Famous commanders of World War II 1941 1945. Commanders of the Great Patriotic War

Battle of Stalingrad. Our troops number more than a million. There are more than a million enemies. By April 16, 1945, two and a half million of our soldiers were operating in the Berlin direction. They were opposed by a group of more than a million fascists. And in addition, there is “inanimate force”: huge concentrations of tanks and artillery, giant flocks of aircraft.

And with such “density of fire” the battles lasted a long time. Counteroffensive at Stalingrad - 75 days. And “Mamaevo’s Massacre” took three hours. And the Battle of Poltava lasted almost as long.

But, when comparing, we will not argue that the great battles of past centuries are just “battles of local significance” if we measure them by the standards already known to us. The great future has never diminished the great past.

We are talking about something else - about commanders.

Napoleon said that many of the questions facing a commander were a mathematical problem worthy of the efforts of Newton and. He meant his time. But what can we say about our commanders? How to measure the complexity of the tasks facing them?

Zhukov, Vasilevsky, Rokossovsky, Konev, Vatutin, Tolbukhin, Chernyakhovsky, Meretskov, Bagramyan. The names speak for themselves. They say a lot to many people. Moreover, the series can be continued further; even its length is amazing.

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov

General G.K. Zhukov, a platoon and squadron commander in the civil war, the hero of Khalkhin Gol, became the chief of the General Staff back in January 1941, at the age of forty-four. He held the position until July 30, that is, a little more than six months. The Great Patriotic War, as we see, accounts for a month and a little more than a week of this period. Then, in civilian terms, he was transferred to another job. This happened in the bitter days of our failures.

Very little time will pass, and Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov will become Deputy Supreme Commander-in-Chief. But it will be so. Very soon and very soon. The hours and years count on the clock of war.

The first thing Zhukov will do in his new capacity as commander of the Reserve Front will be Yelnya, where he will go to organize a counterattack.

He will understand a lot very quickly, that our units are firing artillery not at actual enemy firing points, but at supposed ones.

He will understand that, while delaying decisive action, he must constantly keep the enemy in suspense, exhaust him, and even mislead him with his activity.

Let us remember: Zhukov replaced the former commander of the Leningrad Front when Army Group North, having captured Shlisselburg, surrounded Leningrad. The enemy tried with all his might to turn the blockade ring into a suffocating noose thrown around the neck of the tormented city.

Zhukov stayed in Leningrad for less than a month and was urgently recalled - now Moscow was in mortal danger. Fulfilling his longed-for dream - to capture the Soviet capital in order to thereby surpass Napoleon (at that time Moscow was not the first city of Russia), Hitler sent almost half of all the troops that operated on the Soviet-German front to the operation, including two-thirds of all tank and motorized divisions. He remembered the experiences of Paris, Oslo, Copenhagen, Belgrade.

The same person goes precisely to the “boiling points”. According to Vasilevsky, Zhukov was the most noticeable in the main cohort of Soviet commanders, and turns out to be where he should be every time. And this despite his “hotness”, his independent character. But he will not change - he will remain the same. But the attitude towards such people will become different (“Gradually, under the pressure of the circumstances of the course of the war,” Vasilevsky would later write). To those who know their business perfectly, for whom the interests of the cause, the interests of Victory are above all.

Rokossovsky Konstantin Konstantinovich

We often hear and repeat these words: time dictates, time demands. That's when - during the war - it became absolutely clear that these were not just words. That's when it became absolutely obvious that the principles of personnel selection are vitally important. Wartime complicated many things, but it also unexpectedly simplified many things - for example, the view of who was considered a promising person worthy of nomination.

Rokossovsky started the war not as a 44-year-old general, but as a very young man. In civilian life he made a daring raid on the White headquarters train, took part in the defeat and capture of Baron Ungern, and was awarded the Order of the Red Banner.

In fact, in nine months, minus the time spent in the hospital after being wounded, Konstantin Konstantinovich Rokossovsky went from corps commander to front commander. Rapid growth, instant assessment of merit. Instant, but not hasty.

If you think about it, Rokossovsky’s “official” growth was facilitated by his enemies - they gave him commendable characteristics. How? At least this: in January 42, the Sixteenth Army was transferred to the Sukhinichi area, and an incident occurred there that at first seemed inexplicable.

The Nazi units opposing our troops suddenly abandoned their positions and retreated seven to eight kilometers. Without a fight, without any coercion on our part.

It later became clear what prompted them to act this way - they heard a rumor about the arrival of the Sixteenth Army. The enemy already knew the name of its commander well, and therefore decided, without tempting fate, to withdraw the troops to more prepared positions.

During the war, responsibility for decisions made sharply increased. The need for these decisions to be error-free has become more acute than ever: the cost of every mistake, especially in decisions of a military nature, has never been higher.

By accepting them, they risked not their position, not their reputation, they not only put themselves at risk, but so many others, their lives - the lives of tens, hundreds, thousands.

Chernyakhovsky Ivan Danilovich

The war answered all questions incomparably quickly. A decision was made - and everything became clear tomorrow, or even today - an hour later.

When in one of the battles the artillery fell behind, changing firing positions - and every minute was valuable, otherwise the offensive would bog down, Ivan Danilovich Chernyakhovsky - and this was, it seems, for the first time in the history of the Great Patriotic War - was removed from firing positions and moved to the front line to fight by the ground enemy the main group of the army's anti-aircraft artillery.

The anti-aircraft guns did not hit planes, but tanks and fortified enemy positions. This was a big risk, but Chernyakhovsky, having made such a decision, hoped to break the enemy’s resistance in an hour or two. And he turned out to be right.

In another battle, again remembering Suvorov’s order: one minute decides the outcome of battles, one hour - the success of the campaign, one day - the fate of the country, not allowing the enemy to gain a foothold on advantageous lines, and therefore, avoiding unjustified losses, Chernyakhovsky orders the troops to force the Dnieper.

Without pulling up the pontoon-bridge parks, without ensuring the simultaneous crossing of infantry, tanks and artillery, cross on rafts and fishing boats. The plan was for surprise. And to German loyalty to the letter of the charter.

The general knew that in all the instructions of the German army, crossing such large rivers was allowed only if engineering crossing facilities were available. He knew that the Germans would not dare to allow, even if this was happening before their eyes, that someone was doing something they themselves would never do. And again I was right.

And when, under fierce enemy fire, our advanced units reached the opposite bank and entered into an unequal battle, Chernyakhovsky conveyed to the advanced units: “I am sending reinforcements, I will support you with fire. Order: expand the bridgehead. I’ll go to you myself!”

The bridgehead was not only maintained, but also expanded.

They were like-minded people, our outstanding military leaders. Everyone thought and fought outside the box, faithful to the rule that Chernyakhovsky formulated as follows: a commander in battle should not do what the enemy is looking for and expecting from him.

Everyone understood that the true commander of a war for those who expect to win it must be a thought - new, deep, unexpected.

At the age of 37, Ivan Danilovich Chernyakhovsky was already commanding the front. Now, knowing how he fought, it’s not easy to even imagine that someone could have thought at one time: isn’t it too early for him to take such a post? For him, commanding an army is an achievement beyond his age?

Nikolai Fedorovich Vatutin, who was the front commander at that time, suggested that Chernyakhovsky take command of the army. He was only five years older, but managed to test himself in battles with the Makhnovists, and by the beginning of the war, at thirty-nine years old, he already held the high post of First Deputy Chief of the General Staff.

The offer to take command of the army took Chernyakhovsky by surprise:

It's only been a month since I commanded the corps.

A month in war is a very long time.

There are other generals, more experienced, deserved, my appointment will hurt their pride.

Well, here’s the thing,” Vatutin said almost sternly, “now is not the time to talk about someone’s pride.” The enemy put us in harsh conditions. And we cannot ignore this.

A man of position, with past merits, he seemed much older than the youngest of the front commanders. By the way, other major military leaders also had past achievements.

Konev Ivan Stepanovich and Tolbukhin Fedor Ivanovich

Konev stood at the head of the front at the age of 43, and first announced himself in the years of his combat youth - the red commissar of armored train No. 102 “Grozny”, division commissar, participant in the suppression of the counter-revolutionary rebellion in Kronstadt.

