Fable definition. "fable as a literary genre"

A fable is a short story, most often in verse, mostly of a satirical nature. A fable is an allegorical genre, therefore, moral and social problems are hidden behind the story about fictional characters (most often about animals).

The emergence of the fable as a genre dates back to the 5th century BC, and the slave Aesop (VI-V centuries BC) is considered its creator, who was unable to express his thoughts in a different way. This allegorical form of expressing one's thoughts was subsequently called the "Aesopian language". Only around the 2nd century BC. e. fables began to be written down, including Aesop's fables. In ancient times, the famous fabulist was the ancient Roman poet Horace (65–8 BC).

In the literature of the 17th-18th centuries, ancient subjects were processed.

In the 17th century, the French writer La Fontaine (1621–1695) revived the fable genre again. Many of the fables of Jean de La Fontaine are based on the plot of Aesop's fables. But the French fabulist, using the plot of an ancient fable, creates a new fable. Unlike ancient authors, he reflects, describes, comprehends what is happening in the world, and does not strictly instruct the reader. Lafontaine focuses more on the feelings of his characters than on moralizing and satire.

In 18th-century Germany, the poet Lessing (1729–1781) turned to the fable genre. Like Aesop, he writes fables in prose. For the French poet Lafontaine, the fable was a graceful short story, richly ornamented, "a poetic toy." It was, in the words of Lessing's fable, a hunting bow, so beautifully carved that it lost its original purpose, becoming the decoration of the living room. Lessing declares literary war on Lafontaine: "The narrative in the fable," he writes, "...should be compressed to the utmost; deprived of all ornaments and figures, she must be content with clarity alone" ("Abhandlungen uber die Fabel" - Discourses on the fable , 1759).

In Russian literature, the foundations of the national fable tradition were laid by A.P. Sumarokov (1717–1777). His poetic motto was the words: "As long as I do not fade with decrepitude or death, I will not stop writing against vices ...". The fables of I.A. Krylov (1769–1844), which absorbed the experience of two and a half millennia, became the pinnacle in the development of the genre. In addition, there are ironic, parodic fables of Kozma Prutkov (A.K. Tolstoy and the Zhemchuzhnikov brothers), revolutionary fables of Demyan Bedny. The Soviet poet Sergei Mikhalkov, whom young readers know as the author of "Uncle Styopa", revived the fable genre, found his own interesting style of modern fable.

One of the features of fables is allegory: a certain social phenomenon is shown through conditional images. So, behind the image of Leo, traits of despotism, cruelty, injustice are often guessed. The fox is a synonym for cunning, lies and deceit.

It should be noted such features of the fable:

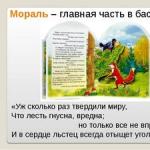

a) morality;

b) allegorical (allegorical) meaning;

c) the typicality of the described situation;

d) characters-characters;

e) ridicule of human vices and shortcomings.

V.A. Zhukovsky in the article "On the fable and fables of Krylov" pointed out four main features of the fable.

First fable feature - character traits, then how one animal differs from another: “Animals represent a person in it, but a person is only in some respects, with some properties, and each animal, having with it its inalienable permanent character, is, so to speak, ready and clear for everyone an image of both a person and a character that belongs to him. You make a wolf act - I see a bloodthirsty predator; bring a fox onto the stage - I see a flatterer or a deceiver ... ". So, the Donkey personifies stupidity, the Pig - ignorance, the Elephant - sluggishness, the Dragonfly - frivolity. According to Zhukovsky, the task of a fable is to help the reader understand a difficult everyday situation using a simple example.

Second feature of the fable, writes Zhukovsky, is that "transferring the reader's imagination to new dreamy world, you give him the pleasure of comparing the fictional with the existing (which the first serves as a likeness), and the pleasure of comparison makes morality itself attractive. "That is, the reader may find himself in an unfamiliar situation and live it together with the characters.

Third feature of the fable moral lesson, morality condemning the character's negative quality. "There is a fable moral lesson which you give to man with the help of cattle and inanimate things; presenting to him as an example creatures that are different from him by nature and completely alien to him, you spare his vanity, you force him to judge impartially, and he insensitively pronounces a severe sentence on himself," writes Zhukovsky.

