defeat the old enemies - the Jurchens and return the lands they had seized. However, these hopes were not destined to come true.

The war in Northern China continued until 1234 and ended with the complete defeat of the Jurchen kingdom. The country was terribly devastated. Having barely ended the war with the Jurchens, the Mongol khans unleashed hostilities against the southern Sungs, terminating the treaty with them. A fierce war began, which lasted for about a century. When the Mongol troops invaded the Sung Empire in 1235, they met with a fierce rebuff from the population. The besieged cities stubbornly defended themselves. In 1251, it was decided to send a large army to China, led by Khubilai. The great Khan Mongke, who died in Sichuan, took part in one of the campaigns.

Beginning in 1257, the Mongols attacked the South Sung Empire from different sides, especially after their troops marched to the Dai Viet borders and subjugated Tibet and the state of Nanzhao. However, the Mongols managed to occupy the southern Chinese capital of Hangzhou only in 1276. But even after that, detachments of Chinese volunteers continued to fight. Fierce resistance to the invaders was provided, in particular, by the army led by a major dignitary Wen Tianxiang (1236-1282).

After a long defense in Jiangxi in 1276, Wen Tianxiang was defeated and taken prisoner. He preferred the death penalty to serving Khubilai. Patriotic poems and songs, created by him in prison, were widely known. In 1280, in battles at sea, the Mongols defeated the remnants of the Chinese troops.

China under the rule of the Mongol EmpireDespite long and staunch resistance, for the first time in its history, all of China was under the rule of foreign conquerors. Moreover, it became part of the gigantic Mongol Empire, which covered the territories adjacent to China and stretched all the way to Western Asia and the Dnieper steppes.

Claiming the universal and even universal nature of their state, the Mongol rulers gave it the Chinese name Yuan, meaning "the original creation of the world." Breaking with their nomadic past, the Mongols moved their capital from Karakorum to Beijing.

The new government faced the difficult task of establishing itself on the throne in a country of ancient culture alien to the Mongols, which for centuries had been creating the experience of state building in the conditions of an agricultural civilization.

The Mongols, who conquered their great neighbor with fire and sword, acquired a heavy inheritance. The former Middle Empire, and especially its northern part, experienced a deep decline caused by the disastrous consequences of the invasion of nomads. The very development of once prosperous China was reversed.

According to the sources of that time, in the mid-30s of the XIII century. the population in the north has decreased by more than 10 times compared with the beginning of the century. Even by the end of the Mongol invasion, the population of the south outnumbered the northerners by more than four times.

The country's economy went into decline. The fields were deserted and the cities deserted. Slave labor became widespread.

Under these conditions, the ruling circles of the Yuan Empire inevitably faced the question of a strategy for relations with the conquered Chinese ethnos.

The gap in cultural traditions was so great that the first natural impulse of the Mongols shamanists was to turn the incomprehensible world of a settled civilization into a huge pasture for cattle. However, by the will of fate, the victors, plunged into the attractive cultural field of the defeated, soon chose to abandon their original plans for the almost total extermination of the population of the conquered territory. Genghis Khan's adviser, a Khitan by origin, Yelü Chutsai, and then Kublai's Chinese assistants convinced the emperors of the Yuan dynasty that traditional Chinese methods of governing subjects could bring significant benefits to the khan's court. And the conquerors began to learn with interest all the ways known in China to streamline relations with various categories of the population.

However, the Mongolian elite had to study for a long time. The political climate of the Yuan Empire was influenced by two leading trends that were becoming increasingly apparent. The desire to assimilate the vital experience of Chinese politicians was hampered by distrust of their subjects, whose way of life and spiritual values were initially incomprehensible to the Mongols. All their efforts were aimed at not dissolving into the mass of the Chinese, and the main dominant policy of the Yuan rulers was the policy of asserting the privileges of the Mongolian ethnic group.

Yuan legislation divided all subjects into four categories according to ethnic and religious principles.

The first group consisted of the Mongols, in charge of which the leadership of almost the entire administrative apparatus and the command of the troops was concentrated. The Mongolian elite literally controlled the life and death of the entire population. The Mongols were joined by the so-called "semu jen" - "people of different races" - foreigners, who make up the second category. In the course of their conquests, the Mongols entered into voluntary or forced contact with various peoples of the world. They were quite tolerant of all religions and were open to a variety of external influences. Appealing to people from different countries, apparently, allowed the new rulers to more easily keep the numerous Hans in line, following the principle of "divide and rule." It was during the Mongol period that people from Central Asia, Persia, and even Europeans were recruited in China.

Suffice it to mention that 5,000 European Christians settled in Beijing. In 1294, the Pope's ambassador, monk Giovanni Monte Corvino, was at the Yuan court until the end of his life, and in 1318-1328. The Italian traveler-missionary Odarico di Pardenone (1286-1331) lived in China. The Venetian merchant Marco Polo (c. 1254-1324) was especially famous. He arrived in the Far East with trading purposes and for a long time held a high position under Kublai. The Chinese political elite was removed from the helm of government. So, the Uzbek Ahmed was in charge of finances, Nasper Addal and Masargiya served as military leaders. Although, compared with the Mongols, foreigners occupied a lower position in the social structure of society, they, like representatives of the dominant ethnic group, enjoyed special protection from the authorities and had their own courts.

The lowest, fourth, category of the free population were the inhabitants of the South of China (nan jen).

The original population of the Middle Empire was subjected to all sorts of restrictions. People were forbidden to appear on the streets of the city at night, arrange any gatherings, learn foreign languages, and learn the art of war. At the same time, the very fact of dividing a single Han ethnic group into northerners and southerners pursued the goal of driving a wedge between them and thereby strengthening their power as invaders.

Concerned primarily with streamlining relations with the Chinese majority, the Mongols adopted the Chinese model of social development, in particular the traditional ideas about the essence of the emperor's power as the bearer of all management functions in a single person: political, administrative, legal.

Created in this regard, a special group of departments consisted of 15 institutions serving the needs of the imperial court and the capital.

The main administrative body of the Mongols was the traditional imperial council - the cabinet of ministers with six departments under it, dating back to the Sui time. A powerful means of combating centrifugal tendencies in the country was the censorship, which was originally used in China to supervise officials.

But the basis of the power of the Mongols was their advantage in the military field: they secured leading positions in the management of military affairs (Shumiyuan) and in the main military department of weapons.

Contrary to popular belief about the high degree of centralization of the Yuan Empire, the functions of the government administration, the administration of appanages and other territories extended mainly to the capital province. To make up for the lack of lower-level administration outside the Yuan home, control centers were created there, to which officials from the center were sent, endowed with enormous powers. Although the government proclaimed its authority over local structures, it failed to achieve full administrative and political control.

Under the control of the central government, in essence, there was only the capital - the city of Dadu (modern Beijing) and the northeastern limits of the Yuan state adjoining the metropolitan area. The rest of the territory was divided into eight provinces.

The gradual familiarization of the Mongolian elite with Chinese culture was manifested in the restoration of the traditional Chinese institution of examinations, which is closely connected with the functioning of the administrative apparatus and the education system. These components traditionally provided personnel for all government bodies and determined the culture and way of life of the Han ethnic group. It is significant that as early as 1237, before the establishment of the Yuan dynasty, under Ugedei, on the advice of Yelü Chucai, an attempt was made to revive the examination system. It is curious that even Confucians who were taken prisoner and became slaves were included in the trials, and their masters were punished by death if they hid the slaves and did not send them to the exams.