Tolbukhin, who in those years seemed to himself an elderly man, although he was only two years older than Zhukov and Rokossovsky, three years older than Konev, fought against Yudenich and the White Poles, was awarded the Order of the Red Banner for personal bravery, was awarded three times with a personalized silver watch with the inscription "To the honest warrior of the workers and peasants."

But even with regard to past merits, time has spoken quite clearly - a real war cannot be won by past victories, or even by the methods by which they were achieved. The path to victories in a modern war must be new, modern. Different times, different battles. And the commanders are different.

"Can not". Even if they wanted to. It is not man who dictates, it is time. Although someone, some person, much less impartial than time, could say: really, what’s the rush? Let the young general get used to his previous position. He will gain experience in leadership work... He still has everything ahead...

The military leader was required to constantly comprehend the situation, sometimes instantly solve complex problems, while minimizing possible mistakes. The work of a commander, ideally, is unmistakable creativity. But is it possible to create with the guarantee that you will avoid mistakes? Is one compatible with the other? But the fact of the matter is that someone managed to get closer to the ideal. It was then that time “interceded” for such people, demanding immediate recognition, immediate promotion. For the ability to fight, how to do one’s military work, such “trifles” as a complex character, like youth were forgiven... The most promising, in any case, turned out to be precisely those personnel changes that were made “in the spirit of the times,” not pre-war or post-war - military .

Govorov Leonid Alexandrovich

With the name of Leonid Aleksandrovich Govorov - he commanded the Leningrad Front - the heroic epic of the great city, the breakthrough of the Leningrad blockade, went down in history forever. Little talkative, dry, even somewhat gloomy in appearance, he could not or did not want to make an impression that was advantageous to himself.

However, this quality of nature is not the only thing that could prevent the future marshal from making a worthy contribution to the defeat of fascism and demonstrating his abilities as a strategist. In his early youth, due to difficult circumstances, he found himself in the Kolchak army, and although he quickly parted with it, and subsequently fought with, he was wounded twice in battles for Soviet power, awarded the Order of the Red Banner, who could guarantee that not a single personnel officer would ever be glance sideways at the “dark page” of his biography. But, as we already know, nothing stopped it. And Zhukov “looked after” him, seeing a major military talent in Govorov.

Vasilevsky Alexander Mikhailovich

Preparing a counteroffensive near Stalingrad, the Soviet Supreme High Command sent its representatives to the fronts. Chief of the General Staff Alexander Mikhailovich Vasilevsky arrived at the Stalingrad Front. The operation was scheduled to begin on October 20, 1942. But it started a month later. What happened? Who delayed the day that was so longed for? By what right and for what reasons?

Vasilevsky “dragged” with the start of the counteroffensive.

Arriving at the front, I became convinced that the day it began, judging by the state of the enemy, was chosen extremely well. The enemy could no longer attack, and did not have time to properly organize the defense. But such a “one-sided view” did not suit him. It was also necessary to take into account the fact that our fronts, in turn, had not yet had time to raise troops or concentrate material resources.

There are examples in the history of war when commanders with a “convenient character” hastened to console the Supreme High Command with optimistic assurances that in no way stemmed from a sober analysis of the situation. The arrogance of the leaders was paid for with the blood of the soldiers.

Facts of this kind explain not only what kind of Chief of the General Staff A.M. Vasilevsky was, but also why he became one, for what merits, and why he grew up.

Results of the leadership of the generals

As we see, having an inconvenient character is the “privilege” of not only Zhukov, but also other commanders. They knew how to firmly stand their ground. Yes, not on “ours” - on the common one, needed by the people, the country. Having been promoted to high positions by deeds, they proved by deeds that they occupied them by right.

Still, this ancient and solemn word “commander” sounds strange when talking about our contemporaries, including those who quite recently came to meetings with us, so to speak, according to Moscow time, and not thanks to a fabulous time machine, came not from legends, but from his apartments.

Did he himself, Ivan Chernyakhovsky, a thirteen-year-old orphan shepherd boy, who disappeared in the meadows with his flock from morning to evening, ever think that someday this “commander” would also refer to him? And Konstantin Rokossovsky is also an orphan from the age of fourteen? And the cook’s son Rodion Malinovsky? And Nikolai Voronov, our first marshal of artillery, when he was left without a mother as a child - did she commit suicide, tormented by hopeless poverty? And Georgy Zhukov, whose brother died of hunger, living in his Strelkovka in a house with a roof that had collapsed from disrepair? The same Zhukov, who would grow into the most prominent commander of his time, on behalf of the army and the people, will accept the surrender of Nazi Germany in Karlshorst, and then, riding a white horse, will host the Victory Parade on Red Square?

I believed that while in power, a person has no idea how damn difficult the situation of ordinary ordinary people can be. Whether this is true or not depends, probably, on many things.

Let us remember and compare: born in 1887, the one whose armies attacked Leningrad and then unsuccessfully tried to relieve the Nazi troops encircled at Stalingrad, was no longer a first-generation general, he represented the dynasty of the Prussian military aristocracy. And how many of them were there besides him in the avalanche that was rolling towards us - hereditary generals who were allegedly haunted by the “genes” of aggression and hatred that had settled in them from past centuries. Generals are from some families, soldiers are from others. It's like from another world.

This is a symbol. They were one family, our commanders and our soldiers.

Commanders of the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945

The creator of victory in the Great Patriotic War was the Soviet people. But to implement his efforts, to protect the Fatherland on the battlefields, a high level of military art of the Armed Forces was required, which was supported by the military leadership talent of the military leaders.

Distinctive professional qualities of the commanders of the Great Victory

The biographies of generals and military leaders are vividly inscribed in the chronicles of many peoples of the world. Domestic history has preserved the names of such outstanding commanders and naval commanders as Alexander Nevsky, Dmitry Donskoy, Peter I, Alexander Suvorov, Mikhail Kutuzov, Fyodor Ushakov, Pavel Nakhimov and others.

A commander is a military figure or military leader who directly leads the armed forces of a state or strategic, operational-strategic formations (fronts) during a war and has achieved high results in the art of preparing and conducting military operations.

In military literature, there are different opinions about the personal qualities of a commander. They all agree that he must have talent. It would be appropriate to refer to the opinion of the famous German military theorist Schlieffen, who in his work “Commander” wrote that “the presence of one or another high-ranking person in command of the troops, even on a state scale, does not make him a commander, because one cannot be appointed as a commander, for this one must have appropriate natural talent, talent, knowledge, experience, personal qualities.”

The Military Encyclopedia (2002) states that commanders include persons with military talent, creative thinking, the ability to foresee the development of military events, strong will and determination, combat experience, authority, and high organizational skills. These qualities allow a military leader to timely and correctly assess the current situation and make the most appropriate decisions.

A.M. Vasilevsky wrote about the personal qualities of commanders: “I believe that the point of view of our historical literature, according to which the concept of “commander” is associated with military leaders at the operational-strategic level, is correct. It is also true that the categories of commanders should include those military leaders who most clearly demonstrated their military art and talent, courage and will to win on the battlefields... The decisive measure of successful military leadership during the war years, of course, is the art of fulfilling the tasks of the front and army operations, inflict serious defeats on the enemy.”

The fact of recognition of the high leadership qualities of military leaders is their special awards of the Motherland and the highest military honors. Thus, for outstanding success in organizing and carrying out armed struggle on the fronts of the Great Patriotic War, the highest military commander’s order “Victory” was awarded to I.V. Stalin (twice), G.K. Zhukov (twice), A.M. Vasilevsky (twice), K.K. Rokossovsky, I.S. Konev, A.I. Antonov, L.A. Govorov, R.Ya. Malinovsky, K.A. Meretskov, S.K. Timoshenko, F.I. Tolbukhin. Almost all of them became Marshals of the Soviet Union during the war (A.I. Antonov became an army general), and I.V. In 1945, Stalin was awarded the highest military rank of Generalissimo of the Soviet Union.

It should be noted that not all prominent military leaders during the Great Patriotic War coped with their responsibilities while holding the positions of front commanders.

The harsh school of war selected and assigned 11 of the most outstanding commanders to the positions of front commanders by the end of the war. Of those who began to command the front in 1941, G.K. ended the war in the same positions. Zhukov, I.S. Konev, K.A. Meretskov, A.I. Eremenko and R.Ya. Malinovsky.

As the experience of the war showed, commanding troops on an operational-strategic scale in wartime was beyond the capabilities of even major military leaders. It was only possible for those with rich combat experience, deep military knowledge, and high strong-willed and organizational qualities.