Fourth feature - instead of people in the fable, objects and animals act. "On the stage on which we are accustomed to seeing a person acting, you bring out with the power of poetry such creations that are essentially removed from it by nature, miraculousness, just as pleasant for us as in the epic poem the action of supernatural forces, spirits, sylphs, gnomes and the like. The strikingness of the miraculous is communicated in a certain way to the morality that is hidden under it by the poet; and the reader, in order to reach this morality, agrees to accept the miraculousness itself as natural.

the fable of the crow and the fox, the fable of the dragonfly and the ant

Fable- a poetic or prose literary work of a moralizing, satirical nature. at the end or at the beginning of the fable there is a brief moralizing conclusion - the so-called morality. The actors are usually animals, plants, things. The fable ridicules the vices of people. The fable is one of the oldest literary genres. Ancient Greece was famous for Aesop (VI-V centuries BC), who wrote fables in prose. Rome - Phaedrus (1st century AD). In India, the Panchatantra collection of fables dates back to the 3rd century. The most prominent fabulist of modern times was the French poet Jean La Fontaine (XVII century).

In Russia, the development of the fable genre dates back to the middle of the 18th - early 19th centuries and is associated with the names of A.P. Sumarokov, I.I. Khemnitser, A.E. Izmailov, I.I. century by Simeon of Polotsk and in the first half of the 18th century by A. D. Kantemir, V. K. Trediakovsky. Russian poetry develops a fable free verse, conveying the intonations of a laid-back and crafty tale.

The fables of I. A. Krylov, with their realistic liveliness, sensible humor and excellent language, marked the heyday of this genre in Russia. During the Soviet era, the fables of Demyan Bedny, Sergei Mikhalkov and others gained popularity.

- 1. History

- 1.1 Origin

- 1.2 Antiquity

- 1.2.1 Greek literature

- 1.2.2 Rhetoric

- 1.2.3 Roman literature

- 1.3 Middle Ages

- 1.4 Revival

- 2 Fable in Russian literature

- 3 Animal fables

- 4 Fabulists

- 5 See also

- 6 Notes

- 7 Literature

- 8 Links

History

Origin

There are two theories about the origin of the fable. The first is represented by the German school of Otto Crusius, A. Hausrath, and others, the second by the American scientist B. E. Perry. According to the first concept, the story is primary in the fable, and morality is secondary; the fable comes from the animal tale, and the animal tale comes from the myth. According to the second concept, morality is primary in a fable; the fable is close to comparisons, proverbs and sayings; like them, the fable emerges as an aid to argumentation. The first point of view goes back to the romantic theory of Jacob Grimm, the second one revives Lessing's rationalistic concept.

Philologists of the 19th century were long occupied with the controversy about the priority of the Greek or Indian fable. Now it can be considered almost certain that the common source of the material of the Greek and Indian fable was the Sumero-Babylonian fable.

Antiquity

Greek literature

Before the fable became an independent literary genre, in its development it passed through the stage of an instructive example or parable, and then folklore. Only two specimens have survived from the earliest stage. These are the famous parable (αινος) of Odysseus (Od. XIV, 457-506) and the two parables exchanged between Teucer and Menelaus in Sophocles' Ayantha (v. 1142-1158).

The prevailing form of the oral fable, corresponding to the second period of the development of the genre, we find for the first time in Greek literature in Hesiod. This is the famous parable (αινος) about the nightingale and the hawk (“Works and Days”, 202-212), addressed to cruel and unjust rulers. In the parable of Hesiod, we already meet all the signs of the fable genre: animal characters, action outside of time and space, sententious morality in the mouth of a hawk.

Greek poetry of the 7th-6th centuries BC. e. known only in scarce passages; some of these passages in separate images echo the fable plots known later. This allows us to assert that the main fable plots of the classical repertoire had already developed by this time in folk art. in one of his poems, Archilochus (ref. 88-95 B) mentions a “parable” about how an eagle offended a fox and was punished for it by the gods; in another poem (ref. 81-83 B) he tells a "parable" about a fox and a monkey. Aristotle attributes to Stesichorus a speech to the citizens of Himera with a fable about a horse and a deer in relation to the threat of the tyranny of Falaris (Rhetoric, II, 20, 1393b). The Carian parable of the fisherman and the octopus, according to Diogenian, was used by Simonides of Ceos and Timocreon. The fabled form appears quite distinctly in the anonymous scolius about the snake and cancer given by Athenaeus (XV, 695a).

Greek literature of the classical period already relies on a well-established tradition of oral fable. Herodotus introduced the fable into historiography: Cyrus instructs the Ionians who obeyed too late with a “fable” (logos) about a fisherman-flute player (I, 141). Aeschylus used the fable in tragedy: a passage has been preserved outlining the "glorious Libyan fable" (logos) about an eagle struck by an arrow with eagle feathers. In Aristophanes, Pisfeter, in a conversation with birds, brilliantly argues with Aesop's fables about a lark who buried his father in his own head ("Birds", 471-476) and about a fox offended by an eagle ("Birds", 651-653), and Trigey refers to a fable in an explanation of his flight on a dung beetle (“The World”, 129-130), and the entire final part of the comedy “The Wasps” is built on playing out fables inappropriately used by Philokleon.