As the power of the Mongol khans over China stabilized and consolidated and the need for new areas of government and administrative apparatus arose in this regard, the process of their partial restoration began.

However, the nature of communication between the bearers of the two cultures did not always develop smoothly. There were several aspects to this. The relations of the Mongolian authorities with the Chinese scribes in the south, who received a traditional education and academic title back in the Sung time, were especially difficult. The accession of the Yuan dynasty was marked by the abolition of the institute of examinations, and therefore the bureaucratic machine created by the Mongols before the conquest of South Sung China turned out to be filled with Northern Chinese and representatives of other nationalities. Under these conditions, southern scribes, removed from service, were in demand mainly in the education system.

In an attempt to win over Chinese intellectuals and extinguish anti-Mongolian sentiments among them, the Yuan authorities in 1291 issued a decree on the establishment of public schools and academies (shuuan), which determined the principles for recruiting their personnel and their promotion through the ranks.

The academies, which were educational institutions of a higher level and less dependent on the authorities, retained their positions under the Mongol dynasty. The Academy played the role of a collector and custodian of books, and often their publisher. These educational institutions became a haven for many Southern Sung scholars who used their knowledge here and did not want to be in the service of the Yuan court.

On the other hand, any advancement of the Mongol rulers along the path of familiarization with Chinese culture met with opposition in the Mongol environment itself. During the reign of Khubilai - the last great khan and the first emperor of the Yuan Dynasty - the question of introducing an examination system as a means of selecting officials and an incentive for acquiring knowledge arose several times. But attempts to introduce a new system of selection of officials through examinations caused discontent and resistance from the Mongol nobility, who feared a departure from the tribal order. How strong this opposition was is shown by the fact that the decree promulgated in 1291 under Khubilai, which allowed the Chinese to occupy any position below the governor of the province, was not enforced under his successors.

Only Ren Zong (1312-1320), an adherent of Confucianism, who issued a decree on examinations in 1313, managed to overcome the obstacles to the restoration of the examination system, including breaking the resistance of the Mongol nobility. Beginning in 1315, examinations were held regularly every three years until the end of the Yuan Dynasty.

For the Mongols and foreigners, a different program was envisaged than for the Chinese. This was explained not only by the discrimination of the latter, but also by the poorer training of the former. The Mongols found it difficult to get used to their unusual cultural environment and political traditions. At the same time, many of the former steppe nomads were becoming Chinese-educated people and could compete, albeit on favorable terms, with sophisticated Chinese scribes.

In addition to general examinations related to the study and interpretation of Confucian canons, some special examinations were also introduced. So, a lot of attention was paid to exams in medicine. Constant wars created an increased need for medical care, and therefore the Mongols sought to use ancient Chinese medicine for their own benefit.

In the policy of the Mongolian rulers in the field of state building and education, and in particular in relation to the Chinese institute of examinations, the confrontation between the Chinese and the Mongolian principles, the ways of life of the two ethnic groups, the culture of farmers and nomads, was especially clearly reflected, which actually did not stop during the entire Yuan period. Under the conditions of the initial defeat of Chinese culture, a tendency towards a noticeable restoration and even triumph of its positions was increasingly revealed. Indicative, in particular, is the establishment of Mongolian schools on the Chinese model and the teaching of Mongolian youth in them on Chinese classic books, although translated into the Mongolian language.

Another very important side of the beneficial influence of Chinese culture was historical writing.

Trying to present themselves as legitimate rulers - heirs of the previous Chinese dynasties, the Mongols paid much attention to compiling official dynastic histories. Thus, under their patronage, after several years of preparatory work, the histories of the Liao (907-1125), Jin (1115-1234) and Song (960-1279) dynasties were compiled in just three years. Thus, the conquerors sought to take into account the mood of the indigenous population and especially its cultural traditions, and thereby contribute to the political consolidation of their power. A significant step in this direction was the creation in the early 60s. 12th century Guoshiyuan Historiographic Committee, designed to preserve and compile historical records and documents. Thus, a tradition dating back to the Han period was restored. Subsequently, Guoshiyuan was merged with the Hanlin Confucian Academy in order to write not only the above-mentioned Chinese histories, but also to compile chronicles of the reign of the Mongol emperors in Mongolian and Chinese.

Historiographical work on dynastic histories became a sphere of ideological struggle. One of the main issues of discussion was the question of the legitimacy of the non-Chinese Liao and Jin dynasties, which meant that the legitimacy of the existing Mongol dynasty was also questioned.

Summing up the cultural borrowings of the Mongolian elite, we can say that their policy, especially in the field of education, was a kind of compromise, a concession to the upper strata of the conquered ethnic group on the part of the Mongolian ruling stratum, forced to do this due to the country's need for officials (both Mongolian and Chinese), due to the weakening of the Mongol power over China and a certain Chineseization of the Mongol court and nobility. The defeated ethnos, as the bearer of the ancient cultural substratum and rooted political tradition, gradually triumphed over the forms of traditional institutions introduced by the Mongols.

In connection with the conscious policy of dividing subjects into different strata, the socio-economic policy of the state was also built, and above all in the agrarian area.

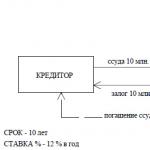

In the context of the disorganization of the country's economy, the Mongol rulers made a turn towards streamlining the administration of subject territories. Instead of unsystematic predatory extortions, they switched to fixing taxation: a tax administration was created in the provinces, population censuses were carried out.

The Mongolian nobility disposed of the lands in Northern and Central China. The Mongol rulers received a significant part of their financial income from specific possessions. The new owners distributed arable fields, lands, entire villages of the Mongol nobility to foreigners and Chinese who entered their service, to Buddhist monasteries. The institution of official lands was restored, feeding the privileged part of society from among the educated elite.

In the south of the Yuan Empire, most of the land remained with the Chinese owners with the right to buy and sell and transfer by inheritance. In the South, taxes were heavier than in the North.

The policy of the conquerors contributed to the ruin of weak farms and the seizure of land and peasants by monasteries and influential families.

During the conquest of China by the Mongols, the original population found itself in the position of slaves, whose labor in agriculture and the household, in craft workshops, was actually slave labor. The share of tenants of private land - dianhu and kehu, who suffered from unfixed taxes, turned out to be a little easier. They gave most of the harvest to the owners of the land - Mongolian and Chinese officials, and Buddhist monasteries.

Guild craftsmen were subject to heavy requisitions. Often they were forced to additionally give away part of the goods, to work for free for the garrison.

Merchants and their organizations were also heavily taxed and paid numerous duties. Chinese merchants needed special permission to transport goods.

The financial policy of the Mongolian authorities worsened the situation of all segments of the population. Relations with the Chinese elite of society also sharply worsened. The Chinese who served Khubilai, dissatisfied with his rule, revolted. In 1282, in the absence of the khan, the all-powerful Ahmed was killed in the capital. Foreigners gradually began to leave the country.

The rulers of the Yuan dynasty - the successors of Khubilai - were eventually forced to cooperate with the ruling class of China and fill the institutions with Han officials.

