The southern neighbors of Kievan Rus are the Polovtsians. The value of the struggle of Russia with the Polovtsy

Raids on Russia Polovtsy

Prepared by the teacher

primary school MBOU "Secondary school No. 2 named after. E. V. Kamysheva

Yurieva Elena Gennadievna

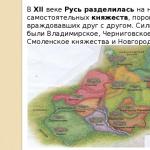

AT XII century Russia divided for several independent principalities sometimes at odds with each other. The strongest were Vladimir, Chernigov, Galicia, Smolensk principalities and Novgorod land.

A special place at this time is occupied by the struggle of Russia with the Polovtsians. Polovtsy - steppe nomadic people, neighbors of Russia. Back in the 11th century, Russian-Polovtsian clashes began. In memory of the Polovtsians in the south of Russia, stone statues remained on ancient burial mounds, where warriors were buried. The sculptures depict warriors or women and are called "stone women"

Russian princes tried to repel the attacks of the Polovtsy near the walls of their fortresses. But this was of little use.

First of all, the Polovtsians could attack in a huge horde, and the forces of the city and the local prince were often not enough for defense.

Secondly sadly, the Polovtsians were often brought to Russia by the Russian princes themselves. They were at enmity with each other and used warlike nomads to attack an objectionable neighbor.

Prince Vladimir Monomakh proposed his own way of fighting the Polovtsy.

Grand Duke Vladimir Monomakh

In the 12th century Cumans lived north of the Black and Azov Seas, from the Volga and Danube. Nomads served the Grand Duke for money, were his mercenaries and at the same time plundered the southern lands.

From 1169, the heyday of Vladimir Russia begins

Immediately after the death of Andrei Bogolyubsky (son of Yuri Dolgoruky), strife began between his brothers and nephews.

It ended with the victory of Vsevolod Yurievich, who took the throne of Vladimir for 32 years. Since the Grand Duke had a large family, the people called him Vsevolod the Big Nest. Although the Grand Duke and his sons spent their whole lives in military campaigns, under Vsevolod, Vladimir Rus reached its highest peak.

Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky

Prince Vsevolod Big Nest

In 1185, Igor, Prince of Novgorod, the Seversk land, conceived a military campaign against the Polovtsy, who lived in the steppes south of Russia. For many years, the Russians and the Polovtsy were at enmity with each other, and it seemed that this enmity had no end and edge, because each prince dreamed only of personal glory and each principality fought the Polovtsy alone.

Prince Igor wanted to go through the entire Polovtsian steppe and reach the city of Tmutarakini, built by the Russians in the 10th century on the Taman Peninsula, between the Black and Azov Seas.

But Igor and Vsevolod were able to restore stamina and courage to their warriors. The army went on a campaign. However, the Polovtsians lured the Russians deep into the steppe and surrounded them. By the banks of the river Kayali the battle began. The warriors fought gloriously for two days. And on the third, when the sun was at its zenith, Igor's banners fell.

V. Vasnetsov. After the battle of Igor Svyatoslavovich with the Polovtsy

In an unequal battle, Igor himself was wounded and taken prisoner.

“The grass will droop with pity in the field, and with anguish they bowed to the ground of the tree ... Our Russian land has weakened, a groan has risen on it”

"The Tale of Igor's Campaign"

Meanwhile, the news of Igor's defeat reached the city. Putivl, where Princess Yaroslavna was waiting for the return of her husband. Hearing the evil news, she climbed the city wall and began to mourn the dead Russian soldiers.

"The Tale of Igor's Campaign"

The Polovtsy could not take advantage of the victory over Igor's squad. Svyatoslav of Kyiv with difficulty, but managed to beat off their raid.

Kyiv Prince Svyatoslav saw a terrible dream. He dreamed of the banks of the Kayala, strewn with the bodies of dead soldiers. And he realized that trouble had happened to Igor. And he turned to all the Russian princes with a proposal to end quarrels and hostility, to unite as in the good old days against a common enemy.

Meanwhile, Igor was able to persuade the Polovtsy Ovlur to help him escape from captivity. When the Polovtsian camp was sound asleep, Ovlur whistled for Igor to mount his horse. Despite the chase, the prince's escape was a success.

The return of Igor to Russia caused general joy. The Tale of Igor's Campaign is written about his campaign. In this poem, Igor is glorified as a commander who called on the Russian princes to unite against the enemy. But the princes did not unite, and the Polovtsy continued to attack Russian lands.

The last raid of the Polovtsy took place in 1234 year.

Sources:

1) “Illustrated history of Russia. VIII- Beginning of the XX century» Borzova L.P.

2) "Victory of the Russian army and navy" Filyushkin A.I.

3) "Ancient Russia" Aleshkov V.I.

4) "History of Russia" Golubev A.V., Telitsin V.L., Chernikova T.V.

The struggle of Russia with the Polovtsy. Civil strife.

By the middle of the XI century. the Kipchak tribes, coming from Central Asia, conquered all the steppe spaces from the Yaik (Ural River) to the Danube, including the north of Crimea and the North Caucasus.

Separate clans, or “tribes”, of the Kipchaks united into powerful tribal unions, the centers of which were primitive winter quarters. The khans who led such associations could raise tens of thousands of warriors, soldered by tribal discipline and posing a terrible threat to neighboring agricultural peoples, on a campaign. The Russian name of the Kipchaks - "Polovtsy" - came, as they say, from the Old Russian word "polova" - straw, because the hair of these nomads was light, straw-colored.