Operational-strategic thinking should also be included among the features of military leadership talent. It was most strongly manifested in such of our commanders as G.K. Zhukov, A.I. Antonov, A.M. Vasilevsky, 6.M. Shaposhnikov, K.K. Rokossovsky, I.S. Konev, I.D. Chernyakhovsky, F.I. Tolbukhin and others. Their thinking was distinguished by its scale, depth, perspective, flexibility, reality and clarity for the closest persons and troops, which allowed them to successfully lead subordinate headquarters and troops. Here there was a fusion of operational thinking, will and practical action.

In addition to I.V. Stalin, essentially, only G.K. Zhukov, A.M. Vasilevsky, B.M. Shaposhnikov and A.I. Antonov systematically and fully engaged in the management of the Armed Forces on a strategic scale.

During the Great Patriotic War I.V. Stalin was the Chairman of the State Defense Committee, the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the USSR, and headed the Supreme Command Headquarters. As the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, he was distinguished by such features as the ability to foresee the development of the strategic situation and cover, in conjunction, military-political, economic, social, ideological and defense issues; the ability to choose the most rational methods of strategic action;

combining the efforts of the front and rear; high demands and great organizational skills; rigor, firmness, rigidity of management and a huge will to win.

Many government and military leaders praised Stalin's activities during the war. G.K. Zhukov, for example, wrote: “It must be said that with the appointment of I.V. Stalin as Chairman of the State Defense Committee, Supreme Commander-in-Chief and People's Commissar of Defense... his firm hand was immediately felt.”

Since the beginning of the war, operational-strategic training and strategic thinking of I.V. Stalin, according to some prominent military leaders, were not entirely sufficient. But thanks to his strong will and hard work, and extensive experience in government leadership, he managed to eliminate this gap by the beginning of the second period of the war. A.M. Vasilevsky, who knew Stalin well, noted: “It is necessary to write the truth about Stalin as a military leader during the war. He was not a military man, but he had a brilliant mind. He knew how to penetrate deeply into the essence of the matter and suggest military solutions.”

Outstanding commanders worked alongside Stalin throughout the war. The most striking personality among them was G.K. Zhukov. As a member of the Supreme Command Headquarters and deputy Supreme Commander, commanding various fronts for about two years, he was the developer and leader of the most important operations.

The main features of Zhukov's leadership talent are creativity, innovation, and the ability to make decisions unexpected for the enemy.

He was also distinguished by his deep intelligence and insight. According to the Italian military theorist Machiavelli, “nothing makes a great commander like the ability to penetrate the enemy’s plans.” This ability of Zhukov played a particularly important role in the defense of Leningrad and Moscow, when, with extremely limited forces, only through good reconnaissance and foreseeing possible directions of enemy attacks, he was able to collect almost all available means and repel enemy attacks.

Zhukov was also distinguished by careful planning of each operation, its comprehensive preparation and firmness in carrying out the decisions made. The will and firmness of Georgy Konstantinovich made it possible to mobilize all available forces and means of troops and achieve their goals.

Another outstanding strategic military leader at the Supreme Command Headquarters was A.M. Vasilevsky. Being the Chief of the General Staff for 34 months during the war, A.M. Vasilevsky was in Moscow for only 12 months, at the General Staff, and for 22 months he was at the fronts.

For the coordinated work of the Supreme Command Headquarters and the successful conduct of the most important strategic operations, the fact that G.K. Zhukov and A.M. Vasilevsky had developed strategic thinking and a deep understanding of the situation. It was this circumstance that led to its equal assessment and the development of far-sighted and informed decisions on the counter-offensive operation at Stalingrad, to the transition to strategic defense on the Kursk Bulge and in a number of other cases.

An invaluable quality of Soviet commanders was their ability to take reasonable risks. This trait of military leadership was noted, for example, by K.K. Rokossovsky. One of the remarkable pages of the military leadership of K.K. Rokossovsky - Belarusian operation, in which he commanded the troops of the 1st Belorussian Front.

When developing a solution and planning this operation, Rokossovsky showed courage and independence of operational thinking, a creative approach to fulfilling the task assigned to the front, and firmness in defending the decision made.

According to the original plan of the General Staff operation, it was envisaged to deliver one powerful strike. When reporting to Headquarters on May 23, 1944, Rokossovsky proposed delivering two strikes of approximately equal strength in order to encircle and destroy the enemy’s Bobruisk group. Stalin did not agree with this. Rokossovsky was twice asked to go out, “think carefully” and again report his decision. The front commander insisted on his own. He was supported by Zhukov and Vasilevsky. The Belarusian offensive operation was successful; more than five German divisions were surrounded and destroyed in the Bobruisk area. Stalin was forced to say: “What a fellow!.. He insisted and achieved his goal...”. Even before the end of this operation, Rokossovsky was awarded the rank of marshal.

An important feature of military leadership is intuition, which makes it possible to achieve surprise in a strike. I.S. possessed this rare quality. Konev. Some foreign military historians call him the “genius of surprise.” His talent as a commander was most convincingly and clearly demonstrated in offensive operations, during which many brilliant victories were won. At the same time, he always tried not to get involved in protracted battles in big cities and forced the enemy to leave the city with roundabout maneuvers. This allowed him to reduce the losses of his troops and prevent great destruction and casualties among the civilian population.

If I.S. Konev showed his best leadership qualities in offensive operations, then A.I. Eremenko - in defensive. A.M. Vasilevsky noted that “A.I. Eremenko... showed himself to be a persistent and decisive military leader. He showed himself brighter and more fully as a commander, of course, during the period of defensive operations.” Although he invariably achieved success in offensive operations.

In the preparation and conduct of these operations, Eremenko’s military leadership is characterized by the ability to organize reconnaissance of the enemy’s defense system, the search for extraordinary methods of conducting artillery and aviation training, careful preparation of troops for an offensive, and the creative organization of breaking through the enemy’s defense in depth.

A characteristic feature of a real commander is the originality of his plans and actions, avoidance of the template, and military cunning, in which the great commander A.V. succeeded. Suvorov. During the Great Patriotic War, R.Ya. was distinguished by these qualities. Malinovsky. Throughout almost the entire war, a remarkable feature of his talent as a commander was that in the plan of each operation he included some unexpected method of action for the enemy, and was able to mislead the enemy with a whole system of well-thought-out measures.

There is a known case when, after marching and repelling the first enemy attack in the Gromoslavka area, the tank corps of the second echelon of the 2nd Guards Army were running out of fuel. Malinovsky made a decision that was unexpected not only for the Germans, but also for his commanders. He ordered the tanks of these corps to be withdrawn from beams and other shelters to a clearly visible area, showing the enemy that the army still had a lot of untapped tank power. Hitler's command hesitated and did not dare to continue the attacks without regrouping the troops. As a result, Malinovsky gained much-needed time to transport fuel and ammunition.

The characteristic features of the military leadership talent of K.A. Meretskov were an exceptionally thorough approach to the preparation and comprehensive support of operations, a skillful choice of directions for the main attack, taking into account terrain conditions and the enemy’s location, a skillful concentration of troops and logistics in these directions, a bold maneuver to reach the enemy’s flanks and rear. Meretskov boldly took risks, skillfully and timely transferred troops from one sector to another, more threatened direction, and created tactical superiority over the enemy.

An integral part of his military leadership was high organization, courage, will, and painstaking work to build the moral fortitude of the troops. As a commander, he was close to the personnel, knew the mood of the soldiers well, and considered personal influence on his subordinates an indispensable attribute of command and control.

Thus, during the Great Patriotic War, many remarkable leadership qualities were revealed among our military leaders, which made it possible to ensure the superiority of their military art over the military art of the Nazis.

The military art of Soviet military leaders

The most important source of the victory of the Soviet people in the Great Patriotic War was the indestructible power of the Armed Forces, which withstood the most difficult test in single combat with the Nazi army and surpassed it. In the first period of the war, Soviet troops were forced to retreat into the interior of the country under the influence of a numerically superior enemy, who also had an advantage in military equipment. Nevertheless, our troops defended the Motherland with the greatest dedication and thwarted the enemy’s strategic plans with their steadfastness and courage.