Khubilai, continuing his wars with the southern Chinese, threw his forces to the east. In 1274, and then in 1281, he equipped naval expeditions to conquer Japan. But the ships of his flotilla died from the storm, never reaching the Japanese islands. Then the conquering aspirations of the Yuan emperor turned to the south. Back in the 50s. 13th century Khubilai's troops invaded Dai Viet, where they met with a decisive rebuff. In the 80s. Khan again made attempts to conquer the country, but a fierce guerrilla war began there. The Chinese fleet, sent by the Mongols to the south to conquer the ports, was sunk in the Red River Delta. The Mongolian commanders withdrew the remnants of their troops to the north. In 1289 diplomatic relations between the two countries were restored.

Khubilai's successors, who ruled in Beijing, continued their active foreign policy for some time. In the 90s. 13th century they undertook a naval expedition to about. Java. With the weakening of the empire's military power, the Yuan emperors abandoned conquest.

The overthrow of the Mongol yokeBy the middle of the XIV century. The Yuan Empire fell into complete decline. The policy of the authorities had a destructive effect on the life of the city and village of Northern China. In addition, natural disasters erupted - river floods, changes in the course of the Yellow River, flooding of vast plains - reduced the area under crops and led to the ruin of farmers. City markets were empty, workshops and artisan shops were closed.

The treasury compensated for the reduction in in-kind receipts by issuing new paper money, which in turn led to the bankruptcy of artisans, trading companies and usurers.

The situation in the country is extremely tense. The Yuan authorities, fearing a massive explosion, forbade the people from keeping weapons. At the court, a project was even developed to exterminate a large part of the Chinese - the owners of the five most common surnames in the country.

In the 30s. 14th century peasants everywhere took up arms. They were supported by the townspeople and peoples of the South. In songs, popular stories of wandering storytellers, invincible heroes, brave generals, brave strongmen and just men of the past were sung. Theatrical performances were played on these themes. It was then that the novel "Three Kingdoms" appeared, which glorified the glorious past of the Chinese ethnos, and above all military prowess, the extraordinary skill of ancient Chinese military leaders. Scientists-astrologers reported ominous heavenly signs, and fortune-tellers predicted the end of the power of foreigners.

Among the secret religious teachings of various persuasions and directions, the messianic idea of the coming of the "Buddha of the future" - Maitreya (Milefo) - and the beginning of a new happy era, as well as the doctrine of the light of the Manichaean persuasion, was especially popular. The secret Buddhist "White Lotus Society" called for a fight against the invaders and formed "red troops" (red is the symbol of Maitreya).

In 1351, when the authorities drove thousands of peasants to build dams on the Huang He, the uprising took on a mass character. He was joined by farmers, salt workers, city dwellers, small merchants, representatives of the lower classes of the ruling class. The movement was aimed at overthrowing the foreign yoke and the power of the Yuan dynasty.

The "White Lotus Society" put forward the idea of recreating the Chinese state and restoring the power of the Song Dynasty. One of the leaders of the rebels, Han Shantong, being declared a descendant of the once reigning house, was proclaimed the Sung emperor. The leadership of military operations was taken over by one of the leaders of the secret brotherhood, Liu Futong. The leaders of the uprising denounced the Mongol rulers, claiming that "meanness and flattery" are in power in the country, that "thieves have become officials, and officials - thieves."

The uprising of the "Red troops" covered almost the entire north of the country. The rebels occupied Kaifeng, Datong and other major cities, reached the Great Wall of China, approached the capital. The government troops were defeated.

In 1351, uprisings swept through the central regions of China, where the coming of Maitreya was also preached. In this economically developed region of the country, townspeople played a significant role in the movement along with the peasants. The rebels acted against the Yuan authorities and large local landowners, made successful campaigns along the Yangtze Valley in the provinces of Zhets-jiang, Jiangxi and Hubei. In Anhui, the rebels were led by Guo Jiaxing. In 1355 after the death of Guo Jiaxing, Zhu Yuanzhang, the son of a peasant, a wandering monk, took over command of the army.

The rebels of this province were associated with the movement of the "Red troops" and recognized the pretender to the throne of the Sung. The Mongolian nobility created military detachments, appointed representatives of the Chinese nobility to high posts, sent opposing imperial troops against the rebels. Detachments of the "Red troops" suffered serious losses. In 1363, the main forces of Liu Futong were defeated, and he himself was killed. Part of the detachments of the "red troops" withdrew through Shaanxi to Sichuan, part joined Zhu Yuanzhang.

The anti-Mongolian movement in Central China continued to grow stronger. Zhu Yuanzhang settled in Nanjing. Since the Chinese officials in this region did not support the power of the Yuan (as it was in the North), he appointed many of them as advisers.

Having defeated his rivals, Zhu Yuanzhang sent an army to the north and in 1368 occupied Beijing. The last of the descendants of Genghis Khan ruling in China fled to the north. Zhu Yuanzhang, proclaimed emperor of the new Ming Dynasty in Nanjing, conquered the country's territories for about 20 more years.

Genghis Khan. The beginning of the conquest of China

Upon fulfilling the task of uniting the Mongolian peoples inhabiting the plateau of Central Asia into one State, the eyes of Genghis Khan naturally turned to the East, to the rich, cultured, populated by a non-belligerent people of China, which has always been a tidbit in the eyes of nomads. The lands of China proper were divided into two states - the Northern Jin (Golden Kingdom) and the Southern Song, both of Chinese nationality and Chinese culture, but the second with a national dynasty at the head, while the first was ruled by a foreign dynasty of conquerors - the Jurchens. The first object of Genghis Khan's actions, of course, was the closest neighbor - the Jin state, with which he, as the heir to the Mongol khans of the 11th and 12th centuries, had his own long-standing accounts.

In fact, none other than the Jin emperor destroyed - and not so much with the help of military force, but with his insidious policy - the strong Mongol state that was emerging under the khans of Khabul and Khatul, inciting envious and greedy nomad neighbors against it. One of the Mongol khans, Ambagai, was taken prisoner and tortured by the Jin. The Mongols remembered all this well and deeply harbored a thirst for revenge in their hearts, only waiting for an opportunity to give this feeling an outlet. Naturally, the newly born national hero, the invincible Genghis Khan, should have been the spokesman for such people's aspirations.

However, as a man who equally possessed both military and political genius, the Mongol Autocrat perfectly understood that the war with China was not such an enterprise that one could embark on headlong; on the contrary, he knew that it was necessary to carefully and comprehensively prepare for it. The first step already taken in this direction was the merger of the nomadic tribes of Central Asia into one power with a strong military and civil organization. In order to lull the vigilance and suspicion of his enemy, Genghis Khan during this period of accumulation of strength refrains from everything that could be interpreted as hostile intentions, and for the time being does not refuse to recognize himself as a nominal tributary of the Jin Emperor.

Such peaceful relations contribute to the establishment of trade and other ties between the Mongol and Jin states, and Genghis Khan uses these relations with amazing skill to carefully and comprehensively study the future enemy. This enemy is strong: he has an army that far outnumbers those forces that can be put up against it by Genghis Khan, an army well trained and technically equipped, based on many dozens of strong cities and led by leaders well educated in their specialty.