The first appearance of the Polovtsy in Russia

In 1061, the Polovtsy first attacked Russian lands and defeated the army of the Pereyaslav prince Vsevolod Yaroslavich. Since that time, for more than a century and a half, they have continuously threatened the borders of Russia. This struggle, unprecedented in its scale, duration and bitterness, occupied a whole period of Russian history. It unfolded along the entire border of the forest and the steppe - from Ryazan to the foothills of the Carpathians. After spending the winter near the sea coasts (in the Sea of \u200b\u200bAzov), the Polovtsians in the spring began to roam to the north and appeared in the forest-steppe regions in May. They attacked more often in the fall to profit from the fruits of the harvest, but the leaders of the Polovtsy, trying to take the farmers by surprise, constantly changed tactics, and an attack could be expected at any time of the year, in any principality of the steppe borderlands. It was very difficult to repel the attacks of their flying detachments: they appeared and disappeared suddenly, before the princely squads or militias of the nearest cities were in place. Usually the Polovtsians did not besiege fortresses and preferred to ravage villages, but even the troops of an entire principality often turned out to be powerless before the large hordes of these nomads.

Until the 90s. 11th century the annals report almost nothing about the Polovtsians. However, judging by the memoirs of Vladimir Monomakh about his youth, given in his Teaching, then during all the 70s and 80s. 11th century on the border, the “small war” continued: endless raids, chases and skirmishes, sometimes with very large forces of nomads.

Cuman offensive

In the early 90s. 11th century Polovtsy, who roamed along both banks of the Dnieper, united for a new onslaught on Russia. In 1092, "the army was great from the Polovtsians and from everywhere." The nomads captured three cities - Pesochen, Perevoloka and Priluk, destroyed many villages on both banks of the Dnieper. The chronicler is eloquently silent about whether any rebuff was given to the steppe dwellers.

The following year, the new Kyiv prince Svyatopolk Izyaslavich recklessly ordered the arrest of the Polovtsian ambassadors, which gave rise to a new invasion. The Russian army, which came out to meet the Polovtsy, was defeated at Trepol. During the retreat, crossing in a hurry across the river Stugna flooded with rain, many Russian soldiers drowned, including the Pereyaslav prince Rostislav Vsevolodovich. Svyatopolk fled to Kyiv, and the huge forces of the Polovtsy besieged the city of Torks, who had settled since the 50s. 11th century along the river Ros, - Torchesk. The Kyiv prince, having gathered a new army, tried to help the Torques, but was again defeated, having suffered even greater losses. Torchesk defended heroically, but in the end the water supply ran out in the city, it was taken by the steppes and burned. Its entire population was driven into slavery. The Polovtsy again ravaged the outskirts of Kyiv, capturing thousands of prisoners, but they, apparently, failed to rob the left bank of the Dnieper; he was defended by Vladimir Monomakh, who reigned in Chernigov.

In 1094, Svyatopolk, not having the strength to fight the enemy and hoping to get at least a temporary respite, tried to make peace with the Polovtsy by marrying the daughter of Khan Tugorkan - the one whose name the creators of epics over the centuries have changed into "Tugarin's Snake" or "Tugarin Zmeevich" . In the same year, Oleg Svyatoslavich from the family of Chernigov princes, with the help of the Polovtsy, drove Monomakh from Chernigov to Pereyaslavl, giving the surroundings of his native city to the allies for plunder.

In the winter of 1095, near Pereyaslavl, Vladimir Monomakh's combatants destroyed the detachments of two Polovtsian khans, and in February the troops of the Pereyaslav and Kyiv princes, who have since become permanent allies, made their first campaign in the steppe. Prince Oleg of Chernigov evaded joint actions and preferred to make peace with the enemies of Russia.

In the summer the war resumed. The Polovtsy besieged the town of Yuryev for a long time on the Ros River and forced the inhabitants to flee from it. The city was burned down. Monomakh on the east coast successfully defended himself, having won several victories, but he clearly lacked strength. The Polovtsians struck in the most unexpected places, and the Chernigov prince established very special relations with them, hoping to strengthen his own independence and protect his subjects by ruining his neighbors.

In 1096, Svyatopolk and Vladimir, completely enraged by Oleg’s treacherous behavior and his “stately” (i.e., proud) answers, drove him out of Chernigov and besieged him in Starodub, but at that time large forces of the steppe people launched an offensive along both banks of the Dnieper and immediately broke through to the capitals of the principalities. Khan Bonyak, who led the Azov Polovtsy, flew into Kyiv, and Kurya and Tugorkan laid siege to Pereyaslavl. The troops of the allied princes, having nevertheless forced Oleg to ask for mercy, set off on an accelerated march towards Kyiv, but, not finding Bonyak there, who left, avoiding a collision, crossed the Dnieper at Zarub and on July 19, unexpectedly for the Polovtsy, appeared near Pereyaslavl. Not giving the enemy the opportunity to line up for battle, the Russian soldiers, having forded the Trubezh River, hit the Polovtsians. Those, without waiting for the fight, ran, dying under the swords of their pursuers. The destruction was complete. Among those killed was Svyatopolk's father-in-law, Tugorkan.

But on the same days, the Polovtsians almost captured Kyiv: Bonyak, making sure that the troops of the Russian princes had gone to the left bank of the Dnieper, approached Kyiv a second time and at dawn tried to suddenly break into the city. For a long time afterwards, the Polovtsy recalled how an annoyed khan with a saber cut the gate leaves that slammed shut in front of his very nose. This time, the Polovtsy burned the princely country residence and ruined the Caves Monastery, the most important cultural center of the country. Urgently returning to the right bank, Svyatopolk and Vladimir pursued Bonyak beyond the Ros, to the very Southern Bug.

The nomads felt the strength of the Russians. Since that time, Torks and other tribes, as well as individual Polovtsian clans, began to come to Monomakh from the steppe to serve. In such a situation, it was necessary to quickly unite the efforts of all Russian lands in the fight against the steppe nomads, as was the case under Vladimir Svyatoslavich and Yaroslav the Wise, but other times came - the era of inter-princely wars and political fragmentation. The Lyubech congress of princes in 1097 did not lead to an agreement; the Polovtsy also took part in the strife that began after him.