By the winter of 1941-1942, Hitler’s plan for a “blitzkrieg” war was buried. In the fall of 1942, a balance was established in forces and means, then the clear superiority of the Soviet Armed Forces was revealed. The strategic initiative completely passed into their hands, until the final defeat of Hitler's army.

Many combat operations carried out by Soviet troops are unparalleled in the history of military art, both in their skill and in their results. In scale and art, they surpassed the military campaigns of famous commanders of antiquity and all outstanding events from the history of wars that preceded the Great Patriotic War. The victories of Soviet soldiers over the Wehrmacht in the great battles of Moscow and Stalingrad, Kursk and Belgorod, on the Dnieper and Neman, near Budapest and Vienna, on the Vistula and Oder and in the final Berlin offensive operation will forever remain in the memory of mankind.

The most important argument for the superiority of the military art of Soviet commanders is the victory in the war, the surrender of Nazi Germany. The complete defeat of Hitler's military machine is the most convincing confirmation of this.

Our commanders and military leaders of the armies allied to us defeated the strongest Hitler army, which had previously conquered all of Western and a significant part of Eastern Europe. They overthrew the canons of the seemingly invincible German military school.

Our military leaders never belittled the level of military art and preparedness of the German army; they saw its strengths, especially after the rapid defeat of a number of Western European armies. These included: the ability to misinform the enemy and achieve surprise; forestalling the enemy in strategic deployment; massive use of the Air Force to gain air superiority; wide maneuvering of forces and means; clear interaction between ground forces and aviation; skillful use of the resulting gap in the operational and combat formation of enemy troops, etc.

And, nevertheless, on the Soviet-German front, fighting from the very beginning of Hitler’s aggression began to develop not according to the Wehrmacht scenario.

The myth of the invincibility of the Nazi army was crushed already in 1941 near Moscow, for which over 30 field marshals, generals and senior Wehrmacht officers were removed from office.

G.K. Zhukov noted on this occasion: “When talking about how the Germans lost the war, we now often repeat that it’s not about Hitler’s mistakes, it’s about the mistakes of the German General Staff. But it must be added that Hitler, with his mistakes, helped the German General Staff to make mistakes, that he often prevented the General Staff from making more thoughtful, more correct decisions. And when in 1941, after the defeat of the Germans near Moscow, he removed Brauchitsch, Bock, and a number of other commanders and himself led the German ground forces, he undoubtedly rendered us a serious service. After this, both the German general staff and the German army group commanders found themselves connected to a much greater extent than before.”

As a number of domestic and foreign historians note, many of the mistakes of Hitler’s generals were predetermined by the professional selection system for the highest positions of the Wehrmacht that existed in those years. Thus, the American historian S. Mitchum, reviewing the biographies of German field marshals, emphasizes that by the time Hitler came to power, not a single field marshal had been in active service for more than 10 years. Over the next 10 years, Hitler awarded the rank of field marshal to 25 senior officers. 23 of them were awarded this title after the surrender of France in June 1940.

A number of the highest ranks of the Wehrmacht almost never went to the troops; all the day-to-day work of command and control was entrusted to headquarters officers, and therefore the state of affairs there was not always well understood. Of the 19 field marshals by the end of the war, only two remained in active service. “In general,” S. Mitchum concludes, “Hitler’s field marshals were a galaxy of surprisingly mediocre military leaders. And you can’t even call them geniuses of science to defeat them.”

This, in fact, was recognized by Hitler’s inner circle. So, on March 16, 1945, Goebbels made the following entry in his diary: “It turns out to be some kind of devilry: no matter how carefully we develop the latest operations, they are not carried out. The reason for this is that we cannot compete with the Russians in the selection of personnel at the top of the command.”

A significant argument in favor of the superiority of Soviet military art over German is the fact that our troops conducted strategic defense for only about 12 months, and offensive operations for 34 months. Of the 9 campaigns conducted during the war, 7 were carried out for offensive purposes. Our generals and military leaders carried out 51 strategic operations, 35 of them offensive. About 250 front-line and about 1000 army operations were carried out. All this suggests that the strategic initiative on the war fronts was mainly in the hands of Soviet military leaders, and they dictated the course of events.

In this regard, the response of Field Marshal Paulus is noteworthy when, at the Nuremberg trials, Goering’s lawyer tried to accuse him of allegedly teaching at a Soviet military school while in captivity. Paulus responded: “The Soviet military strategy turned out to be so superior to ours that the Russians could hardly need me, even if only to teach at the non-commissioned officer school. The best proof of this is the outcome of the battle on the Volga, as a result of which I was captured, and also the fact that all these gentlemen are sitting here in the dock.”

Some authors, when assessing the military art of the opposing sides during the war, incorrectly use and often deliberately distort data on losses. It is known that the total losses of the Soviet Union in the war amounted to 26.5 million people, of which about 18 million were civilians who died from bombings and fascist atrocities in the occupied territory.

The irretrievable losses of Nazi Germany amounted to 6.9 million people. In addition, similar losses of its allies who fought in Europe against the Soviet Union exceeded 1.7 million people. The excess of irretrievable losses of the Soviet Armed Forces over the corresponding German losses is due to fascist atrocities against Soviet prisoners of war. Of our 4.5 million prisoners of war and missing in action after the war, only 2 million people returned to the country, the rest died in captivity. At the same time, the vast majority of the 2 million German prisoners of war from the USSR returned to Germany.

These facts show the high morality of Soviet military leaders. At the Nuremberg trials, the cruelty of the majority of Wehrmacht military leaders was convincingly proven both towards the population of the occupied countries, prisoners of war, and towards their own soldiers and officers. For example, Keitel, Manstein and Scherner signed orders for mass executions. After the war, the Union of Returned Prisoners of War charged some of Hitler's generals with the mass executions of thousands of German soldiers.

Thus, the military leadership of the Soviet military leaders, who proved their superiority directly on the battlefields over the military art of Hitler’s generals, is the most important factor in victory and serves as an inspiring example for the Russian officer corps, for all soldiers.

In the introductory speech, one should note the relevance of the topic in connection with the 65th anniversary of Victory in the Great Patriotic War, emphasize the role of Soviet commanders and military leaders in achieving it, and show the importance of their military art for the modern Russian army.

When considering the first question, taking into account the interests of the listeners, it is advisable to use the example of several commanders of the Great Patriotic War to reveal the features of military leadership talent, to show their professional and human qualities that influenced the success of the battles.

In the course of revealing the second question, it is advisable to use specific examples and facts to demonstrate the superiority of the Soviet military leadership school over Hitler’s, and to point out the continuity of military leaders and commanders of the Russian army in the development of military theory and practice.

At the end of the lesson, it is necessary to draw brief conclusions, answer questions from students, and give recommendations on preparing for the seminar.

1. Gareev M. Victory commanders and their military legacy: Essays on the military art of commanders who completed the Great Patriotic War. - M., 2004.

2. Generals of Victory (55 years of Victory) // Landmark. - 2000. -№№ 1-12.

3. Samosvat O. Great Russian commanders, naval commanders and military leaders // Landmark. - 2009. -No. 8.

4. Shishov A. Outstanding Russian commanders // Landmark. - 2004. - No. 3.

Viktor Strelnikov, candidate of historical sciences, associate professor.

Lieutenant Colonel Dmitry Samosvat

The fate of millions of people depended on their decisions! This is not the entire list of our great commanders of the Second World War!

Zhukov Georgy Konstantinovich (1896-1974) Marshal of the Soviet Union Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov was born on November 1, 1896 in the Kaluga region, into a peasant family. During the First World War, he was drafted into the army and enrolled in a regiment stationed in the Kharkov province. In the spring of 1916, he was enrolled in a group sent to officer courses. After studying, Zhukov became a non-commissioned officer and joined a dragoon regiment, with which he participated in the battles of the Great War. Soon he received a concussion from a mine explosion and was sent to the hospital. He managed to prove himself, and for capturing a German officer he was awarded the Cross of St. George.

After the civil war, he completed the courses for Red commanders. He commanded a cavalry regiment, then a brigade. He was an assistant inspector of the Red Army cavalry.

In January 1941, shortly before the German invasion of the USSR, Zhukov was appointed chief of the General Staff and deputy people's commissar of defense.

Commanded the troops of the Reserve, Leningrad, Western, 1st Belorussian fronts, coordinated the actions of a number of fronts, made a great contribution to achieving victory in the battle of Moscow, in the Battles of Stalingrad, Kursk, in the Belarusian, Vistula-Oder and Berlin operations. Four times Hero of the Soviet Union , holder of two Orders of Victory, many other Soviet and foreign orders and medals.