In order to fight it with the hope of success, it is necessary to put at least all the armed forces of the Mongolian state against it, leaving its northern, western and southern borders without troops. So that this does not pose a danger, it is necessary to first protect them from possible attempts by other neighbors during the entire period while the Mongol army is busy fighting its eastern enemy, in other words, it is necessary to ensure its rear in the broad sense of the word. To this end, Genghis Khan undertook a number of campaigns that have no independent significance, but serve as preparation for the Chinese campaign.

The main object of secondary operations is the Tangut state, which occupied vast lands in the upper and part of the middle reaches of the Yellow River, which managed to join Chinese culture, and therefore became rich and fairly well organized. In 1207, the first raid was made on it; when it turns out that this is not enough to completely neutralize it, a campaign is undertaken against it on a larger scale.

This campaign, completed in 1209, gives Genghis Khan a complete victory and huge booty. It also serves as a good school for the Mongolian troops before the upcoming campaign against China, since the Tangut troops were partly trained in the Chinese system. By obliging the Tangut ruler to pay an annual tribute and weakening it so that over the next few years it was possible not to fear any serious hostile actions, Genghis Khan can finally begin to realize his cherished dream in the east, since by the same time security has been achieved and on the western and northern borders of the Empire. It happened as follows: the main threat from the west and from the north was Kuchluk, the son of Tayan Khan of the Naiman, after the death of his father, he fled to the neighboring tribes. This typical nomadic adventurer gathered around him diverse tribes, the main core of which was the sworn enemies of the Mongols - the Merkits, a harsh and warlike tribe that roamed on a large scale, often coming into conflict with neighboring tribes, into whose lands it invaded, as well as hiring for service to one or another of the nomadic leaders, under whose leadership one could expect to profit from robbery. The old adherents of the Naimans who had gathered near Kuchluk and the bands that had rejoined him could pose a threat to peace in the western regions newly annexed to the Mongol state, which is why Genghis Khan in 1208 sent an army under the command of his best governors Dzhebe and Subutai with the task of destroying Kuchluk.

In this campaign, the Mongols were greatly assisted by the Oirats tribe, through whose lands the path of the Mongol army ran. As early as 1207, the leader of the Oirats, Khotuga-begi, expressed his obedience to Genghis Khan and, as a sign of honor and submission, sent him a white gyrfalcon as a gift. In this campaign, the Oirats served as guides for the troops of Jebe and Subutai, which they led unnoticed by the enemy to his location. In the battle that took place, which ended in a complete victory for the Mongols, the leader of the Merkits, Tokhta-begi, was killed, but the main enemy, Kuchluk, again managed to avoid death in battle or captivity; he found refuge with the elderly Gur-Khan of the Kara-Chinese, who owned the land now called Eastern, or Chinese, Turkestan.

The moral preparation for the campaign against the Golden Kingdom consisted in the fact that Genghis Khan was trying to give it a religious character in the eyes of the Mongols. "Eternally Blue Sky will lead his troops to avenge the previous offenses caused to the Mongols," he said. Before setting out on a campaign, Genghis Khan retired to his wagon, offering prayers for the grant of victory. "Eternal Creator," he prayed, "I armed myself to avenge the blood of my uncles... whom the Jin emperors slew dishonestly. If You approve of my undertaking, send Your help from above, and lead the earth so that people and good and evil spirits unite for overcoming my enemies."

The people and troops surrounding the wagon all this time cried out: "Tengri! Tengri!" (Heaven!) On the fourth day, Genghis Khan came out and announced that Heaven would grant him victory.

The measures taken to secure the northern, western and southern limits of the empire allowed Genghis Khan to concentrate almost all of his available forces for the upcoming campaign. However, for even greater fidelity of success, in order to divert part of the Jin forces in another direction, he enters into an agreement with the recalcitrant vassal of the Golden Kingdom, the Prince of Liaodong, on a simultaneous attack on a common enemy.

In the spring of 1211, the Mongol army sets out on a campaign from its assembly point near the Kerulen River; to the Great Wall of China, she had to go through a path about 750 miles long, for a significant part of its length running through the eastern part of the Gobi Desert, which, however, at this time of the year is not devoid of water and pasture. Numerous herds chased the army for food.

In addition to obsolete war chariots, the Jin army possessed a team of 20 horses, serious, according to the then concepts, military weapons: stone throwers; large crossbows, each of which required a force of 10 people to pull the bowstrings; catapults, which each required the work of 200 people to operate; in addition to all this, the Jin people also used gunpowder for military purposes, for example, for making landmines ignited by means of a drive, for equipping cast-iron grenades, which were thrown at the enemy with catapults for throwing rockets, etc.

Harold Lam sees in the position of Genghis Khan in the Chinese campaign a similarity with the position of Hannibal in Italy. Such an analogy can indeed be seen in the fact that both commanders had to operate far from the sources of their replenishment, in a resource-rich enemy country, against superior forces that could quickly replenish their losses and were led by masters of their craft, since the military art of the Jin people stood, like in Rome during the Punic Wars, at high altitude. Similarly, like Hannibal, who in Italy attracted to his side all the elements that were still weakly soldered to the Romans or dissatisfied with their rule, Genghis Khan could benefit from the national hatred in the enemy’s troops, since the Chinese, who constituted the most numerous, but subordinate contingent in the Jin army, partly with displeasure demolished the supremacy of the Jurchens alien to them by blood, and the Khitans in the army, the descendants of the people who ruled over Northern China before the Jin, i.e., were equally hostile to the latter. the same jurchens.

For all that, the situation obliged Genghis Khan to be cautious: the defeat suffered in China could untie the hands of the western and southern enemies of the Mongol Empire. Even a decisive success had to be achieved with the least possible loss of men and horses. A huge plus of the Mongol army was its excellent knowledge of the enemy army and the country, achieved through preliminary reconnaissance; This reconnaissance was not interrupted during subsequent hostilities, with the immediate goal of finding out the most convenient area for forcing the Great Wall.

This wall in a section about 500 versts long from the intersection with the Yellow River to the area north of Zhongdu (Beijing), i.e. on that section of it, which, covering the capital from the north-west, presents two strong, parallel barriers - the outer and inner walls, spaced one from the other in the place of the greatest distance of two hundred miles. Rightly counting that he can meet the strongest resistance on the shortest path to Chzhund, Chinggis Khan, demonstrating in this direction, with his main forces forces the outer wall on a weakly protected section of 150-200 versts to the west of this shortest direction. The Mongol army meets stronger resistance by passing the outer wall, but the victory won over the Jin commander Yelü Dashi gives into the hands of Genghis Khan the entire territory lying between the outer and inner walls, and allows him to turn its means to his own advantage, of which the most important were the numerous imperial herds of horses grazing here.

After that, the passage through the inner wall on the mountain pass Ju-yun-guan (in Mongolian Khab-chal) was captured by the vanguard of the Mongnai army, which, consisting of three tumens under the command of the best leaders - Mukhali, Jebe and Subutai, preceded the main forces, supporting with them the closest connection and, in turn, had in front of him a veil of reconnaissance detachments of light cavalry. The general command over the troops of the vanguard belonged, apparently, to Jebe-noyon.

Genghis Khan was accompanied on the campaign by his four sons: Jochi, Chagatai, Ogedei and Tului (aka Ike-noyon, i.e. Grand Duke). Three seniors occupied command posts in the army, and the youngest was with his father, who directly commanded the center of the army, which consisted of 100,000 people of the best Mongolian troops.