Democritus commemorates the "Aesopian dog", which was destroyed by greed (ref. 224 D.); close to this genre are Prodicus in his famous allegory of Hercules at the crossroads (Xenophon, "Memories of Socrates", II, 1) and Protagoras in his fable (mythos) about the creation of man (Plato, "Protagoras", 320 ff.); Antisthenes refers to the fable of lions and hares (Aristotle, "Politics", III, 8, 1284a, 15); his student Diogenes composes the dialogues "Leopard" and "Jackdaw" (Diog. Laertes., VI, 80). Socrates in Xenophon tells a fable about a dog and sheep (“Memoirs”, II, 7, 13-14), in Plato he recalls that a fox said “in Aesop’s fable” (mythos) to a sick lion about the tracks leading to his cave (“ Alcibiades I", 123a), and even composes in imitation of Aesop a fable about how nature inextricably linked suffering with pleasure ("Phaedo", 60c). Plato even claims that Socrates, who never composed anything, shortly before his death transcribed the Aesopian fables into verse (Phaedo, 60s) - a story clearly fictional, but willingly accepted by descendants (Plutarch, How to Listen to Poets, 16s; Diog. Laertes, II, 42).

Rhetoric

At the turn of the classical and Hellenistic eras, from "high" literature, the fable descends into educational literature intended for children, and into popular literature, addressed to an uneducated grassroots public. The fable becomes the monopoly of schoolteachers and philosophical preachers. This is how the first collections of fables appear (for the needs of teaching), and the third period in the history of the fable genre in antiquity begins - the period of transition from oral to literary fable. The first collection of Aesopian fables that has come down to us is the Logon Aisopeion Synagoge by Demetrius of Phaler, compiled at the turn of the 4th and 3rd centuries BC. e. Demetrius of Phaler was a peripatetic philosopher, a student of Theophrastus; in addition, he was an orator and theoretician of eloquence. The collection of Demetrius, apparently, served as the basis and model for all later recordings of fables. Even in the Byzantine era, fable collections were published under his name.

Collections of such records were, first of all, raw material for school rhetorical exercises, but soon ceased to be the exclusive property of the school and began to be read and copied like real "folk books". Later manuscripts of such collections have come down to us in very large numbers under the conditional name of "Aesop's fables." Researchers distinguish among them three main reviews (editions):

- the oldest, the so-called Augustan, apparently dates back to the 1st-2nd centuries AD. e., and written in everyday koine of that time;

- the second, the so-called Vienna, refers to the VI-VII centuries and reworks the text in the spirit of folk vernacular;

- the third, the so-called Akkursievskaya, which breaks up into several sub-reviews, was created during one of the Byzantine Renaissance (according to one opinion - in the 9th century, according to another - in the 14th century) and reworked in the spirit of Atticism, fashionable in the then literature.

The Augustan edition is a collection of more than two hundred fables, all of which are more or less homogeneous in type and cover the range of fable plots that later became the most traditional. The writing of the fables is simple and brief, limited to conveying the plot basis without any minor details and motivations, tending to stereotypical formulas for repetitive plot points. Separate collections of fables vary greatly both in composition and in wording.

In the rhetorical school, the fable took a firm place among the “progymnasm” - preparatory exercises with which the training of the rhetor began. The number of pro-gymnasms ranged from 12 to 15; in the finally established system, their sequence was as follows: fable, story, hriya, maxim, refutation and affirmation, common place, praise and censure, comparison, etopoeia, description, analysis, statute. The fable, among other simple progymnasms, was apparently originally taught by a grammarian and only then passed into the hands of a rhetorician. Special textbooks containing theoretical characteristics and samples of each type of exercise served as a manual for the study of progymnasm. Four such textbooks have come down to us, belonging to the rhetors Theon (end of the 1st - beginning of the 2nd century AD), Hermogenes (2nd century), Aphtonius (4th century) and Nicholas (5th century), as well as extensive comments on them, compiled already in the Byzantine era, but based on materials from the same ancient tradition (the commentary on Aphtonius, compiled by Doxopater, XII century, is especially rich in material). The general definition of a fable, unanimously accepted by all progymnasmatics, reads: “A fable is a fictional story that is an image of the truth” (mythes esti logos pseudes, eikônizôn aletheian). The moral in the fable was defined as follows: "This is a maxim (logos) added to the fable and explaining the useful meaning contained in it." The moral at the beginning of the fable is called the promythium; the moral at the end of the fable is the epimyth.