Vasilevsky Alexander Mikhailovich (1895-1977) - Marshal of the Soviet Union.

Born on September 16 (September 30), 1895 in the village. Novaya Golchikha, Kineshma district, Ivanovo region, in the family of a priest, Russian. In February 1915, after graduating from the Kostroma Theological Seminary, he entered the Alekseevsky Military School (Moscow) and graduated from it in 4 months (in June 1915).

During the Great Patriotic War, as Chief of the General Staff (1942-1945), he took an active part in the development and implementation of almost all major operations on the Soviet-German front. From February 1945, he commanded the 3rd Belorussian Front and led the assault on Königsberg. In 1945, commander-in-chief of Soviet troops in the Far East in the war with Japan.

.

Rokossovsky Konstantin Konstantinovich (1896-1968) - Marshal of the Soviet Union, Marshal of Poland.

Born on December 21, 1896 in the small Russian town of Velikiye Luki (formerly Pskov province), in the family of a Pole railway driver, Xavier-Józef Rokossovsky and his Russian wife Antonina. After the birth of Konstantin, the Rokossovsky family moved to Warsaw. At less than 6 years old, Kostya was orphaned: his father was in a train accident and died in 1902 after a long illness. In 1911, his mother also died. With the outbreak of World War I, Rokossovsky asked to join one of the Russian regiments heading west through Warsaw.

With the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, he commanded the 9th Mechanized Corps. In the summer of 1941 he was appointed commander of the 4th Army. He managed to somewhat hold back the advance of the German armies on the western front. In the summer of 1942 he became commander of the Bryansk Front. The Germans managed to approach the Don and, from advantageous positions, create threats to capture Stalingrad and break through to the North Caucasus. With a blow from his army, he prevented the Germans from trying to break through to the north, towards the city of Yelets. Rokossovsky took part in the counter-offensive of Soviet troops near Stalingrad. His ability to conduct combat operations played a big role in the success of the operation. In 1943, he led the central front, which, under his command, began the defensive battle on the Kursk Bulge. A little later, he organized an offensive and liberated significant territories from the Germans. He also led the liberation of Belarus, implementing the Stavka plan - “Bagration”

Twice Hero of the Soviet Union

Konev Ivan Stepanovich (1897-1973) - Marshal of the Soviet Union.

Born in December 1897 in one of the villages of the Vologda province. His family was peasant. In 1916, the future commander was drafted into the tsarist army. He participates in the First World War as a non-commissioned officer.

At the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, Konev commanded the 19th Army, which took part in battles with the Germans and closed the capital from the enemy. For successful leadership of the army's actions, he receives the rank of colonel general.

During the Great Patriotic War, Ivan Stepanovich managed to be the commander of several fronts: Kalinin, Western, Northwestern, Steppe, Second Ukrainian and First Ukrainian. In January 1945, the First Ukrainian Front, together with the First Belorussian Front, launched the offensive Vistula-Oder operation. The troops managed to occupy several cities of strategic importance, and even liberate Krakow from the Germans. At the end of January, the Auschwitz camp was liberated from the Nazis. In April, two fronts launched an offensive in the Berlin direction. Soon Berlin was taken, and Konev took direct part in the assault on the city.

Twice Hero of the Soviet Union

Vatutin Nikolai Fedorovich (1901-1944) - army general.

Born on December 16, 1901 in the village of Chepukhino, Kursk province, into a large peasant family. He graduated from four classes of the zemstvo school, where he was considered the first student.

In the first days of the Great Patriotic War, Vatutin visited the most critical sectors of the front. The staff worker turned into a brilliant combat commander.

On February 21, Headquarters instructed Vatutin to prepare an attack on Dubno and further on Chernivtsi. On February 29, the general was heading to the headquarters of the 60th Army. On the way, his car was fired upon by a detachment of Ukrainian Bandera partisans. The wounded Vatutin died on the night of April 15 in a Kiev military hospital.

In 1965, Vatutin was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

Katukov Mikhail Efimovich (1900-1976) - Marshal of the armored forces. One of the founders of the Tank Guard.

Born on September 4 (17), 1900 in the village of Bolshoye Uvarovo, then Kolomna district, Moscow province, into a large peasant family (his father had seven children from two marriages). He graduated with a diploma of commendation from an elementary rural school, during which he was the first student in the class and schools.

In the Soviet Army - since 1919.

At the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, he took part in defensive operations in the area of the cities of Lutsk, Dubno, Korosten, showing himself to be a skillful, proactive organizer of a tank battle with superior enemy forces. These qualities were brilliantly demonstrated in the Battle of Moscow, when he commanded the 4th Tank Brigade. In the first half of October 1941, near Mtsensk, on a number of defensive lines, the brigade steadfastly held back the advance of enemy tanks and infantry and inflicted enormous damage on them. Having completed a 360-km march to the Istra orientation, the M.E. brigade. Katukova, as part of the 16th Army of the Western Front, heroically fought in the Volokolamsk direction and participated in the counter-offensive near Moscow. On November 11, 1941, for brave and skillful military actions, the brigade was the first in the tank forces to receive the rank of guards. In 1942, M.E. Katukov commanded the 1st Tank Corps, which repelled the onslaught of enemy troops in the Kursk-Voronezh direction, from September 1942 - the 3rd Mechanized Corps. In January 1943, he was appointed commander of the 1st Tank Army, which was part of the Voronezh, and later the 1st The Ukrainian Front distinguished itself in the Battle of Kursk and during the liberation of Ukraine. In April 1944, the armed forces were transformed into the 1st Guards Tank Army, which, under the command of M.E. Katukova participated in the Lviv-Sandomierz, Vistula-Oder, East Pomeranian and Berlin operations, crossed the Vistula and Oder rivers.

Rotmistrov Pavel Alekseevich (1901-1982) - chief marshal of the armored forces.

Born in the village of Skovorovo, now Selizharovsky district, Tver region, into a large peasant family (he had 8 brothers and sisters)... In 1916 he graduated from higher primary school

In the Soviet Army from April 1919 (he was enlisted in the Samara Workers' Regiment), a participant in the Civil War.

During the Great Patriotic War P.A. Rotmistrov fought on the Western, Northwestern, Kalinin, Stalingrad, Voronezh, Steppe, Southwestern, 2nd Ukrainian and 3rd Belorussian fronts. He commanded the 5th Guards Tank Army, which distinguished itself in the Battle of Kursk. In the summer of 1944, P.A. Rotmistrov and his army took part in the Belarusian offensive operation, the liberation of the cities of Borisov, Minsk, and Vilnius. Since August 1944, he was appointed deputy commander of the armored and mechanized forces of the Soviet Army.

Kravchenko Andrey Grigorievich (1899-1963) - Colonel General of tank forces.

Born on November 30, 1899 on the Sulimin farm, now the village of Sulimovka, Yagotinsky district, Kyiv region of Ukraine, in a peasant family. Ukrainian. Member of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) since 1925. Participant in the Civil War. He graduated from the Poltava Military Infantry School in 1923, the Military Academy named after M.V. Frunze in 1928.

From June 1940 to the end of February 1941 A.G. Kravchenko - chief of staff of the 16th tank division, and from March to September 1941 - chief of staff of the 18th mechanized corps.

On the fronts of the Great Patriotic War since September 1941. Commander of the 31st Tank Brigade (09/09/1941 - 01/10/1942). Since February 1942, deputy commander of the 61st Army for tank forces. Chief of Staff of the 1st Tank Corps (03/31/1942 - 07/30/1942). Commanded the 2nd (07/2/1942 - 09/13/1942) and 4th (from 02/7/43 - 5th Guards; from 09/18/1942 to 01/24/1944) tank corps.

In November 1942, the 4th Corps took part in the encirclement of the 6th German Army at Stalingrad, in July 1943 - in the tank battle near Prokhorovka, in October of the same year - in the Battle of the Dnieper.

Novikov Alexander Alexandrovich (1900-1976) - chief marshal of aviation.

Born on November 19, 1900 in the village of Kryukovo, Nerekhta district, Kostroma region. He received his education at the teachers' seminary in 1918.