Having passed the Great Wall, separate groups that made up the main forces dispersed according to the adopted system in different directions for better use of the country's resources. In the very first major battle after crossing the wall, Jebe inflicted a heavy defeat on the Jin people, who had scattered their forces, by going into their rear. It was in this battle that it turned out that the Mongols knew the area much better than their opponent. Meanwhile, the senior princes, who received from their father the task of capturing the districts and cities lying in the north of Shanxi Province in the large bend of the Yellow River, successfully carried out this assignment. After another victory won in the field, the main forces of the Mongol army approached the "Middle capital" of the Jin state, the city of Zhongdu (Beijing), in which the court was located.

Thus, with amazing speed, within a few months, the resistance of the Jin field army was broken and a vast territory with a dozen fortified cities was captured. This success is all the more surprising because the enemy was not at all taken by surprise by the attack of Genghis Khan. Aware of the intentions of the Mongol khan, by the spring of 1211 the Jin managed to prepare for a rebuff. Nevertheless, a few months later, all their hope, until the gathering of new forces in the southern regions of the state, rested only on the impregnability of the walls of Zhongdu.

In fact, Genghis Khan did not expect to overcome this stronghold with his primitive siege weapons and, not yet having data to conclude that its defenders were discouraged in order to risk an assault, in the autumn of 1211 he withdraws his army back behind the Great Wall.

The following year, in 1212, he again approaches the Middle Capital with his main forces, rightly looking at it as a bait to attract the enemy field armies to it in order to rescue them, which he expected to beat in parts. This calculation was justified, and the Jinskis army suffered new defeats from Genghis Khan in the field. A few months later, almost all the lands lying north of the lower reaches of the Yellow River were in his hands. But Zhongdu and a dozen of the strongest cities continued to hold on, since the Mongols were still not prepared for the actions of a siege war. Not so strongly fortified cities were taken by them either by open force or by various tricks, for example, by feigned flight from under the fortress, leaving part of the convoy with property in place, in order to lure the garrison into the field with the prospect of booty and influence the weakening of security measures; if this trick succeeded, the city or the garrison deprived of the protection of the fortress walls were subjected to a surprise attack. In this way, Chebe captured the city of Liaoyang in the rear of the Jin army, which was operating against the Liaodong prince. Other cities were forced to surrender by threats and terror.

In one of the clashes under the walls of Chungdu in the autumn of 1212, Genghis Khan was wounded. The army lifted the blockade of the capital and was again withdrawn behind the Great Wall. Such breaks in the campaign were absolutely inevitable for the possibility of correcting and repairing the exhausted cavalry of the army. Political considerations also played a certain role in this respect, namely the need to keep other neighbors of the state in fear.

The next year, 1213, passed in the same way. The war obviously took on a protracted character. On this occasion, G. Lam expresses the following considerations:

"Genghis Khan could not, like Hannibal, leave garrisons in the cities taken. The Mongols, who were not yet accustomed to defending themselves in fortresses by that time, would be destroyed by the Jin during the winter. to concentrate them for the upcoming battle, took place only as a result of the fact that the surviving field troops were driven into fortified cities.The approach to Zhongdu was aimed at reaching the emperor, but the impregnable walls of the fortress prevented him from taking it.At the same time, the Jin had success over the Liaodong and tanguts, which provided the flanks of the khan... Under these conditions, the ordinary leader of the nomads would be satisfied with the booty of the previous campaigns and the prestige of the winner over the powerful Jin empire and would remain in his nomad camps outside the Great Wall.But Genghis Khan, although wounded, but still adamant, enriched by the experience of the war in the new conditions and tried to use it for subsequent campaigns, while gloomy forebodings were already beginning to sharpen the soul of the ruler of the Golden Kingdom.

In 1206, a new state was formed on the territory of Central Asia from the united Mongol tribes. The assembled leaders of the groups proclaimed their most militant representative, Temujin (Genghis Khan), thanks to whom the Mongol state declared itself to the whole world, as khan. Acting with a relatively small army, it carried out its expansion in several directions at once. The strongest blows of bloody terror fell on the lands of China and Central Asia. The conquests of the Mongols of these territories, according to written sources, had a total character of destruction, although such data were not confirmed by archeology.

Mongol Empire

Six months after his accession to the kurultai (congress of the nobility), the Mongol ruler Genghis Khan began to plan a large-scale military campaign, the ultimate goal of which was to conquer China. Preparing for his first campaigns, he carries out a series of military reforms, strengthening and strengthening the country from the inside. The Mongol Khan understood that in order to wage successful wars, strong rear lines, a solid organization and a protected central government were needed. He establishes a new state structure and proclaims a single code of laws, abolishing the old tribal customs. The entire system of government has become a powerful tool for maintaining the obedience of the exploited masses and helping in the conquest of other peoples.

The young Mongolian state with an effective management hierarchy and a highly organized army was significantly different from the steppe state formations of its time. The Mongols believed in their chosenness, the purpose of which was the unification of the whole world under the rule of their ruler. Therefore, the main feature of the aggressive policy was the extermination of recalcitrant peoples in the occupied territories.

First campaigns: Tangut state

The Mongol conquest of China took place in several stages. The Tangut state of Xi Xia became the first serious target of the Mongol army, since Genghis Khan believed that without his subjugation, further attacks on China would be meaningless. The invasions of the Tangut lands in 1207 and 1209 were elaborate operations where the khan himself was present on the battlefields. They did not bring due success, the confrontations ended with the conclusion of a peace agreement obliging the Tanguts to pay tribute to the Mongols. But in 1227, under the next onslaught of the troops of Genghis Khan, the state of Xi Xia fell.

In 1207, the Mongol troops under the leadership of Jochi were also sent north to conquer the tribes of the Buryats, Tubas, Oirats, Barkhuns, Ursuts and others. In 1208 they were joined by the Uighurs in East Turkestan, and years later the Yenisei Kyrgyz and Karliks submitted.

Conquest of the Jin Empire (Northern China)

In September 1211, the 100,000-strong army of Genghis Khan began the conquest of northern China. The Mongols, using the weaknesses of the enemy, managed to capture several large cities. And after crossing the Great Wall, they inflicted a crushing defeat on the regular troops of the Jin Empire. The path to the capital was open, but the Mongol khan, having sensibly assessed the capabilities of his army, did not immediately storm it. For several years, the nomads beat the enemy in parts, engaging in battle only in open spaces. By 1215, a significant part of the Jin lands was under the rule of the Mongols, and the capital Zhongda was looted and burned. Emperor Jin, trying to save the state from ruin, agreed to a humiliating treaty, which briefly delayed his death. In 1234, the Mongol troops, together with the Song Chinese, finally defeated the empire.

The initial expansion of the Mongols was carried out with particular cruelty and, as a result, Northern China was left practically in ruins.

Conquest of Central Asia

After the first conquests of China, the Mongols, using intelligence, began to carefully prepare their next military campaign. In the autumn of 1219, a 200,000-strong army moved to Central Asia, having successfully captured East Turkestan and Semirechye a year earlier. The pretext for the start of hostilities was a provoked attack on a Mongolian caravan in the border town of Otrar. The invading army acted according to a well-designed plan. One column went to the siege of Otrar, the second - through the desert of Kyzyl-Kum moved to Khorezm, a small detachment of the best soldiers was sent to Khujand, and Genghis Khan himself with the main troops headed for Bukhara.