Unification of Russian princes to repulse the Polovtsy

Only in 1101 did the princes of the southern Russian lands reconcile with each other, and the very next year, “intentioning to dare on the Polovtsy and go to their lands.” In the spring of 1103, Vladimir Monomakh came to Svyatopolk in Dolobsk and convinced him to set out on a campaign before the start of field work, when the Polovtsian horses after wintering had not yet had time to gain strength and were not able to escape from the chase.

The united army of seven Russian princes in boats and horses along the banks of the Dnieper moved to the rapids, from where it turned deep into the steppe. Having learned about the movement of the enemy, the Polovtsy sent a patrol - “watchman”, but Russian intelligence “guarded” and destroyed it, which allowed the Russian commanders to take full advantage of surprise. Not ready for battle, the Polovtsy, at the sight of the Russians, fled, despite their huge numerical superiority. Twenty khans died during the pursuit under Russian swords. Huge booty fell into the hands of the winners: captives, herds, wagons, weapons. Many Russian prisoners were released. One of the two main Polovtsian groups was dealt a heavy blow.

But in 1107, Bonyak, who retained his strength, laid siege to Luben. The troops of other khans also came here. The Russian army, which this time included the Chernigovites, again managed to catch the enemy by surprise. On August 12, suddenly appearing in front of the Polovtsian camp, the Russians rushed to the attack with a battle cry. Not trying to resist, the Polovtsy fled.

After such a defeat, the war moved to the territory of the enemy - to the steppe, but first a split was introduced into its ranks. In winter, Vladimir Monomakh and Oleg Svyatoslavich went to Khan Aepa and, having made peace with him, became related, marrying their sons Yuri and Svyatoslav to his daughters. At the beginning of the winter of 1109, the governor of Monomakh, Dmitry Ivorovich, reached the Don and there he captured "a thousand vezh" - Polovtsian wagons, which upset the military plans of the Polovtsians for the summer.

The second big campaign against the Polovtsians, the soul and organizer of which again became Vladimir Monomakh, was undertaken in the spring of 1111. The warriors set out even in the snow. The infantry rode in sledges to the Khorol River. Then they went to the southeast, "bypassing many rivers." Four weeks later, the Russian army went to the Donets, dressed in armor and served a prayer service, after which they headed for the capital of the Polovtsians - Sharukan. The inhabitants of the city did not dare to resist and came out with gifts. The Russian captives who were here were released. A day later, the Polovtsian city of Sugrov was burned, after which the Russian army moved back, surrounded on all sides by the growing Polovtsian detachments. On March 24, the Polovtsy blocked the path of the Russians, but were driven back. The decisive battle took place in March on the banks of the small river Salnitsa. In a difficult battle, Monomakh's regiments broke through the Polovtsian encirclement, enabling the Russian army to leave safely. The prisoners were taken. The Cumans did not pursue the Russians, admitting their failure. To participate in this campaign, the most significant of all committed by him, Vladimir Vsevolodovich attracted many clergy, giving it the character of a cross, and achieved his goal. The fame of Monomakh's victory reached "even as far as Rome."

However, the forces of the Polovtsy were still far from being broken. In 1113, having learned about the death of Svyatopolk, Ayepa and Bonyak immediately tried to test the strength of the Russian border by besieging the fortress of Vyr, but, having received information about the approach of the Pereyaslav army, they immediately fled - the psychological turning point in the war, achieved during the campaign of 1111, had an effect.

In 1113-1125, when Vladimir Monomakh reigned in Kyiv, the fight against the Polovtsy took place exclusively on their territory. The victorious campaigns that followed one after another finally broke the resistance of the nomads. In 1116, the army under the command of Yaropolk Vladimirovich - a permanent participant in his father's campaigns and a recognized military leader - defeated the nomad camps of the Don Polovtsy, taking three of their cities and bringing many captives.

The Polovtsian rule in the steppes collapsed. The uprising of the tribes subject to the Kipchaks began. For two days and two nights, Torks and Pechenegs brutally fought with them at the Don, after which, having fought back, they retreated. In 1120, Yaropolk went with his army far beyond the Don, but did not meet anyone. The steppes were empty. The Polovtsy migrated to the North Caucasus, to Abkhazia, to the Caspian Sea.

The Russian plowman lived quietly in those years. The Russian border moved south. Therefore, the chronicler of one of the main merits of Vladimir Monomakh considered that he was "most fearless of the filthy" - he was more than any of the Russian princes afraid of the pagan Polovtsy.

Resumption of Polovtsian raids

With the death of Monomakh, the Polovtsy perked up and immediately tried to capture the Torks and rob the Russian border lands, but were defeated by Yaropolk. However, after the death of Yaropolk, the Monomashichs (descendants of Vladimir Monomakh) were removed from power by Vsevolod Olgovich, a friend of the Polovtsy who knew how to hold them in his hands. Peace was concluded, and news of the Polovtsian raids disappeared from the pages of chronicles for some time. Now the Polovtsy appeared as allies of Vsevolod. Ruining everything in their path, they went with him on campaigns against the Galician prince and even against the Poles.

After Vsevolod, the Kyiv table (reigning) went to Izyaslav Mstislavich, the grandson of Monomakh, but now his uncle, Yuri Dolgoruky, began to actively play the "Polovtsian card". Deciding to get Kyiv at any cost, this prince, son-in-law of Khan Aepa, five times led the Polovtsy to Kyiv, plundering even the surroundings of his native Pereyaslavl. In this he was actively helped by his son Gleb and brother-in-law Svyatoslav Olgovich, the second son-in-law of Aepa. In the end, Yuri Vladimirovich established himself in Kyiv, but he did not have to reign for a long time. Less than three years later, the people of Kiev poisoned him.