In the Soviet Army since 1919

In aviation since 1933. Participant of the Great Patriotic War from the first day. He was the commander of the Northern Air Force, then the Leningrad Front. From April 1942 until the end of the war, he was the commander of the Red Army Air Force. In March 1946, he was illegally repressed (together with A.I. Shakhurin), rehabilitated in 1953.

Kuznetsov Nikolai Gerasimovich (1902-1974) - Admiral of the Fleet of the Soviet Union. People's Commissar of the Navy.

Born on July 11 (24), 1904 in the family of Gerasim Fedorovich Kuznetsov (1861-1915), a peasant in the village of Medvedki, Veliko-Ustyug district, Vologda province (now in the Kotlas district of the Arkhangelsk region).

In 1919, at the age of 15, he joined the Severodvinsk flotilla, giving himself two years to be accepted (the erroneous birth year of 1902 is still found in some reference books). In 1921-1922 he was a combatant in the Arkhangelsk naval crew.

During the Great Patriotic War, N. G. Kuznetsov was the chairman of the Main Military Council of the Navy and the commander-in-chief of the Navy. He promptly and energetically led the fleet, coordinating its actions with the operations of other armed forces. The admiral was a member of the Headquarters of the Supreme High Command and constantly traveled to ships and fronts. The fleet prevented an invasion of the Caucasus from the sea. In 1944, N. G. Kuznetsov was awarded the military rank of fleet admiral. On May 25, 1945, this rank was equated to the rank of Marshal of the Soviet Union and marshal-type shoulder straps were introduced.

Hero of the Soviet Union,Chernyakhovsky Ivan Danilovich (1906-1945) - army general.

Born in the city of Uman. His father was a railway worker, so it is not surprising that in 1915 his son followed in his father’s footsteps and entered a railway school. In 1919, a real tragedy occurred in the family: his parents died due to typhus, so the boy was forced to leave school and take up farming. He worked as a shepherd, driving cattle into the field in the morning, and sat down to his textbooks every free minute. Immediately after dinner, I ran to the teacher for clarification of the material.

During the Second World War, he was one of those young military leaders who, by their example, motivated the soldiers, gave them confidence and gave them faith in a bright future.

The names of some are still honored, the names of others are consigned to oblivion. But they are all united by their leadership talent.

USSR

Zhukov Georgy Konstantinovich (1896–1974)

Marshal of the Soviet Union.

Zhukov had the opportunity to take part in serious hostilities shortly before the start of World War II. In the summer of 1939, Soviet-Mongolian troops under his command defeated the Japanese group on the Khalkhin Gol River.

By the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, Zhukov headed the General Staff, but was soon sent to the active army. In 1941, he was assigned to the most critical sectors of the front. Restoring order in the retreating army with the most stringent measures, he managed to prevent the Germans from capturing Leningrad, and to stop the Nazis in the Mozhaisk direction on the outskirts of Moscow. And already at the end of 1941 - beginning of 1942, Zhukov led a counter-offensive near Moscow, pushing the Germans back from the capital.

In 1942-43, Zhukov did not command individual fronts, but coordinated their actions as a representative of the Supreme High Command at Stalingrad, on the Kursk Bulge, and during the breaking of the siege of Leningrad.

At the beginning of 1944, Zhukov took command of the 1st Ukrainian Front instead of the seriously wounded General Vatutin and led the Proskurov-Chernovtsy offensive operation he planned. As a result, Soviet troops liberated most of Right Bank Ukraine and reached the state border.

At the end of 1944, Zhukov led the 1st Belorussian Front and led an attack on Berlin. In May 1945, Zhukov accepted the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany, and then two Victory Parades, in Moscow and Berlin.

After the war, Zhukov found himself in a supporting role, commanding various military districts. After Khrushchev came to power, he became deputy minister and then headed the Ministry of Defense. But in 1957 he finally fell into disgrace and was removed from all posts.

Rokossovsky Konstantin Konstantinovich (1896–1968)

Marshal of the Soviet Union.

Shortly before the start of the war, in 1937, Rokossovsky was repressed, but in 1940, at the request of Marshal Timoshenko, he was released and reinstated in his former position as corps commander. In the first days of the Great Patriotic War, units under the command of Rokossovsky were one of the few that were able to provide worthy resistance to the advancing German troops. In the battle of Moscow, Rokossovsky’s army defended one of the most difficult directions, Volokolamsk.

Returning to duty after being seriously wounded in 1942, Rokossovsky took command of the Don Front, which completed the defeat of the Germans at Stalingrad.

On the eve of the Battle of Kursk, Rokossovsky, contrary to the position of most military leaders, managed to convince Stalin that it was better not to launch an offensive ourselves, but to provoke the enemy into active action. Having precisely determined the direction of the main attack of the Germans, Rokossovsky, just before their offensive, undertook a massive artillery barrage that bled the enemy’s strike forces dry.

His most famous achievement as a commander, included in the annals of military art, was the operation to liberate Belarus, codenamed “Bagration,” which virtually destroyed the German Army Group Center.

Shortly before the decisive offensive on Berlin, command of the 1st Belorussian Front, to Rokossovsky's disappointment, was transferred to Zhukov. He was also entrusted with commanding the troops of the 2nd Belorussian Front in East Prussia.

Rokossovsky had outstanding personal qualities and, of all Soviet military leaders, was the most popular in the army. After the war, Rokossovsky, a Pole by birth, headed the Polish Ministry of Defense for a long time, and then served as Deputy Minister of Defense of the USSR and Chief Military Inspector. The day before his death, he finished writing his memoirs, entitled A Soldier's Duty.

Konev Ivan Stepanovich (1897–1973)

Marshal of the Soviet Union.

In the fall of 1941, Konev was appointed commander of the Western Front. In this position he suffered one of the biggest failures of the beginning of the war. Konev failed to obtain permission to withdraw troops in time, and, as a result, about 600,000 Soviet soldiers and officers were surrounded near Bryansk and Yelnya. Zhukov saved the commander from the tribunal.

In 1943, troops of the Steppe (later 2nd Ukrainian) Front under the command of Konev liberated Belgorod, Kharkov, Poltava, Kremenchug and crossed the Dnieper. But most of all, Konev was glorified by the Korsun-Shevchen operation, as a result of which a large group of German troops was surrounded.

In 1944, already as commander of the 1st Ukrainian Front, Konev led the Lvov-Sandomierz operation in western Ukraine and southeastern Poland, which opened the way for a further offensive against Germany. The troops under the command of Konev distinguished themselves in the Vistula-Oder operation and in the battle for Berlin. During the latter, rivalry between Konev and Zhukov emerged - each wanted to occupy the German capital first. Tensions between the marshals remained until the end of their lives. In May 1945, Konev led the liquidation of the last major center of fascist resistance in Prague.

After the war, Konev was the commander-in-chief of the ground forces and the first commander of the combined forces of the Warsaw Pact countries, and commanded troops in Hungary during the events of 1956.

Vasilevsky Alexander Mikhailovich (1895–1977)

Marshal of the Soviet Union, Chief of the General Staff.

As Chief of the General Staff, which he held since 1942, Vasilevsky coordinated the actions of the Red Army fronts and participated in the development of all major operations of the Great Patriotic War. In particular, he played a key role in planning the operation to encircle German troops at Stalingrad.

At the end of the war, after the death of General Chernyakhovsky, Vasilevsky asked to be relieved of his post as Chief of the General Staff, took the place of the deceased and led the assault on Koenigsberg. In the summer of 1945, Vasilevsky was transferred to the Far East and commanded the defeat of the Kwatuna Army of Japan.

After the war, Vasilevsky headed the General Staff and then was the Minister of Defense of the USSR, but after Stalin’s death he went into the shadows and held lower positions.

Tolbukhin Fedor Ivanovich (1894–1949)

Marshal of the Soviet Union.

Before the start of the Great Patriotic War, Tolbukhin served as chief of staff of the Transcaucasian District, and with its beginning - of the Transcaucasian Front. Under his leadership, a surprise operation was developed to introduce Soviet troops into the northern part of Iran. Tolbukhin also developed the Kerch landing operation, which would result in the liberation of Crimea. However, after its successful start, our troops were unable to build on their success, suffered heavy losses, and Tolbukhin was removed from office.