The state of Khorezm, the largest in Central Asia, possessed military forces in no way inferior to the Mongols, but its ruler was unable to organize a united resistance to the invaders and fled to Iran. As a result, the scattered army became more defensive, and each city was forced to fight for itself. Often there was a betrayal of the feudal elite, colluding with enemies and acting in their own narrow interests. But the common people fought to the last. The selfless battles of some Asian settlements and cities, such as Khujand, Khorezm, Merv, went down in history and became famous for their participating heroes.

The conquest of the Mongols of Central Asia, like China, was swift, and was completed by the spring of 1221. The outcome of the struggle led to dramatic changes in the economic and state-political development of the region.

Consequences of the invasion of Central Asia

The Mongol invasion became a huge disaster for the peoples living in Central Asia. Within three years, the aggressor troops destroyed and razed to the ground a large number of villages and large cities, among which were Samarkand and Urgench. The once rich areas of Semirechye were turned into places of desolation. The entire irrigation system, which had been formed for more than one century, was completely destroyed, oases were trampled and abandoned. The cultural and scientific life of Central Asia suffered irreparable losses.

On the conquered lands, the invaders introduced a strict regime of requisitions. The population of the resisting cities was completely slaughtered or sold into slavery. Only craftsmen who were sent into captivity could escape the inevitable reprisal. The conquest of the Central Asian states became the bloodiest page in the history of the Mongol conquests.

Capture of Iran

Following China and Central Asia, the conquests of the Mongols in Iran and the Caucasus were one of the next steps. In 1221, cavalry detachments under the command of Jebe and Subedei, rounding the Caspian Sea from the south, swept through the northern Iranian regions like a tornado. In pursuit of the fleeing ruler of Khorezm, they subjected the province of Khorasan to severe blows, leaving behind many burnt settlements. The city of Nishapur was taken by storm, and its population, driven into the field, was completely exterminated. The inhabitants of Gilan, Qazvin, Hamadan fought desperately with the Mongols.

In the 30-40s of the 13th century, the Mongols continued to conquer Iranian lands in attacks, only the northwestern regions, where the Ismailis ruled, remained independent. But in 1256 their state fell, in February 1258 Baghdad was taken.

Hike to Dali

By the middle of the XIII century, in parallel with the battles in the Middle East, the conquests of China did not stop. The Mongols planned to make the state of Dali a platform for further attacks on the Song Empire (southern China). They prepared the campaign with particular care, given the difficult mountainous terrain.

The attack on Dali began in the autumn of 1253 under the leadership of Khubilai, the grandson of Genghis Khan. Having sent ambassadors in advance, he offered the ruler of the state to surrender without a fight and submit to him. But by order of the chief minister Gao Taixiang, who actually ran the affairs of the country, the Mongolian ambassadors were executed. The main battle took place on the Jinshajiang River, where Dali's army was defeated and significantly lost in its composition. The nomads entered the capital without much resistance.

Southern China: Song Empire

The wars of conquest of the Mongols in China were stretched out for seven decades. It was the Southern Song that managed to hold out the longest against the Mongol invasion by entering into various agreements with the nomads. Military clashes between the former allies began to intensify in 1235. The Mongolian army, having met with fierce resistance, could not achieve much success. After that, there was a relative calm for a while.

In 1267, numerous Mongol troops again marched to the south of China under the leadership of Khubilai, who made the conquest of the Song a matter of principle. He did not succeed in a lightning capture: for five years the heroic defense of the cities of Sanyang and Fancheng held out. The final battle took place only in 1275 at Dingjiazhou, where the army of the Song Empire lost and was practically defeated. A year later, the capital of Lin'an was captured. The last resistance in the Yaishan area was defeated in 1279, which was the final date for the conquest of China by the Mongols. fell.

Reasons for the success of the Mongol conquests

For a long time, they tried to explain the unbeaten campaigns of the Mongol army by its numerical superiority. However, this statement, due to documentary evidence, is highly controversial. First of all, explaining the success of the Mongols, historians take into account the personality of Genghis Khan, the first ruler of the Mongol Empire. It was the qualities of his character, coupled with talents and abilities, that showed the world an unsurpassed commander.

Another reason for the Mongol victories is the carefully crafted military campaigns. Thorough reconnaissance was carried out, intrigues were woven in the camp of the enemy, weaknesses were sought out. The tactics of capture were honed to perfection. An important role was played by the combat professionalism of the troops themselves, their clear organization and discipline. But the main reason for the success of the Mongols in the conquest of China and Central Asia was an external factor: the fragmentation of states, weakened by internal political turmoil.

- In the XII century, according to the Chinese chronicle tradition, the Mongols were called "Tatars", the concept was identical to the European "barbarians". You should know that modern Tatars are not connected with this people in any way.

- The exact year of birth of the Mongol ruler Genghis Khan is unknown, different dates are mentioned in the annals.

- China and Central Asia did not stop the development of trade relations between the peoples that joined the empire.

- In 1219, the Central Asian city of Otrar (southern Kazakhstan) held back the Mongol siege for six months, after which it was taken as a result of betrayal.

- The Mongol Empire, as a single state, lasted until 1260, then it broke up into independent uluses.

1. The conquest of China by the Mongols

In the XII century. four states coexisted on the territory of modern China, in the north - the Jurchen Empire of Jin, in the northwest - the Tangut state of Western Xia, in the south - the South Sung Empire and the state formation of Nanzhao (Dali) in Yunnan.

This balance of power was the result of foreign invasions of nomadic tribes who settled on Chinese lands. There was no longer a single China. Moreover, when at the beginning of the 13th century. the danger of Mongol conquest loomed over the country, each of the states turned out to be extremely weakened by internal turmoil and was unable to defend its independence

At the northern borders of China, tribes consisting of Tatars, Taichiuts, Kereites, Naimans, Merkits, later known as the Mongols, appeared at the beginning of the 13th century. In the middle of the 12th century, they roamed the territory of the modern Mongolian People's Republic, in the upper reaches of the Heilongjiang river and in the steppes, surrounding Lake Baikal.

The natural conditions of the habitats of the Mongols led to the occupation of nomadic cattle breeding, which emerged from the primitive complex of agricultural-cattle-breeding-hunting. In search of pastures rich in grass and water, suitable for grazing cattle and small cattle, as well as horses, the Mongol Tribes roamed the vast expanses of the Great Steppe. Domestic animals supplied the nomads with food. Felt was made from wool - a building material for yurts, shoes and household items were made from leather. Handicraft products were used for domestic consumption, while livestock was exchanged for agricultural products and urban crafts of settled neighbors necessary for nomads. The significance of this trade was all the more significant, the more diversified the nomadic pastoralism became. The development of Mongolian society was largely stimulated by ties with China. So, it was from there that iron products penetrated into the Mongolian steppes. The experience of blacksmithing of Chinese masters, used by the Mongols to make weapons, was used by them in the struggle for pastures and slaves

The personally free arats were the central figure of Mongolian society. Under the conditions of extensive nomadic pastoralism, these ordinary nomads grazed cattle, sheared sheep, and made traditional carpets, which are necessary in every yurt. In their economy, the labor of prisoners of war converted into slavery was sometimes used.