The conclusion of an alliance with some tribes of the Polovtsy did not at all mean an end to the raids of their brethren. Of course, the scale of these raids could not be compared with the attacks of the second half of the 11th century, but the Russian princes, more and more occupied with strife, could not organize a reliable unified defense of their steppe borders. In such a situation, the Torks and other small nomadic tribes settled along the Ros River, who were dependent on Kyiv and bore the common name “black hoods” (that is, hats), turned out to be indispensable. With their help, the militant Polovtsy were defeated in 1159 and 1160, and in 1162, when the “Polovtsy many”, having swooped down on Yuryev, captured many Tork wagons there, the Torks themselves, without waiting for the Russian squads, began to pursue the raiders and, having caught up, recaptured the prisoners and even captured more than 500 Polovtsy.

Constant strife practically nullified the results of the victorious campaigns of Vladimir Monomakh. The power of the nomadic hordes weakened, but the Russian military force was also split up - this equalized both sides. However, the cessation of offensive operations against the Kipchaks allowed them to again accumulate forces for an onslaught on Russia. By the 70s. 12th century in the Don steppe, a large state formation was again formed, headed by Khan Konchak. Emboldened, the Polovtsy began to rob merchants on the steppe paths (paths) and along the Dnieper. The activity of the Polovtsians also increased at the borders. One of their troops was defeated by the Novgorod-Seversky prince Oleg Svyatoslavich, but near Pereyaslavl they defeated the detachment of the governor Shvarn.

In 1166, the Kyiv prince Rostislav sent a detachment of the governor Volodyslav Lyakh to escort merchant caravans. Soon Rostislav mobilized the forces of ten princes to protect the trade routes.

After the death of Rostislav, Mstislav Izyaslavich became the prince of Kyiv, and already under his leadership in 1168 a new large campaign to the steppe was organized. In early spring, 12 influential princes, including the Olgovichi (descendants of Prince Oleg Svyatoslavich), who temporarily quarreled with their steppe relatives, responded to Mstislav’s call to “search for their fathers and grandfathers for their ways and their honor.” The Polovtsy were warned by a defector slave, nicknamed Koschey, and they fled, leaving their “veshes” with their families. Upon learning of this, the Russian princes rushed in pursuit and seized the camps at the mouth of the Orel River and along the Samara River, and the Polovtsy themselves, having caught up with the Black Forest, pressed against it and killed, almost without suffering losses.

In 1169, two hordes of Polovtsians simultaneously approached Korsun on the Ros River and Pesochen near Pereyaslavl on both banks of the Dnieper, and each demanded a Kyiv prince to conclude a peace treaty. Without thinking twice, Prince Gleb Yurievich rushed to Pereyaslavl, where his 12-year-old son then ruled. The Azov Polovtsians of Khan Togly, who were standing near Korsun, barely learned that Gleb had crossed to the left bank of the Dnieper, immediately rushed into the raid. Bypassing the fortified line on the Ros rivers, they devastated the surroundings of the towns of Polonny, Semych and Tithe in the upper reaches of the Sluch, where the population felt safe. The steppe dwellers, who fell like snow on their heads, plundered the villages and drove the captives into the steppe.

Having made peace at Pesochen, Gleb learned on the way to Korsun that no one was there. There were few troops with him, and even part of the soldiers had to be sent to intercept the treacherous nomads. Gleb sent his younger brother Mikhalko and the governor Volodislav to beat off the captives with one and a half thousand Berendey nomads and a hundred Pereyaslavtsy.

Having found a trace of the Polovtsian raid, Mikhalko and Volodyslav, having shown amazing military skills, in three consecutive battles not only recaptured the captives, but also defeated the enemy, who outnumbered them at least ten times. Success was also ensured by the skillful actions of the intelligence of the Berendeys, who famously destroyed the Polovtsian patrol. As a result, a horde of more than 15 thousand horsemen was defeated. One and a half thousand Polovtsians were taken prisoner.

Two years later, Mikhalko and Volodyslav, acting in similar conditions according to the same scheme, again defeated the Polovtsy and saved 400 captives from captivity, but these lessons did not go to the Polovtsy for the future: new ones appeared to replace the dead seekers of easy prey from the steppe. A rare year passed without a major raid, noted by the annals.

In 1174, the young Novgorod-Seversky prince Igor Svyatoslavich distinguished himself for the first time. He managed to intercept the khans Konchak and Kobyak returning from the raid at the crossing over the Vorskla. Attacking from an ambush, he defeated their horde, repelling the captives.

In 1179, the Polovtsians, who were brought by Konchak - the "evil boss" - ravaged the environs of Pereyaslavl. The chronicle noted that especially many children died during this raid. However, the enemy was able to escape with impunity. And the next year, on the orders of his relative, the new Kyiv prince Svyatoslav Vsevolodovich, Igor himself led the Polovtsy Konchak and Kobyak on a campaign against Polotsk. Even earlier, Svyatoslav used the Polovtsy in a short war with the Suzdal prince Vsevolod. With their help, he also hoped to knock out Rurik Rostislavich, his co-ruler and rival, from Kyiv, but suffered a severe defeat, and Igor and Konchak fled from the battlefield along the river in the same boat.

In 1184, the Polovtsy attacked Kyiv at an unusual time - at the end of winter. In pursuit of them, the Kyiv co-rulers sent their vassals. Svyatoslav sent Prince Igor Svyatoslavich of Novgorod-Seversky, and Rurik sent Prince Vladimir Glebovich of Pereyaslavl. Torkov was led by their leaders - Kuntuvdy and Kuldur. The thaw confused the plans of the Polovtsians. The overflowing river Khiriya cut off the nomads from the steppe. Here Igor overtook them, who on the eve refused the help of the Kyiv princes so as not to share the booty, and, as a senior, forced Vladimir to turn home. The Polovtsy were defeated, and many of them drowned, trying to cross the raging river.

In the summer of the same year, the Kyiv co-rulers organized a large campaign in the steppe, gathering ten princes under their banners, but no one from the Olgovichi joined them. Only Igor hunted somewhere on his own with his brother and nephew. The senior princes descended with the main army along the Dnieper in nasads (courts), and a detachment of squads of six young princes under the command of Prince Vladimir of Pereyaslav, reinforced by two thousand Berendeys, moved along the left bank. Kobyak, mistaking this vanguard for the entire Russian army, attacked him and found himself in a trap. On July 30, he was surrounded, captured and later executed in Kyiv for his many perjuries. The execution of a noble captive was unheard of. This aggravated relations between Russia and the nomads. The Khans swore revenge.