The place of the fable among other forms of argumentation was outlined by Aristotle in Rhetoric (II, 20, 1393a23-1394a 18). Aristotle distinguishes two ways of persuasion in rhetoric - an example (paradeigma) and an enthymema (enthymema), respectively, similar to induction and deduction in logic. The example is subdivided into a historical example and a fictional example; the fictional example is in turn subdivided into a parabola (that is, a conditional example) and a fable (that is, a concrete example). The development of a fable in theory and practice was closed within the walls of grammatical and rhetorical schools; fables did not penetrate into public oratory practice.

Roman literature

In Roman literature, in the "iambes" of Callimachus of Cyrene, we find two incidentally inserted fables. "Saturah" Ennius retold in verse the fable of the lark and the reaper, and his successor Lucilius - the fable of the lion and the fox. Horace cites fables about a field and city mouse (“Satires”, II, 6, 80-117), about a horse and a deer (“Messages”, I, 10, 34-38), about an overstuffed fox (“Messages”, I, 7, 29-33), about a frog imitating a bull (“Satires”, II, 3, 314-319), and about a fox imitating a lion (“Satires”, II, 3, 186), about a lion and a fox (“ Messages ”, I, 1, 73-75), about a jackdaw in stolen feathers (“Messages”, I, 3, 18-20), compares himself and his book with a drover and a donkey (“Messages”, I, 20, 14 -15), at the sight of a sly man he thinks of a crow and a fox ("Satires", II, 5, 55), at the sight of an ignoramus - about a donkey and a lyre ("Messages", II, 1, 199). At the turn of our era, the period of the formation of a literary fable begins.

In the literary fable, two opposite directions in the development of the fable genre were outlined: the plebeian, moralistic direction of Phaedrus (fable-satire) and the aristocratic, aesthetic direction of Babrius (fable-tale). All late Latin fable literature ultimately goes back to either Phaedrus or Babrius. Avian was the successor of the Babrian line of fable in Roman literature. The continuation of the Fedrov tradition was the late Latin collection of fables, known as "Romulus".

Middle Ages

The general cultural decline of the "dark ages" equally plunged both Avian and "Romulus" into oblivion, from where they were extracted by a new revival of medieval culture in the 12th century. Since that time, we find in medieval Latin literature no less than 12 revisions of Romulus and no less than 8 revisions of Avian.

- Apparently, around the 11th century, an edition known as "Nilantov Romulus"(named after the philologist I.F. Nilant, who first published this collection in 1709) of 50 fables; Christianization of morals is noticeable in places.

- Probably, at the beginning of the XII century, "Nilantov Romulus" was translated into English and supplemented with numerous plots of new European origin - fairy tales, legends, fablio, etc. - the authorship of the resulting collection was attributed to the famous king Alfred. This "English Romulus" not preserved.

- However, in the last third of the 12th century it was translated in verse into French by the Anglo-Norman poet Mary of France (under the title "Izopet") and in this form became widely known; and from the collection of Mary of France two back-translations into Latin were made.

- This is, firstly, the so-called "Expanded Romulus", a collection of 136 fables (79 fables from Romulus, 57 developing new plots), set out in great detail, in a rough fairy-tale style; the collection served as the basis for two German translations.

- Secondly, this is the so-called "Robert Romulus"(after the name of the original publisher, 1825), a collection of 22 fables, presented concisely, without any fabulous influence and with a claim to grace.

Two more poetic arrangements were made in the second half of the 12th century. Both arrangements are made in elegiac distich, but differ in style.

- The first of them contains 60 fables: the presentation is very rhetorically magnificent, replete with antitheses, annominations, parallelisms, etc. This collection was very popular until the Renaissance (more than 70 manuscripts, 39 editions only in the 15th century) and was translated more than once into French, German and Italian (among these translations is the famous "Isopetus of Lyon"). The author's name was not indicated; since 1610, when Isaac Nevelet included this collection in his edition of Mythologia Aesopica, the designation Anonymous Neveleti.

- The second collection of poetic arrangements of "Romulus" was compiled somewhat later; its author is Alexander Neckam. His collection is titled "New Aesop" and consists of 42 fables. Neckam writes more simply and sticks closer to the original. At first, Neckam's collection was a success, but it was soon completely eclipsed by Anonymus Neveleti, and it remained in obscurity until the 19th century.