In the nomadic society of the Mongols, a significant transformation took place over time. Initially, the traditions of the tribal community were sacredly observed. So, for example, during the constant nomadic life, the entire population of the clan in the camps was located in a circle around the yurt of the tribal elder, thereby constituting a kind of camp-kuren. It was this tradition of the spatial organization of society that helped to survive in difficult, sometimes life-threatening steppe conditions, when the nomad community was still underdeveloped and needed the constant cooperation of all its members. Starting from the end of the XII century. with the growth of property inequality, the Mongols began to roam the villages, i.e. small family groups connected by ties of consanguinity. With the decomposition of the clan in the course of a long struggle for power, the first tribal unions were formed, headed by hereditary rulers who expressed the will of the tribal nobility - noyons, people of the “white bone”.

Among the heads of clans, Yesugei-Batur (from the Borjigin clan), who wandered in the steppe expanses to the east and north of Ulaanbaatar, and became the leader-kagan of a powerful clan - a tribal association, especially exalted. Yesugei-batur was succeeded by his son Temujin. Having inherited the warlike character of his father, he gradually subjugated the lands in the West - to the Altai Range and in the East - to the upper Heilongjiang, uniting almost the entire territory of modern Mongolia. In 1203, he managed to defeat his political rivals - Khan Jamuhu, and then over Wang Khan.

In 1206, at the congress of noyons - kurultai - Temuchin was proclaimed the all-Mongolian ruler under the name of Genghis Khan (c. 1155-1227). He called his state Mongolian and immediately began aggressive campaigns. The so-called Yasa of Genghis Khan was adopted, which legitimized aggressive wars as a way of life for the Mongols. In this occupation, which became everyday for them, the central role was assigned to the cavalry, hardened by constant nomadic life.

The pronounced military way of life of the Mongols gave rise to a peculiar institution of nukerism - armed warriors in the service of the noyons, recruited mainly from tribal nobility. From these ancestral squads, the armed forces of the Mongols were created, sealed by blood ancestral ties and headed by leaders tested in long exhausting campaigns. In addition, the conquered peoples often joined the troops, strengthening the power of the Mongol army.

Wars of conquest began with the invasion of the Mongols in 1209 on the state of Western Xia. The Tanguts were forced not only to recognize themselves as vassals of Genghis Khan, but also to take the side of the Mongols in the struggle against the Jurchen Jin Empire. Under these conditions, the South Sung government also went over to the side of Genghis Khan: trying to take advantage of the situation, it stopped paying tribute to the Jurchens and concluded an agreement with Genghis Khan. Meanwhile, the Mongols began to actively establish their power over Northern China. In 1210 they invaded the state of Jin (in the Shanxi province).

At the end of the XII - beginning of the XIII century. The Jin Empire underwent great changes. Part of the Jurchens began to lead a settled way of life and engage in agriculture. The process of disengagement in the Jurchen ethnos sharply aggravated the contradictions within it. The loss of monolithic unity and former combat capability became one of the reasons for the defeat of the Jurchens in the war with the Mongols. In 1215, Genghis Khan captured Beijing after a long siege. His commanders led their troops to Shandong. Then part of the troops moved to the northeast in the direction of Korea. But the main forces of the Mongol army returned to their homeland, from where in 1218 they began a campaign to the West. In 1218, having captured the former lands of the Western Liao, the Mongols reached the borders of the Khorezm state in Central Asia.

In 1217, Genghis Khan again attacked the Western Xia, and then eight years later launched a decisive offensive against the Tanguts, inflicting a bloody pogrom on them. The conquest of the Western Xia by the Mongols ended in 1227. The Tanguts were slaughtered almost without exception. Genghis Khan himself participated in their destruction. Returning home from this campaign, Genghis Khan died. The Mongolian state was temporarily headed by his youngest son Tului.

In 1229, the third son of Genghis Khan, Ogedei, was proclaimed the great khan. The capital of the empire was Karakorum (southwest of present-day Ulaanbaatar).

Then the Mongol cavalry headed south of the Great Wall of China, seizing the lands that remained under the rule of the Jurchens. It was at this difficult time for the state that Ogedei concluded an anti-Jurchen military alliance with the South Sung emperor, promising him the lands of Henan. Going to this alliance, the Chinese government hoped with the help of the Mongols to defeat the old enemies - the Jurchens and return the lands they had seized. However, these hopes were not destined to come true.

The war in Northern China continued until 1234 and ended with the complete defeat of the Jurchen kingdom. The country was terribly devastated. Having barely ended the war with the Jurchens, the Mongol khans unleashed hostilities against the southern Sungs, terminating the treaty with them. A fierce war began, which lasted for about a century. When the Mongol troops invaded the Sung Empire in 1235, they met with a fierce rebuff from the population. The besieged cities stubbornly defended themselves. In 1251, it was decided to send a large army to China, led by Khubilai. The great Khan Mongke, who died in Sichuan, took part in one of the campaigns.

Beginning in 1257, the Mongols attacked the South Sung Empire from different sides, especially after their troops marched to the Dai Viet borders and subjugated Tibet and the state of Nanzhao. However, the Mongols managed to occupy the southern Chinese capital of Hangzhou only in 1276. But even after that, detachments of Chinese volunteers continued to fight. Fierce resistance to the invaders was provided, in particular, by the army led by a major dignitary Wen Tianxiang (1236-1282).

After a long defense in Jiangxi in 1276, Wen Tianxiang was defeated and taken prisoner. He preferred the death penalty to serving Khubilai. Patriotic poems and songs, created by him in prison, were widely known. In 1280, in battles at sea, the Mongols defeated the remnants of the Chinese troops.

From the book Reconstruction of World History [text only] author6. BIBLICAL CONQUERATION OF THE PROMISED LAND IS THE HORDEAN-ATAMAN = TURKISH CONQUEST OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY 6.1. A GENERAL VIEW ON THE HISTORY OF THE BIBLICAL EXODUS Everyone is well aware of the biblical story of the exodus of 12 tribes of Israel from Egypt under the leadership of a prophet

From the book Piebald Horde. History of "ancient" China. author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich11.1. The Manchurian conquest of the 17th century is the beginning of a reliable history of China So, we have come to the following, at first glance, completely impossible, but apparently CORRECT thought: THE BEGINNING OF A RELIABLE WRITTEN HISTORY OF CHINA IS THE AGE OF THE COMING TO POWER IN CHINA

From the book of Rurik. Collectors of the Russian Land author Burovsky Andrey MikhailovichChapter 18 The Rurikovichs who lived under the Mongols and together with the Mongols Politics of the Mongols The Mongols willingly accepted the defeated into their army. The number of those who came from the steppes decreased, new warriors from the conquered peoples came in their place. The first of the princes who began to serve

author Grousset ReneThe conquest of northern China by Genghis Khan After Mongolia was united, Genghis Khan set about conquering northern China. First, he attacked the kingdom of Xi-xia, founded in Kan-su, in Alashan and Ordos by the Tangut horde, the Tibetan race and the Buddhist religion. Like us

From the book Empire of the Steppes. Attila, Genghis Khan, Tamerlane author Grousset ReneThe Mongol conquest of the ancient empire of the Karakitays While Genghis Khan began to conquer northern China, one of his personal enemies, Kuchlug, the son of the last leader of the Naiman, became the master of the empire of Central Asia, the empire of the Karakit Gur Khans. We know