In February of the following year, 1185, Konchak approached the borders of Russia. The seriousness of the Khan's intentions was evidenced by the presence in his army of a powerful throwing machine for the assault on large cities. Khan hoped to use the split among the Russian princes and entered into negotiations with the Chernigov prince Yaroslav, but at that time he was discovered by Pereyaslav intelligence. Quickly gathering their rati, Svyatoslav and Rurik suddenly attacked Konchak's camp and scattered his army, capturing the stone-thrower that the Polovtsy had, but Konchak managed to escape.

Svyatoslav was not satisfied with the results of the victory. The main goal was not achieved: Konchak survived and continued to hatch plans for revenge at large. The Grand Duke decided to go to the Don in the summer, and therefore, as soon as the roads dried up, he went to collect troops in Korachev, and to the steppe - for cover or reconnaissance - he sent a detachment under the command of the governor Roman Nezdilovich, who was supposed to divert the attention of the Polovtsy and thereby help Svyatoslav to win time. After the defeat of Kobyak, it was extremely important to consolidate last year's success. There was an opportunity for a long time, as under Monomakh, to secure the southern border, inflicting a defeat on the second, main grouping of the Polovtsians (the first was led by Kobyak), but these plans were violated by an impatient relative.

Igor, having learned about the spring campaign, expressed an ardent desire to take part in it, but was unable to do so because of the heavy mud. Last year, he, his brother, nephew and eldest son went to the steppe at the same time as the Kyiv princes and, taking advantage of the fact that the Polovtsian forces were diverted to the Dnieper, captured some booty. Now he could not reconcile himself to the fact that the main events would take place without him, and, knowing about the raid of the Kyiv governor, he hoped to repeat last year's experience. But it turned out differently.

The army of the Novgorod-Seversky princes, who intervened in matters of grand strategy, turned out to be one on one with all the forces of the Steppe, where, no worse than the Russians, they understood the importance of the coming moment. It was prudently lured into a trap by the Polovtsians, surrounded, and after heroic resistance on the third day of the battle, it was almost completely destroyed. All the princes survived, but were captured, and the Polovtsy expected to receive a large ransom for them.

The Polovtsians were not slow to use their success. Khan Gza (Gzak) attacked the cities located along the banks of the Seim; he managed to break through the outer fortifications of Putivl. Konchak, wanting to avenge Kobyak, went west and laid siege to Pereyaslavl, which found itself in a very difficult situation. The city was saved by Kyiv aid. Konchak released the prey, but, retreating, captured the town of Rimov. Khan Gza was defeated by Svyatoslav's son Oleg.

The Polovtsian raids, mainly on Porosie (a region along the banks of the Ros River), alternated with Russian campaigns, but due to heavy snows and frosts, the winter campaign of 1187 failed. Only in March, voivode Roman Nezdilovich with "black hoods" made a successful raid beyond the Lower Dnieper and captured the "vezh" at a time when the Polovtsians went on a raid on the Danube.

The fading of the Polovtsian power

By the beginning of the last decade of the XII century. the war between the Polovtsians and the Russians began to subside. Only the merchant Khan Kuntuvdy, offended by Svyatoslav, having defected to the Polovtsy, was able to cause several small raids. In response to this, Rostislav Rurikovich, who ruled in Torchesk, twice made, although successful, but unauthorized campaigns against the Polovtsy, which violated the barely established and still fragile peace. The elderly Svyatoslav Vsevolodovich had to correct the situation and “close the gates” again. Thanks to this, the Polovtsian revenge failed.

And after the death of the Kyiv prince Svyatoslav, which followed in 1194, the Polovtsians were drawn into a new series of Russian strife. They participated in the war for the Vladimir inheritance after the death of Andrei Bogolyubsky and robbed the Church of the Intercession on the Nerl; repeatedly attacked the Ryazan lands, although they were often beaten by the Ryazan prince Gleb and his sons. In 1199, for the first and last time, the Vladimir-Suzdal prince Vsevolod Yuryevich Big Nest took part in the war with the Polovtsy, who went with the army to the upper reaches of the Don. However, his campaign was more like a demonstration of Vladimir's strength to the obstinate people of Ryazan.

At the beginning of the XIII century. Volyn prince Roman Mstislavich, the grandson of Izyaslav Mstislavich, distinguished himself in actions against the Polovtsy. In 1202, he overthrew his father-in-law, Rurik Rostislavich, and, as soon as he became the Grand Duke, he organized a successful winter campaign in the steppe, freeing many Russian captives captured earlier during the strife.

In April 1206, a successful raid against the Polovtsy was made by the Ryazan prince Roman "with his brethren." He captured large herds and freed hundreds of captives. This was the last campaign of the Russian princes against the Polovtsians. In 1210, they again robbed the surroundings of Pereyaslavl, taking "a lot of full", but also for the last time.

The most high-profile event of that time on the southern border was the capture by the Polovtsy of Pereyaslavl Prince Vladimir Vsevolodovich, who had previously reigned in Moscow. Having learned about the approach of the Polovtsian army to the city, Vladimir came out to meet him and was defeated in a stubborn and hard battle, but still prevented the raid. More chronicles do not mention any hostilities between the Russians and the Polovtsians, except for the continued participation of the latter in Russian strife.

The value of the struggle of Russia with the Polovtsy

As a result of a century and a half of armed confrontation between Russia and the Kipchaks, the Russian defense ground the military resources of this nomadic people, who were in the middle of the 11th century. no less dangerous than the Huns, Avars or Hungarians. This made it impossible for the Polovtsians to invade the Balkans, Central Europe or the Byzantine Empire.