Fables were extracted from Romulus and inserted into the Historical Mirror by Vincent of Beauvais (XIII century) - the first part of a huge medieval encyclopedia in 82 books. Here (IV, 2-3), the author, having reached in his presentation to “the first year of the reign of King Cyrus”, reports that this year the fabulist Aesop died in Delphi, and on this occasion sets out 29 fables in 8 chapters. These fables, says the author, can be successfully used in the preparation of sermons.

In some manuscripts, the fables of "Romulus" are joined by the so-called fabulae extravagantes - fables of unknown origin, set out in a very popular language, in detail and colorfully, and approaching the type of an animal tale.

- Of the two prose paraphrases of Avian, one is without a title, the other is indicated as Apologi Aviani.

- Three poetic paraphrases are titled "New Avian", are made in elegiac distichs and date back to the 12th century. The author of one of the paraphrases calls himself vates Astensis (“poet from Asti”, a city in Lombardy). Another one belongs again to Alexander Neckam.

rebirth

During the Renaissance, the spreading knowledge of the Greek language gave the European reader access to the primary source - to the Greek fables of Aesop. Since 1479, when the Italian humanist Accursius published the first printed edition of Aesop's fables, the development of a new European fable begins.

Fable in Russian literature

The fable penetrated into Russian literature several centuries ago. Already in the XV-XVI centuries, fables that came through Byzantium from the East were popular. Later, the fables of Aesop became known, whose biographies were in great circulation in the 17th and 18th centuries (lubok books).

In 1731, Antiochus Cantemir wrote, imitating Aesop, six fables. Also, Vasily Tredyakovsky, Alexander Sumarokov performed fables (the first gave imitations of Aesop, the second - translations from La Fontaine and independent fables).

The fables of Ivan Khemnitser (1745-84), who translated La Fontaine and Christian Gellert, but also wrote independent fables, become artistic; Ivan Dmitriev (1760-1837), who translated the French: La Fontaine, Florian, Antoine de Lamotte, Antoine Vincent Arnault, and Alexander Izmailov (1779-1831), most of whose fables are independent. Izmailov's contemporaries and the generation closest to him greatly appreciated his fables for their naturalness and simplicity, giving the author the name of "Russian Tenier" and "Krylov's friends."

The fable of Ivan Andreevich Krylov (1768-1844), translated into almost all Western European and some Eastern languages, reached brilliant perfection. Translations and imitations occupy a completely inconspicuous place with him. For the vast majority of their parts, Krylov's fables are quite original. Krylov still had support in his work in the fables of Aesop, Phaedrus, La Fontaine. Having reached its highest limit, the fable after Krylov disappears as a special kind of literature, and remains only in the form of a joke or a parody.

fable animals

Animal fables are fables in which animals (wolf, owl, fox) act as a person. The fox is cunning, the owl is wisdom. The goose is considered stupid, the lion - courageous, the snake - insidious. The qualities of fairy animals are interchangeable. Fairy animals represent certain characteristic features of people.

The moralized natural science of ancient animal fables eventually took shape in collections known under the title of "Physiologist".

fabulists

- Jean de La Fontaine

- I. A. Krylov

- Demyan Bedny

- Olesya Emelyanova

- Vasily Maykov

- Avian

- Babriy

- Sergei Mikhalkov

- Alexander Sumarokov

- Ivan Dmitriev

- Ludwig Holberg

- Grigory Savvich Skovoroda

- Pyotr Gulak-Artemovsky

- Levko Borovikovsky

- Evgeniy Grebyonka

- Leonid Glibov

- L. N. Tolstoy

- David Sedaris (English) Russian

see also

- Apologist

- Parable

- Allegory

Notes

- FEB: Eiges. Fable // Dictionary of literary terms. T. 1. - 1925 (text)

- "Squirrel Seeks Chipmunk"

Literature

- Gasparov M. L. Antique literary fable. - M., 1972.

- Grintser P. A. On the question of the relationship between ancient Indian and ancient Greek fables. - Grintser P. A. Selected works: 2 vols. - M .: RGGU, 2008. - T. T. 1. Ancient Indian literature. - S. 345-352.

Links

- Fable // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.

- Fables on "Parables and Tales of East and West"

the fable of the wolf and the lamb, the fable of the crow and the fox, the fable of the quartet, the fable of Krylov, the fable of the swan, cancer and pike, the fable of the fly, the fable of the pig under the oak, the fable of the elephant and the pug, the fable of the dragonfly and the ant, this fable

Fable Information About

Fable as a literary genre

Potapushkina Natalya Vladimirovna

What is a fable? Features of the fable.

Fable- one of the oldest literary genres, a short entertaining story in verse or prose with an obligatory moralizing conclusion.