Having distinguished himself as commander of the 57th Army in the Battle of Stalingrad, Tolbukhin was appointed commander of the Southern (later 4th Ukrainian) Front. Under his command, a significant part of Ukraine and the Crimean Peninsula were liberated. In 1944-45, when Tolbukhin already commanded the 3rd Ukrainian Front, he led troops during the liberation of Moldova, Romania, Yugoslavia, Hungary, and ended the war in Austria. The Iasi-Kishinev operation, planned by Tolbukhin and leading to the encirclement of a 200,000-strong group of German-Romanian troops, entered the annals of military art (sometimes it is called “Iasi-Kishinev Cannes”).

After the war, Tolbukhin commanded the Southern Group of Forces in Romania and Bulgaria, and then the Transcaucasian Military District.

Vatutin Nikolai Fedorovich (1901–1944)

Soviet army general.

In pre-war times, Vatutin served as Deputy Chief of the General Staff, and with the beginning of the Great Patriotic War he was sent to the North-Western Front. In the Novgorod area, under his leadership, several counterattacks were carried out, slowing down the advance of Manstein's tank corps.

In 1942, Vatutin, who then headed the Southwestern Front, commanded Operation Little Saturn, the purpose of which was to prevent German-Italian-Romanian troops from helping Paulus’ army encircled at Stalingrad.

In 1943, Vatutin headed the Voronezh (later 1st Ukrainian) Front. He played a very important role in the Battle of Kursk and the liberation of Kharkov and Belgorod. But Vatutin’s most famous military operation was the crossing of the Dnieper and the liberation of Kyiv and Zhitomir, and then Rivne. Together with Konev’s 2nd Ukrainian Front, Vatutin’s 1st Ukrainian Front also carried out the Korsun-Shevchenko operation.

At the end of February 1944, Vatutin’s car came under fire from Ukrainian nationalists, and a month and a half later the commander died from his wounds.

Great Britain

Montgomery Bernard Law (1887–1976)

British Field Marshal.

Before the outbreak of World War II, Montgomery was considered one of the bravest and most talented British military leaders, but his career advancement was hampered by his harsh, difficult character. Montgomery, himself distinguished by physical endurance, paid great attention to the daily hard training of the troops entrusted to him.

At the beginning of World War II, when the Germans defeated France, Montgomery's units covered the evacuation of Allied forces. In 1942, Montgomery became the commander of British troops in North Africa, and achieved a turning point in this part of the war, defeating the German-Italian group of troops in Egypt at the Battle of El Alamein. Its significance was summed up by Winston Churchill: “Before the Battle of Alamein we knew no victories. After it we didn’t know defeat.” For this battle, Montgomery received the title Viscount of Alamein. True, Montgomery’s opponent, German Field Marshal Rommel, said that, having such resources as the British military leader, he would have conquered the entire Middle East in a month.

After this, Montgomery was transferred to Europe, where he had to operate in close contact with the Americans. This was where his quarrelsome character took its toll: he came into conflict with the American commander Eisenhower, which had a bad effect on the interaction of troops and led to a number of relative military failures. Towards the end of the war, Montgomery successfully resisted the German counter-offensive in the Ardennes, and then carried out several military operations in Northern Europe.

After the war, Montgomery served as Chief of the British General Staff and subsequently as Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Europe.

Alexander Harold Rupert Leofric George (1891–1969)

British Field Marshal.

At the beginning of the Second World War, Alexander led the evacuation of British troops after the Germans captured France. Most of the personnel were taken out, but almost all the military equipment went to the enemy.

At the end of 1940, Alexander was assigned to Southeast Asia. He failed to defend Burma, but he managed to block the Japanese from entering India.

In 1943, Alexander was appointed Commander-in-Chief of Allied ground forces in North Africa. Under his leadership, a large German-Italian group in Tunisia was defeated, and this, by and large, ended the campaign in North Africa and opened the way to Italy. Alexander commanded the landing of Allied troops on Sicily, and then on the mainland. At the end of the war he served as Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean.

After the war, Alexander received the title of Count of Tunis, for some time he was Governor General of Canada, and then British Minister of Defense.

USA

Eisenhower Dwight David (1890–1969)

US Army General.

His childhood was spent in a family whose members were pacifists for religious reasons, but Eisenhower chose a military career.

Eisenhower met the beginning of World War II with the rather modest rank of colonel. But his abilities were noticed by the Chief of the American General Staff, George Marshall, and soon Eisenhower became head of the Operational Planning Department.

In 1942, Eisenhower led Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa. In early 1943, he was defeated by Rommel in the Battle of Kasserine Pass, but subsequently superior Anglo-American forces brought a turning point in the North African campaign.

In 1944, Eisenhower oversaw the Allied landings in Normandy and the subsequent offensive against Germany. At the end of the war, Eisenhower became the creator of the notorious camps for “disarming enemy forces”, which were not subject to the Geneva Convention on the Rights of Prisoners of War, which effectively became death camps for the German soldiers who ended up there.

After the war, Eisenhower was commander of NATO forces and then twice elected president of the United States.

MacArthur Douglas (1880–1964)

US Army General.

In his youth, MacArthur was not accepted into the West Point military academy for health reasons, but he achieved his goal and, upon graduating from the academy, was recognized as its best graduate in history. He received the rank of general back in the First World War.

In 1941-42, MacArthur led the defense of the Philippines against Japanese forces. The enemy managed to take American units by surprise and gain a great advantage at the very beginning of the campaign. After the loss of the Philippines, he uttered the now famous phrase: “I did what I could, but I will come back.”

After being appointed commander of forces in the southwest Pacific, MacArthur resisted Japanese plans to invade Australia and then led successful offensive operations in New Guinea and the Philippines.

On September 2, 1945, MacArthur, already in command of all U.S. forces in the Pacific, accepted the Japanese surrender aboard the battleship Missouri, ending World War II.

After World War II, MacArthur commanded occupation forces in Japan and later led American forces in the Korean War. The American landing at Inchon, which he developed, became a classic of military art. He called for the nuclear bombing of China and the invasion of that country, after which he was dismissed.

Nimitz Chester William (1885–1966)

US Navy Admiral.

Before World War II, Nimitz was involved in the design and combat training of the American submarine fleet and headed the Bureau of Navigation. At the beginning of the war, after the disaster at Pearl Harbor, Nimitz was appointed commander of the US Pacific Fleet. His task was to confront the Japanese in close contact with General MacArthur.

In 1942, the American fleet under the command of Nimitz managed to inflict the first serious defeat on the Japanese at Midway Atoll. And then, in 1943, to win the fight for the strategically important island of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands archipelago. In 1944-45, the fleet led by Nimitz played a decisive role in the liberation of other Pacific archipelagos, and at the end of the war carried out a landing in Japan. During the fighting, Nimitz used a tactic of sudden rapid movement from island to island, called the “frog jump”.

Nimitz's homecoming was celebrated as a national holiday and was called "Nimitz Day." After the war, he oversaw the demobilization of troops and then oversaw the creation of a nuclear submarine fleet. At the Nuremberg trials, he defended his German colleague, Admiral Dennitz, saying that he himself used the same methods of submarine warfare, thanks to which Dennitz avoided a death sentence.

Germany

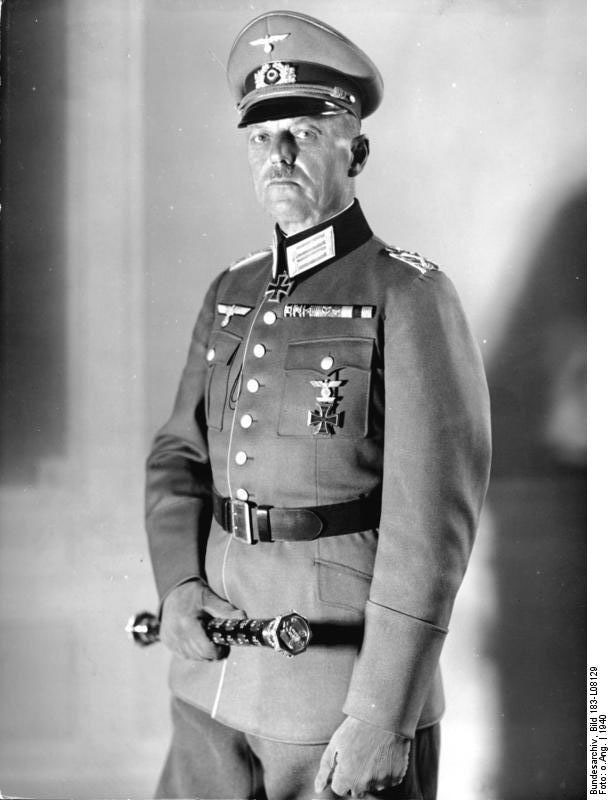

Von Bock Theodor (1880–1945)

German Field Marshal General.