At the beginning of the XX century. Ukrainian historian V.G. Lyaskoronsky wrote: “Russian campaigns in the steppe were carried out mainly due to the long-standing, through long experience of the conscious need for active actions against the steppe dwellers.” He also noted the differences in the campaigns of Monomashich and Olgovichi. If the princes of Kyiv and Pereyaslavl acted in the interests of all Russia, then the campaigns of the Chernigov-Seversky princes were carried out only for the sake of profit and fleeting glory. The Olgovichi had their own, special relationship with the Donetsk Polovtsians, and they even preferred to fight with them "in their own way", so as not to fall under Kiev influence in anything.

Of great importance was the fact that small tribes and individual clans of nomads were involved in the Russian service. They received the common name "black hoods" and usually faithfully served Russia, guarding its borders from their warlike relatives. According to some historians, their service was also reflected in some later epics, and the fighting techniques of these nomads enriched Russian military art.

The fight against the Polovtsy cost Russia many victims. Huge expanses of fertile forest-steppe outskirts were depopulated from constant raids. In some places, even in the cities, only the same service nomads remained - “houndsmen and Polovtsy”. According to historian P.V. Golubovsky, from 1061 to 1210, the Kipchaks made 46 significant trips to Russia, 19 of them - to the Principality of Pereyaslav, 12 - to Porosie, 7 - to the Seversk land, 4 each - to Kyiv and Ryazan. The number of small attacks cannot be counted. The Polovtsy seriously undermined Russian trade with Byzantium and the countries of the East. However, without creating a real state, they were not able to conquer Russia and only robbed it.

The struggle against these nomads, which lasted for a century and a half, had a significant impact on the history of medieval Russia. The well-known modern historian V.V. Kargalov believes that many phenomena and periods of the Russian Middle Ages cannot be considered without taking into account the “Polovtsian factor”. The mass exodus of the population from the Dnieper region and all of Southern Russia to the north largely predetermined the future division of the ancient Russian people into Russians and Ukrainians.

The struggle against the nomads for a long time preserved the unity of the Kievan state, "reviving" it under Monomakh. Even the course of the isolation of the Russian lands largely depended on how protected they were from the threat from the south.

The fate of the Polovtsy, who from the XIII century. began to lead a settled way of life and adopt Christianity, similar to the fate of other nomads who invaded the Black Sea steppes. A new wave of conquerors - the Mongol-Tatars - swallowed them up. They tried to resist the common enemy along with the Russians, but were defeated. The surviving Polovtsians became part of the Mongol-Tatar hordes, while all those who resisted were exterminated.

Internecine wars of Russian princes of the XI-XIII centuries

Russia was great and powerful in the time of St. Vladimir and Yaroslav the Wise, but the inner world, which was established under Vladimir and not without difficulty saved by his successor, was, alas, not for long. Prince Yaroslav gained his father's throne in a fierce internecine struggle. With this in mind, he prudently drew up a will, in which he clearly and clearly defined the inheritance rights of his sons, so that the troubled times of the first years of his reign would not be repeated in the future. The Grand Duke gave the entire Russian land to his five sons, dividing it into “destinies” and determining which of the brothers to reign in which. The eldest son Izyaslav received the Kyiv and Novgorod lands with both capitals of Russia. The next in seniority, Svyatoslav, reigned in the lands of Chernigov and Murom, which stretched from the Dnieper to the Volga along the Desna and Oka; he also got distant Tmutarakan, which had long been associated with Chernigov. Vsevolod Yaroslavich inherited the Pereyaslav land bordering the steppe - the "golden mantle of Kyiv", as well as the distant Rostov-Suzdal land. Vyacheslav Yaroslavich was content with a modest throne in Smolensk. Igor began to rule in Volhynia and in Carpathian Rus. In the Polotsk land, as during the life of Yaroslav, the cousin of the Yaroslavichs, Vseslav Bryachislavich, remained to reign.

As conceived by Yaroslav the Wise, this division did not at all mean the disintegration of Russia into separate possessions. The brothers received their reigns rather as governorships, for a while, and had to honor their elder brother Izyaslav, who inherited the great reign, "in his father's place." Nevertheless, the brothers together had to observe the unity of the Russian land, protect it from alien enemies and stop attempts at internecine strife. Russia was then conceived by the Rurikoviches as their common patrimonial possession, where the eldest in the family, being the Grand Duke, acted as the supreme manager.

To their credit, the Yaroslavichi brothers lived for almost two decades, guided by their father's will, preserving the unity of the Russian land and protecting its borders. In 1072, the Yaroslavichi continued the legislative activities of their father. A number of laws under the general title "The Truth of the Yaroslavichs" supplemented and developed the articles of "Russian Truth" by Yaroslav the Wise. Blood feud was forbidden; the death penalty was sentenced only for especially serious crimes.

The Russian laws of that time did not know any corporal punishment or torture, which favorably differed from the orders in other countries of the Christian world. However, joint lawmaking turned out to be the last common cause of the three Yaroslavichs. A year later, Svyatoslav, weighed down by his position as the ruler of the inheritance, albeit not a small one, and having lost respect for his elder brother, by force took away the great reign from Izyaslav. The ill-fated Izyaslav left Russia and embarked on joyless wanderings around Europe in a futile search for support. He asked for help from both the German emperor and the Pope, lost his treasury in the lands of the Polish king, and only after the death of Svyatoslav in 1076 was he able to return to Russia. The soft-hearted Vsevolod Yaroslavich generously returned to his elder brother his rightful great reign, making amends for his former guilt before him: after all, he did not prevent Svyatoslav from trampling on his father's will. But for a short time Izyaslav Yaroslavich gained a great reign. There was no former calm in the Russian land: the nephews, princes Oleg Svyatoslavich and Boris Vyacheslavich, raised the sword against their uncle and the Grand Duke. In 1078, in the battle on Nezhatina Niva near Chernigov, Izyaslav defeated the rebels, but he himself fell in battle. Vsevolod became the Grand Duke, but all 15 years of his reign (1078-1093) passed in incessant internecine strife, the main culprit of which was the energetic and cruel Prince Oleg Svyatoslavich, who received the nickname Gorislavich.