Purpose of the fable: ridicule of human vices, shortcomings of public life

Presence of morality(moral) at the beginning or end of a fable. Sometimes morality is only implied

The presence of an allegory: allegorical depiction of events, heroes

Animals are often the heroes.

Dialogue is often introduced, lending a touch of comedy

The language of the fable is predominantly colloquial

Origin of the fable

The fable acquires a stable genre form in Greek literature. The most prominent representative of this time is the semi-legendary Aesop (6th century BC). According to legend, he was a slave, had an ugly appearance and became a victim of deceit. His wisdom was legendary.

The fable genre has its roots in the folklore of many peoples.

Scientists attribute the first written signs of "fable" to the Sumero-Akkadian texts.

Aesopian language - cryptography in literature, allegory, deliberately masking the thought (idea) of the author.

Aesop's fables

Aesop's Fables is a collection of prose works containing at least 400 fables. Legends say that according to the wise collection of Aesopian fables, children were taught in the era of Aristophanes in Athens. What is special about the collection? The fact that the presentation of the texts is boring, without literary gloss, but extremely insightful. Therefore, for many centuries, many writers have sought to artistically translate these fables. Thanks to this, Aesopian stories have come down to us and have become clear to us.

In Russian, a complete translation of all Aesop's fables was published in 1968.

Genre difference and similarity of parable and fable

parable

fable

1. There are no clear genre boundaries: a fairy tale and a proverb can act as a parable.

1. Genre of satirical poetry.

2. The teaching is allegorical. The parable must be unraveled, experienced.

2. Has a clear conclusion - morality.

3. Characters are nameless, outlined schematically, devoid of characters.

3. Heroes - people, animals, plants - are carriers of certain character traits.

4. The point is that the moral choice is made by man.

4. Ridicule of social and human vices.

5. Prose form.

5. Usually a poetic form.

6. A short story.

7. Is instructive.

8. Uses allegory.

famous fabulists

I.A. Krylov

Jean La Fontaine

G.Lessing

V.K.Trediakovsky

A.Kantemir

S.V. Mikhalkov

A.P. Sumarokov

I.I. Dmitriev

Fable in Russian literature

The fable penetrated into Russian literature several centuries ago. Already in the XV-XVI centuries, fables that came through Byzantium from the East were popular. Later, the fables of Aesop became known, whose biographies were in great circulation in the 17th and 18th centuries (lubok books).

In 1731, Antiochus Cantemir wrote, imitating Aesop, six fables. Also, Vasily Tredyakovsky, Alexander Sumarokov performed fables (the first gave imitations of Aesop, the second - translations from La Fontaine and independent fables).

The fable of Ivan Andreevich Krylov (1768-1844), translated into almost all Western European and some Eastern languages, reached brilliant perfection. Having reached its highest limit, the fable after Krylov disappears as a special kind of literature, and remains only in the form of a joke or a parody.

Ivan Andreevich Krylov

(1769-1844)

Ivan Andreevich Krylov was born on February 13, 1769 in Moscow into the family of a retired officer. The family lived very poorly, and could not give a systematic education to the child. Very early, as a teenager, I.A. Krylov went to work. However, he stubbornly and a lot was engaged in self-education, studied literature, mathematics, French and Italian. At the age of 14, he first tried his hand at the literary field. However, his early comedies were not successful. In 1809, the first book of fables by I.A. Krylov was published, and from that moment real fame came to him.

Features of Krylov's fables

- proximity to the Russian folk tale

- lively and relaxed language

Among the predecessors of I.A. Krylov, the didactic moment - morality - dominated in the fable. I.A. Krylov created a fable-satire, a fable - a comedy scene. In contrast to the traditional schematism of the genre, the conditionally allegorical characters of Krylov's fables bear the real features of people; they are included by the writer in a wide panorama of Russian society, representing its various social strata - from the king to the shepherd.

The characters and sayings of I.A. Krylov's fables are organically woven into the fabric of modernity. Many lines of the works of I.A. Krylov became popular expressions. They still help to more accurately and vividly convey our impressions of the events of the surrounding life and the people inhabiting it.

Who has not heard his living word

Who in life has not met his own?

Immortal creations of Krylov

We love each year more and more.

With a school desk, we got along with them,

In those days, the primer was barely comprehended.

And forever remain in my memory

Winged krylov words. M.Isakovsky

In total, I.A. Krylov wrote more than 200 fables and published 9 books. He died, being recognized as the luminary of literature.

Monument to I.A. Krylov in the Summer Garden, St. Petersburg. Sculptor Klodt P.K.