From the book Empire of the Steppes. Attila, Genghis Khan, Tamerlane author Grousset ReneThe Mongol conquest of Western Persia When Ogedei took the throne, the task was to recapture Iran. We know that in November 1221, Genghis Khan forced Jalal ad-Din Manguberdi, heir to the Khorezm Empire, to hide in India. Sultan of Delhi - Turk Iltutmish accepted

From the book Empire of the Steppes. Attila, Genghis Khan, Tamerlane author Grousset ReneConquest of China by the Manzhurs The Tungus peoples, as we have already seen, occupied exclusively vast expanses of northeast Asia: Manchuria (Manchuria, Dakhurs, Solons, Manegirs, Birars and Golds), coastal Russian provinces (Orochens), the eastern coast of the middle

From the book Russian army 1250-1500. author Shpakovsky Vyacheslav OlegovichTHE CONQUEST OF RUSSIA BY THE MONGOLS In 1237 the Mongols invaded the Ryazan principality. Three years later, the northeastern and southern regions of the country lay in ruins. Moving deep into the rich Russian principalities, the invaders destroyed fortified cities and strong armies. On the battlefields

From the book History of China author Meliksetov A.V.1. The fall of the Ming dynasty and the conquest of China by the Manchus In the 30-40s. 17th century the Chinese state was at the final stage of the next dynastic cycle. As in previous eras, this process was accompanied by an increase in the tax burden, the concentration of land in

From the book Japan in the war 1941-1945. [with illustrations] author Hattori Takushiro From the book Rus and Rome. Russian-Horde Empire on the pages of the Bible. author Nosovsky Gleb VladimirovichChapter 3 The conquest of the Promised Land is the Ottoman = Ataman conquest of the 15th century 1. General view of the history of the biblical Exodus Everyone knows the biblical story of the Exodus of the twelve Israelite tribes from Egypt under the leadership of the prophet Moses. She is described in

From the book History of Korea: from antiquity to the beginning of the XXI century. author Kurbanov Sergey Olegovich§ 2. Diplomatic relations between Goryeo and the Mongols. Subjugation of Koryo to the Mongol Yuan Dynasty of China

From the book Zoroastrians. Beliefs and customs by Mary BoyceThe conquest of Iran by the Turks and Mongols The Book of Muslim Scholars was composed on the eve of a new terrible disaster, before an even more terrible storm broke out over Iran. The 9th and 10th centuries are called the Persian interlude, the period "between the Arabs and the Turks." At the beginning of the XI century.

From the book Empire of the Turks. great civilization author Rakhmanaliev RustanExternal expansion. Genghis Khan's Conquest of Northern China After Genghis Khan established power in the steppe under his command, his policy gradually switched to organizing and conducting military campaigns. Joining interests to expand nomadic

From the book Japan in the war 1941-1945. author Hattori Takushiro2. Turn in policy towards the new government of China. Determining the main course to seize China During the war, Japan became more and more eager to solve the Chinese problem as soon as possible and direct all attention to the war with America

From the book Bysttvor: the existence and creation of the Rus and Aryans. Book 1 author SvetozarThe Conquest of China by the Rus and the Aryans of the Shang Dynasty The opposition of the Chinese to the Rus and the Aryans caused rejection of many of the rules established by them. The first step in this direction was the violation of the rules for organizing the life of communities. Russ and Aryans strictly observed the Ancestral Foundations, therefore their

The history of the Mongolian peoples has been closely connected with the history of China for many centuries. It was to protect against them and their nomadic neighbors that the Great was built. Mongol cavalry razed Chinese cities to the ground during the time of Genghis. A little later, almost a hundred years later, it fell under the control of the Mongol Yuan dynasty, and in the 17th-18th centuries, the Manchus included Inner and Outer Mongolia, Oirat-Mongolia (the Dzungar Khanate) and Tannu-Uriankhai into the Qing Empire. Only after the Xinhai revolution in China and the national revolution in Mongolia itself, the Mongols began to gradually get out of China's control. This process ended with the creation of the MPR in 1924.

Huns

Perhaps the contacts of the Chinese with the Mongols took place long before Genghis, back in the time of the Huns, the first information about which dates back to the 4th century BC. Already a few decades after their appearance on the historical horizon, the Huns, who lived on the territory of modern Mongolia, begin to actively fight with the Chinese states. By the end of the 3rd century, they create the first empire of nomadic tribes, which lasted about three centuries. Information about this empire is fragmentary and obtained mainly from Chinese sources.

There is only one problem - it is impossible to prove the relationship of the Huns with the Mongols. The version about the Mongol-speaking nomads has been supported by many historians since the 18th century. According to this theory, the name "Xiongnu" comes from the Mongolian "hun", which means "man". But there are other versions that record the Turkic peoples, the Yenisei peoples and the Persians as descendants of the Xiongnu. Nevertheless, in 2011 Mongolia officially celebrated the 2220th anniversary of its own statehood. For the Mongols, kinship with the Xiongnu is a fact that does not need additional evidence.

Conquest of China by Genghis Khan and his successors

By 1215, Genghis Khan almost completely captured the territory of the Jurchen state of Jin (Manchuria). A dozen years later (1226-27), the Mongols conquer the Tangut kingdom, located on the territory of the modern provinces of Gansu and Shaanxi. In 1231-1234, Ogedei and Tolui smashed the Jin state. In 1235, the Mongols began a war with the Song Empire. Khan Kubilai completed the conquest of China, besieging the cities of Fancheng and Xiangyang in 1267, and by 1279 he finally defeated the Chinese resistance forces in the battle of Yashan.

At the initial stage of the conquests, the nomads often did not hold the occupied territories. Making their raids, the maneuverable cavalry of the steppes destroyed the Chinese troops and fortifications, and after the departure of the Mongols, the Chinese again erected fortifications and filled them with garrisons. Later, the tactics changed, and the successors of the cause of Genghis Khan included Chinese lands in the Mongol Yuan Empire, which subsequently lost contact with other Mongol states.

Mongol Yuan Empire

The Mongolian state of Yuan, whose main constituent territory was China, existed from 1271 to 1368. It was founded by the grandson of Genghis Khan Khubilai. Back in 1215, the Mongols burned to the ground the city of Zhongdu, located just southwest of the modern center. In 1267, a little to the north, Khubilai built a new city - Khanbalik. Later, when the Ming dynasty came to power, one of the most important was erected on the foundations of the destroyed palaces of Khanbalik -.

The Mongol rulers adopted a lot from the imperial dynasties of the Celestial Empire that preceded them. They carried out reforms to strengthen central government and reform economic institutions, and the Yuan provincial government structure was adopted with minimal changes by the subsequent Ming and Qing dynasties. The fall of the Yuan state was caused by many reasons, one of them was the fact that the representatives of the Mongolian elite ceased to be their own in other parts of the "Mongolian world", but did not become their own for the Chinese. In 1351, the Red Turban Rebellion broke out, which had a pronounced anti-Mongolian character. Beijing fell in 1368 and the Ming Dynasty took over. For several more years, the supporters of the Yuan dynasty held their positions in Guizhou and Yunnan, but by 1381 they were finally defeated.

Mongolian states in the Qing Empire and after the Xinhai Revolution