But is it really only the evil will of the son of Svyatoslav and similar seditious people that caused bloody unrest in Russia? Of course not. The trouble was nesting in the very Yaroslavl specific system, which could no longer satisfy the overgrown family of Rurikovich. There was no clear, precise order either in the distribution of inheritances or in their inheritance. Each branch of the clan - Izyaslavichi, Svyatoslavichi, Igorevichi, etc. - could consider itself infringed and demand a redistribution of principalities in its favor. No less confusing was the inheritance law. According to the old custom, the eldest in the family was supposed to inherit the reign, but along with Christianity, Byzantine law also comes to Russia, recognizing the inheritance of power only for direct offspring: the son must inherit the father, bypassing other relatives, even older ones. The inconsistency of hereditary rights, the uncertainty and confusion of destinies - this is the natural breeding ground that brought up Oleg Gorislavich and many others like him.

The bloody misfortunes of the Russian land, which originated from civil strife, were aggravated by the incessant raids of the Polovtsy, who skillfully used the strife of the Russian princes to their advantage. Other princes themselves, taking the Polovtsy as allies, brought them to Russia.

Gradually, many princes changed their minds and began to look for a way to end the strife. A particularly prominent role in this belonged to the son of Vsevolod Yaroslavich, Vladimir Monomakh. At his suggestion, in 1097 the princes gathered in Lyubech for the first princely congress. This congress was considered by Monomakh and other princes as a means that would allow reaching a common agreement and finding a way to prevent further civil strife. At it, the most important decision was made, which read: "Let everyone keep his fatherland." These simple words carried great meaning. "Fatherland" is a hereditary possession passed from father to son. Thus, each prince turned from a governor, always ready to leave his inheritance for the sake of a more honorable reign, into its permanent and hereditary owner. The consolidation of appanages as immediate fathers was intended to satisfy all the warring branches of the vast family of Rurikovich, to bring proper order into the appanage system. Being now confident in their rights to hereditary possessions, the princes should have stopped their former enmity. The organizers of the Lyubech princely congress were counting on this.

It really became a turning point in Russian history, for it marked a turning point in the distribution of land ownership in Russia. If earlier the Russian land was a common tribal possession of all the Rurikovichs, which was controlled by the Grand Duke, now Russia was turning into a collection of hereditary princely possessions. Since that time, the princes in their principalities are no longer governors by the will of the Grand Duke, as has been customary since the time of St. Vladimir, but full-fledged masters-rulers. The power of the Kyiv prince, who thus lost his former right to distribute destinies-governors throughout the Russian land, inevitably lost its all-Russian significance. Thus, Russia entered a historical period, the most important feature of which was political fragmentation. Many countries of Europe and Asia went through this period to one degree or another.

But Russia did not find itself in a state of fragmentation immediately after the Lyubech Congress. The need to unite all forces against the Polovtsian danger and the mighty will of Vladimir Monomakh postponed the inevitable for a while. In the first decades of the XII century. Russia goes on the offensive against the Polovtsy, inflicting crushing defeats on them. During the reign in Kyiv of Vladimir Monomakh (1113-1125) and his son Mstislav the Great (1125-1132), it seemed that the times of St. Vladimir and Yaroslav the Wise returned. Again, united and mighty Russia victoriously crushes its enemies, and the Grand Duke from Kyiv vigilantly keeps order in the Russian land, mercilessly punishing the rebellious princes ... But Monomakh died, Mstislav passed away, and from 1132, as it is said in the chronicle, the whole Russian land. The former appanages, having become hereditary "fatherlands", gradually turn into independent principalities, almost independent states, the rulers of which, in order to elevate themselves on a par with the princes of Kyiv, also begin to be called "great princes".

In the middle of the XII century. civil strife reached an unprecedented severity, and the number of their participants increased many times due to the fragmentation of princely possessions. At that time in Russia there were 15 principalities and separate lands; in the next century, on the eve of the Batu invasion, there were already 50, and during the reign of Ivan Kalita, the number of principalities of various ranks exceeded two and a half hundred. Over time, they became smaller, split up among the heirs and weakened. No wonder it was said that "in the Rostov land, seven princes have one warrior, and in every village - a prince." The growing male generation demanded separate possessions from their fathers and grandfathers. And the smaller the principalities became, the more ambition and claims appeared among the owners of new destinies: every "ruling" prince sought to seize a "piece" fatter, presenting all conceivable and inconceivable rights to the lands of his neighbors. As a rule, civil strife went for a larger territory or, in extreme cases, a more “prestigious” principality. A burning desire to exalt and pride, which comes from the consciousness of their own political independence, pushed the princes to a fratricidal struggle, during which continuous hostilities divided and devastated the Russian lands.

after the death of Mstislav the Great, one principality after another falls away from Kyiv. In 1135, many years of strife began in Southern Russia: then from the distant Rostov-Suzdal land will appear

Yuri Vladimirovich Dolgoruky and capture the Principality of Pereyaslavl, then the Chernigov prince Vsevolod Olgovich will appear with the Polovtsy dear to him, "villages and cities are fighting ... and people are cutting."

The year 1136 was marked by a real political upheaval in Novgorod the Great: Prince Vsevolod Mstislavich was accused by the "men of Novgorod" of cowardice, a negligent attitude towards the defense of the city, and also that a year earlier he wanted to change Novgorod to the more honorable Pereyaslavl. For two months, the prince, his children, wife and mother-in-law were in custody, after which they were expelled. Since that time, the Novgorod boyars themselves began to invite princes to themselves and finally freed themselves from the power of Kyiv.