The grave of I.A. Krylov at the Tikhvin cemetery in the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, St. Petersburg

I. A. Krylov

Aesop

A Crow and a fox

How many times have they told the world

That flattery is vile, harmful; but everything is not for the future,

And in the heart the flatterer will always find a corner.

Somewhere a god sent a piece of cheese to a crow;

Crow perched on the spruce,

I was quite ready to have breakfast,

Yes, I thought about it, but I kept the cheese in my mouth.

To that misfortune, the Fox fled close by;

Suddenly, the cheese spirit stopped Lisa:

The fox sees the cheese, -

Cheese captivated the fox,

The cheat approaches the tree on tiptoe;

He wags his tail, does not take his eyes off the Crow

And he says so sweetly, breathing a little:

"Darling, how pretty!

Well, what a neck, what eyes!

To tell, so, right, fairy tales!

What feathers! what a sock!

Sing, little one, don't be ashamed!

What if, sister,

With such beauty, you are a master of singing,

After all, you would be our king-bird!"

Veshunin's head was spinning with praise,

From joy in the goiter breath stole, -

And to Lisitsy's friendly words

The crow croaked at the top of its throat:

Cheese fell out - with him there was a cheat.

RAVEN AND FOX

Raven managed to get a piece of cheese, he flew up a tree, sat down there and caught the eye of the Fox. She decided to outwit Raven and says: "What a handsome fellow you are, Raven! And the color of your feathers is the most regal! If only you had a voice, you would be the master of all birds!" That's what the bastard said. Crow got hooked. He decided to prove that he had a voice, croaked at the top of his lungs and dropped the cheese. The Fox raised her prey and said: "You have a voice, Raven, but you never had a mind." Don't trust your enemies - it won't work.

I. A. Krylov

Aesop

FOX AND GRAPES

The hungry Fox noticed a bunch of grapes hanging from the vine and wanted to get it, but could not. She left and said: "He has not yet matured." Another cannot do anything due to lack of strength, but blames chance for this.

Fox and grapes

Hungry godmother Fox climbed into the garden;

In it, the grapes were reddened.

The gossip's eyes and teeth flared up;

And brushes juicy, like yachts, burn;

Only trouble is, they hang high:

Whence and how she comes to them,

Though the eye sees

Yes, the tooth is numb.

Breaking through the whole hour in vain,

She went and said with annoyance: “Well!

Looks like he's good

Yes, green - no ripe berries:

You'll get the hang of it right away."

Popular expressions from Krylov's fables

Have you been singing? This case: So come on, dance

And Vaska listens and eats

"Dragonfly and Ant"

"The Cat and the Cook"

Although the eye sees, but the tooth is numb

The strong always have the powerless to blame

"The Fox and the Grapes"

"Wolf and Lamb"

"Elephant and Pug"

Hey Moska! Know that she is strong when she barks at an elephant.

And you, friends, no matter how you sit down, you are not good at musicians

Both children and adults love to read and listen to fables. The texts of the fables are ancient. They appeared a very long time ago. In ancient Greece, for example, Aesop's fables were known in prose. The most prominent and sensational fables of modern times were the fables of Lafontaine. In Russian poetry, many authors-fabulists have shown themselves, but the fables of Krylov, Tolstoy and Mikhalkov have become the most famous.

What is a fable and how does it differ from a fairy tale or a poem? The main difference between a fable and other literary genres is the moralizing and more often even satirical nature of writing. Although the main characters of the fables are animals or even objects, the story is still about people, and their vices are ridiculed. And of course, an integral part of the fable is its moral. More often pronounced, written at the end of the fable, and sometimes veiled, but in any case understandable.

As for the origin of fables, there are only two concepts. The first of them is German, and the second is American. The German one says that fairy tales about animals were born from myths, from which, in turn, children's fables began to stand out separately, the basis of which was the text, and morality was already an addition unusual for a fairy tale. The American school believes that the moral of the fable is the basis, but the text of the fable for children is an addition that might not exist.

The fables that have survived to this day, with rare exceptions, represent animals as the main characters. For example, a fox or a wolf behave like people and talk like people. At the same time, one or more human vices are attributed to each animal, which are condemned. The usual cunning of a fox, the wisdom of an owl, the cunning of a snake and other virtues or vices. The characteristic features of people are often clearly traced.

Fables for children are also good because they are very small in size, they are read quickly, regardless of whether they are in verse or prose, and therefore they are perceived better. You will not have time to lose the thread, but perceive the meaning on the fly, often even children immediately understand the morality and all the conclusions. You can read more than one children's fable at a time, but several at once, but you shouldn't be zealous either - the child's interest will be lost and the meaning of reading will disappear.