Even before the outbreak of World War II, von Bock led the troops that carried out the Anschluss of Austria and invaded the Sudetenland of Czechoslovakia. At the outbreak of war, he commanded Army Group North during the war with Poland. In 1940, von Bock led the conquest of Belgium and the Netherlands and the defeat of French troops at Dunkirk. It was he who hosted the parade of German troops in occupied Paris.

Von Bock objected to an attack on the USSR, but when the decision was made, he led Army Group Center, which carried out an attack on the main direction. After the failure of the attack on Moscow, he was considered one of the main people responsible for this failure of the German army. In 1942, he led Army Group South and for a long time successfully held back the advance of Soviet troops on Kharkov.

Von Bock had an extremely independent character, repeatedly clashed with Hitler and pointedly stayed away from politics. After in the summer of 1942, von Bock opposed the Fuhrer’s decision to divide Army Group South into two directions, the Caucasus and Stalingrad, during the planned offensive, he was removed from command and sent to reserve. A few days before the end of the war, von Bock was killed during an air raid.

Von Rundstedt Karl Rudolf Gerd (1875–1953)

German Field Marshal General.

By the beginning of the Second World War, von Rundstedt, who held important command positions back in the First World War, had already retired. But in 1939, Hitler returned him to the army. Von Rundstedt became the main planner of the attack on Poland, code-named Weiss, and commanded Army Group South during its implementation. He then led Army Group A, which played a key role in the capture of France, and also developed the unrealized Sea Lion attack plan on England.

Von Rundstedt objected to the Barbarossa plan, but after the decision was made to attack the USSR, he led Army Group South, which captured Kyiv and other major cities in the south of the country. After von Rundstedt, in order to avoid encirclement, violated the Fuhrer's order and withdrew troops from Rostov-on-Don, he was dismissed.

However, the following year he was again drafted into the army to become commander-in-chief of the German armed forces in the West. His main task was to counter a possible Allied landing. Having familiarized himself with the situation, von Rundstedt warned Hitler that a long-term defense with the existing forces would be impossible. At the decisive moment of the Normandy landings, June 6, 1944, Hitler canceled von Rundstedt's order to transfer troops, thereby wasting time and giving the enemy the opportunity to develop an offensive. Already at the end of the war, von Rundstedt successfully resisted the Allied landings in Holland.

After the war, von Rundstedt, thanks to the intercession of the British, managed to avoid the Nuremberg Tribunal, and participated in it only as a witness.

Von Manstein Erich (1887–1973)

German Field Marshal General.

Manstein was considered one of the strongest strategists of the Wehrmacht. In 1939, as Chief of Staff of Army Group A, he played a key role in developing the successful plan for the invasion of France.

In 1941, Manstein was part of Army Group North, which captured the Baltic states, and was preparing to attack Leningrad, but was soon transferred to the south. In 1941-42, the 11th Army under his command captured the Crimean Peninsula, and for the capture of Sevastopol, Manstein received the rank of Field Marshal.

Manstein then commanded Army Group Don and tried unsuccessfully to rescue Paulus's army from the Stalingrad pocket. Since 1943, he led Army Group South and inflicted a sensitive defeat on Soviet troops near Kharkov, and then tried to prevent the crossing of the Dnieper. When retreating, Manstein's troops used scorched earth tactics.

Having been defeated in the Battle of Korsun-Shevchen, Manstein retreated, violating Hitler's orders. Thus, he saved part of the army from encirclement, but after that he was forced to resign.

After the war, he was sentenced to 18 years by a British tribunal for war crimes, but was released in 1953, worked as a military adviser to the German government and wrote a memoir, “Lost Victories.”

Guderian Heinz Wilhelm (1888–1954)

German Colonel General, commander of armored forces.

Guderian is one of the main theorists and practitioners of “blitzkrieg” - lightning war. He assigned a key role in it to tank units, which were supposed to break through behind enemy lines and disable command posts and communications. Such tactics were considered effective, but risky, creating the danger of being cut off from the main forces.

In 1939-40, in the military campaigns against Poland and France, the blitzkrieg tactics fully justified themselves. Guderian was at the height of his glory: he received the rank of Colonel General and high awards. However, in 1941, in the war against the Soviet Union, this tactic failed. The reason for this was both the vast Russian spaces and the cold climate, in which equipment often refused to work, and the readiness of the Red Army units to resist this method of warfare. Guderian's tank troops suffered heavy losses near Moscow and were forced to retreat. After this, he was sent to the reserve, and subsequently served as inspector general of tank forces.

After the war, Guderian, who was not charged with war crimes, was quickly released and lived out his life writing his memoirs.

Rommel Erwin Johann Eugen (1891–1944)

German field marshal general, nicknamed "Desert Fox". He was distinguished by great independence and a penchant for risky attacking actions, even without the sanction of the command.

At the beginning of World War II, Rommel took part in the Polish and French campaigns, but his main successes were associated with military operations in North Africa. Rommel headed the Afrika Korps, which was initially assigned to help Italian troops who were defeated by the British. Instead of strengthening the defenses, as the order prescribed, Rommel went on the offensive with small forces and won important victories. He acted in a similar manner in the future. Like Manstein, Rommel assigned the main role to rapid breakthroughs and maneuvering of tank forces. And only towards the end of 1942, when the British and Americans in North Africa had a great advantage in manpower and equipment, Rommel’s troops began to suffer defeats. Subsequently, he fought in Italy and tried, together with von Rundstedt, with whom he had serious disagreements affecting the combat effectiveness of the troops, to stop the Allied landing in Normandy.

In the pre-war period, Yamamoto paid great attention to the construction of aircraft carriers and the creation of naval aviation, thanks to which the Japanese fleet became one of the strongest in the world. For a long time, Yamamoto lived in the USA and had the opportunity to thoroughly study the army of the future enemy. On the eve of the start of the war, he warned the country's leadership: “In the first six to twelve months of the war, I will demonstrate an unbroken chain of victories. But if the confrontation lasts two or three years, I have no confidence in the final victory.”

Yamamoto planned and personally led the Pearl Harbor operation. On December 7, 1941, Japanese planes taking off from aircraft carriers destroyed the American naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and caused enormous damage to the US fleet and air force. After this, Yamamoto won a number of victories in the central and southern parts of the Pacific Ocean. But on June 4, 1942, he suffered a serious defeat from the Allies at Midway Atoll. This happened largely due to the fact that the Americans managed to decipher the codes of the Japanese Navy and obtain all the information about the upcoming operation. After this, the war, as Yamamoto feared, became protracted.

Unlike many other Japanese generals, Yamashita did not commit suicide after the surrender of Japan, but surrendered. In 1946 he was executed on charges of war crimes. His case became a legal precedent, called the “Yamashita Rule”: according to it, the commander is responsible for not stopping the war crimes of his subordinates.

Other countries

Von Mannerheim Carl Gustav Emil (1867–1951)

Finnish marshal.

Before the revolution of 1917, when Finland was part of the Russian Empire, Mannerheim was an officer in the Russian army and rose to the rank of lieutenant general. On the eve of the Second World War, he, as chairman of the Finnish Defense Council, was engaged in strengthening the Finnish army. According to his plan, in particular, powerful defensive fortifications were erected on the Karelian Isthmus, which went down in history as the “Mannerheim Line”.

When the Soviet-Finnish war began at the end of 1939, 72-year-old Mannerheim led the country's army. Under his command, Finnish troops for a long time held back the advance of Soviet units significantly superior in number. As a result, Finland retained its independence, although the peace conditions were very difficult for it.

During the Second World War, when Finland was an ally of Hitler's Germany, Mannerheim showed the art of political maneuver, avoiding active hostilities with all his might. And in 1944, Finland broke the pact with Germany, and at the end of the war it was already fighting against the Germans, coordinating actions with the Red Army.

At the end of the war, Mannerheim was elected president of Finland, but already in 1946 he left this post for health reasons.

Tito Josip Broz (1892–1980)

Marshal of Yugoslavia.