The main opponent of the Rostov-Suzdal prince at that time, Volyn prince Izyaslav Mstislavich, in one of his letters to the Hungarian king gave a vivid political description of Dolgoruky: “Prince Yuri is strong, and Davydovichi and Olgovichi (strong princely branches of the house of Rurikovich. - Note. ed.) the essence is with him, and the wild Polovtsians are with him, and he brings those with gold. Beginning in 1149, Dolgoruky occupied the throne of Kyiv three times. In turn, Prince Izyaslav, who was in alliance with the Smolensk princes and often resorted to the help of mercenaries from Poland and Hungary, sought to expel Yuri from Kyiv with no less persistence. The devastating war went on with varying success, Kyiv and Kursk, Pereyaslavl and Turov, Dorogobuzh, Pinsk and other cities passed from hand to hand. The Kievans, like the Novgorodians, tried to play on the contradictions between the princes, trying to preserve the rights of self-government and the independence of their city. However, they did not always succeed.

The denouement of a long-term drama came in 1154, when, one after another, another co-rulers of Kyiv and the Kyiv land, Izyaslav Mstislavich and his uncle Vyacheslav, went into the world. The following year, Yuri Dolgoruky turned to Izyaslav Davydovich, who reigned in Kyiv, with the words: “Kyiv is my fatherland, not you.” According to the chronicle, Izyaslav prudently answered the formidable opponent, "begging him and bowing": "Do not harm me, but here is Kyiv for you." Dolgoruky occupied the city. Finally, he ended up on the coveted "table of his fathers and grandfathers, and the whole Russian land accepted him with joy," the chronicler claimed. By the way the people of Kiev reacted to the unexpected death of Yuri after the feast at the Kyiv boyar Petrila (the townspeople did not leave stone unturned from the country and city estates of the prince), we can safely conclude that the chronicler was cunning, convincing the reader that Yuri was met "with joy great and honoured."

Yuri's son and successor Andrei Bogolyubsky moved his capital to Vladimir-on-Klyazma and changed his political orientation. Civil strife flared up with renewed vigor, but the main thing for the strongest Russian prince was not the possession of Kyiv, but the strengthening of his own principality; South Russian interests fade into the background for him, which turned out to be disastrous for Kyiv politically.

In 1167-1169. Volyn Prince Mstislav Izyaslavich reigned in Kyiv. Andrei Bogolyubsky started a war with him and at the head of eleven princes approached the city. Mstislav Izyaslavich fled to Volhynia, to Vladimir, and the victors robbed Kyiv for two days - “Podolia and Gora, and monasteries, and Sofia, and the Tithe Mother of God (i.e., districts and the main shrines of the city. - Note. ed.). And there was no mercy for anyone and nowhere. Churches were on fire, Christians were killed and others were bound, women were led into captivity, separated by force from their husbands, babies wept, looking at their mothers. And they seized a lot of property, and in churches they robbed icons, and books, and robes, and bells. And there were in Kyiv among all the people groaning and hardship, and inconsolable grief, and incessant tears. The ancient capital, "the mother of hail (cities. - Note. ed.) Russian”, finally lost its former greatness and power. In the coming years, Kyiv was ravaged twice more: first by the Chernigovites, and then by the Volyn princes.

In the 80s. restless XII century, the strife between the Russian princes subsided somewhat. It’s not that the rulers of Russia changed their minds, they were just busy in a continuous struggle with the Polovtsians. However, already at the very beginning of the new, XIII century, a great atrocity again happened in Russia. Prince Rurik Rostislavich, together with his Polovtsian allies, captured Kyiv and carried out a horrific rout there. The strife in Russia continued until the Batyev attack. Many princes and their deputies changed in Kyiv, much blood was shed in internecine strife. So, in fratricidal wars, busy with princely intrigues and strife, Russia did not notice the danger of a terrible foreign force that rolled in from the East, when the whirlwind of Batu's invasion almost wiped Russian statehood from the face of the earth.

Not much is known about the Polovtsian warriors, but contemporaries considered their military organization to be quite high for their time. All men capable of bearing arms were required to serve in the Polovtsian army. The military organization of the Polovtsy developed in stages. Byzantine historians note that the Polovtsian warriors fought with bows, darts and curved sabers. The quivers were worn on the side. According to the crusader Robert de Clari, the Kipchak warriors wore clothes made of sheep skins and each had 10-12 horses. The main force of the nomads, like any steppe dwellers, were detachments of light cavalry armed with bows. Polovtsian warriors, in addition to bows, also had sabers, lassoes and spears. Later, squads with heavy weapons appeared in the troops of the Polovtsian khans. Heavily armed warriors wore chain mail, lamellar shells and helmets with anthropomorphic iron or bronze masks and aventails. Experienced and well-armed warriors were called "koshchei" (from the word "kosh"). Each of them had a spare horse, as well as a servant. Nevertheless, detachments of lightly armed horse archers continued to remain the basis of the army. It is also known (since the second half of the 12th century) that the Polovtsians used heavy crossbows and “liquid fire”, borrowed, perhaps, from China since their time in the Altai region, or in later times from the Byzantines. Using this technique, the Polovtsy were able to take well-fortified cities. The Polovtsian troops were distinguished by maneuverability, but often their speed of movement was greatly slowed down due to the bulky convoy, consisting of carts with luggage. Some carts were equipped with crossbows and were suitable for protection during enemy attacks. During sudden attacks by the enemy, the Polovtsy knew how to defend themselves stubbornly, surrounding their camp with wagons. The Polovtsy used the tactics of surprise attacks, feigned retreats and ambushes, traditional for nomads. They acted mainly against weakly defended villages, rarely attacking fortified fortresses. In a field battle, the Polovtsian khans competently divided forces, used flying detachments in the forefront to start a battle, which were then reinforced by an attack by the main forces. As an excellent military school, where the Polovtsy honed their skills in maneuvering, the Polovtsy served as a round hunt. However, the insufficient number of professional soldiers often led to the defeat of the Polovtsian armies.