Sometimes there are unique fables for children, which are always well-known, and whose heroes are so characteristic characters that their names are often used as common nouns. In this section, we collect the fables of the best authors, those who really brought something new to this genre and are recognized fabulists of world literature.

The emergence of the fable as a genre dates back to the 5th century BC, and the slave Aesop (VI-V centuries BC) is considered its creator, who was unable to express his thoughts in a different way. This allegorical form of expressing one's thoughts was subsequently called the "Aesopian language". Only around the 2nd century BC. e. fables began to be written down, including Aesop's fables. In ancient times, the famous fabulist was the ancient Roman poet Horace (65–8 BC).

In the literature of the 17th-18th centuries, ancient subjects were processed.

In the 17th century, the French writer La Fontaine (1621–1695) revived the fable genre again. Many of the fables of Jean de La Fontaine are based on the plot of Aesop's fables. But the French fabulist, using the plot of an ancient fable, creates a new fable. Unlike ancient authors, he reflects, describes, comprehends what is happening in the world, and does not strictly instruct the reader. Lafontaine focuses more on the feelings of his characters than on moralizing and satire.

In 18th-century Germany, the poet Lessing (1729–1781) turned to the fable genre. Like Aesop, he writes fables in prose. For the French poet Lafontaine, the fable was a graceful short story, richly ornamented, "a poetic toy." It was, in the words of Lessing's fable, a hunting bow, so beautifully carved that it lost its original purpose, becoming the decoration of the living room. Lessing declares literary war on Lafontaine: "The narrative in the fable," he writes, "...should be compressed to the utmost; deprived of all ornaments and figures, she must be content with clarity alone" ("Abhandlungen uber die Fabel" - Discourses on the fable , 1759).

In Russian literature, the foundations of the national fable tradition were laid by A.P. Sumarokov (1717–1777). His poetic motto was the words: "As long as I do not fade with decrepitude or death, I will not stop writing against vices ...". The fables of I.A. Krylov (1769–1844), which absorbed the experience of two and a half millennia, became the pinnacle in the development of the genre. In addition, there are ironic, parodic fables of Kozma Prutkov (A.K. Tolstoy and the Zhemchuzhnikov brothers), revolutionary fables of Demyan Bedny. The Soviet poet Sergei Mikhalkov, whom young readers know as the author of "Uncle Styopa", revived the fable genre, found his own interesting style of modern fable.

One of the features of fables is allegory: a certain social phenomenon is shown through conditional images. So, behind the image of Leo, traits of despotism, cruelty, injustice are often guessed. The fox is a synonym for cunning, lies and deceit.

It should be noted such features of the fable:

a) morality;

b) allegorical (allegorical) meaning;

c) the typicality of the described situation;

d) characters-characters;

e) ridicule of human vices and shortcomings.

V.A. Zhukovsky in the article "On the fable and fables of Krylov" pointed out four main features of the fable.

First fable feature - character traits, then how one animal differs from another: “Animals represent a person in it, but a person is only in some respects, with some properties, and each animal, having with it its inalienable permanent character, is, so to speak, ready and clear for everyone an image of both a person and a character that belongs to him. You make a wolf act - I see a bloodthirsty predator; bring a fox onto the stage - I see a flatterer or a deceiver ... ". So, the Donkey personifies stupidity, the Pig - ignorance, the Elephant - sluggishness, the Dragonfly - frivolity. According to Zhukovsky, the task of a fable is to help the reader understand a difficult everyday situation using a simple example.

Second feature of the fable, writes Zhukovsky, is that "transferring the reader's imagination to new dreamy world, you give him the pleasure of comparing the fictional with the existing (which the first serves as a likeness), and the pleasure of comparison makes morality itself attractive. "That is, the reader may find himself in an unfamiliar situation and live it together with the characters.

Third feature of the fable moral lesson, morality condemning the character's negative quality. "There is a fable moral lesson which you give to man with the help of cattle and inanimate things; presenting to him as an example creatures that are different from him by nature and completely alien to him, you spare his vanity, you force him to judge impartially, and he insensitively pronounces a severe sentence on himself," writes Zhukovsky.

Fourth feature - instead of people in the fable, objects and animals act. "On the stage on which we are accustomed to seeing a person acting, you bring out with the power of poetry such creations that are essentially removed from it by nature, miraculousness, just as pleasant for us as in the epic poem the action of supernatural forces, spirits, sylphs, gnomes and the like. The strikingness of the miraculous is communicated in a certain way to the morality that is hidden under it by the poet; and the reader, in order to reach this morality, agrees to accept the miraculousness itself as natural.