Corner of the magazine "Warrior of Russia". Memoirs of Admiral N.N. Amelko, minesweeping brigade of the Red Banner Baltic Fleet

(TSB, 3rd edition)

Memoirs of Admiral Amelko N.N. were posted on the site

http://www.amelko.ru/chast2.htm.

I found out about it by accident - through a slight altercation with the author of another “spam”, who also turned out to be the webmaster of the admiral’s site. The site included photographs and several parts of his memoirs. However, recently it has stopped opening, and I still have a very interesting “part 2” about the 40s and 50s in the Baltic (including the “Tallinn Crossing”), which is a pity to lose. Therefore, the idea arose to post it on this page. In general, the memoirs of Amelko N.N. were published in 2002. Information about this can be found on websites, for example:

We already knew quite accurately about the approach of war. On June 18, I was in Tallinn with the ship and cadets. In the evening, with the school teacher who led the practice, Captain II rank Khainatsky, we were at the Konvik restaurant on Torgovaya Street. Suddenly a cryptographer comes and whispers to me that a code has arrived from Moscow, encrypted with my commander’s code. He urgently went to the ship, took out the commander’s code from the safe and deciphered it: “Fleets are on combat readiness. All ships should immediately return to their bases at their permanent location.” He gave the command to urgently prepare the ship for departure. Mechanic Dmitriev reported that he was ready. Then the senior assistant commander of the ship, in turn, having received reports from the commanders of the combat units and the boatswain Veterkov, by the way, an excellent specialist in the long-term service, older than me in age, reported: “The ship is ready for battle and voyage.” We weighed anchor and moorings and went to Kronstadt. Appeared to Commander V.F. Tributsu. He says:

Your permanent location is Leningrad, near the school.

I reported that I needed to load coal.

This smells like war, you can go home and take care of family matters.

After loading the coal - and this is a time-consuming procedure - all the personnel with baskets and shovels from the shore run along the gangplank to the ship, load coal into the hatches of the coal pits and clean the boilers. I went by boat to Oranienbaum, then by train to the village of Uritsky and then by tram to the house. It was at this time that my neighbor told me that the war had begun. At home I told my wife that this war would be worse than the Finnish one. We decided that Tatochka (that’s what I called my wife) would go to visit her relatives in Moscow.

I didn’t stay at home overnight, I returned to the ship and sent the ship’s clerk - a very efficient foreman - to Leningrad to get a ticket for my wife on the train to Moscow. Two days later I saw my wife off with a train ticket. We lived on the outskirts of the city behind the Kirov plant, very far from the Moscow station, but the clerk at the Evropeyskaya hotel got a Lincoln car. There is pandemonium at the station. We found out where the train that will be served for boarding is located and on what route. In the Lincoln we drove from Litovskaya Street through the service entrance directly onto the platform, and at that time the train was already reversing for boarding. People rushed to the carriages as they walked; the entrances to the carriages were already packed with people. Then the clerk and I lifted my Tatochka into our arms and pushed her through the window of the carriage onto the top bunk. We said goodbye, and I saw her only three and a half years later. Sad I went to the ship.

Tallinn crossing. At the end of September 1939, the city of Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, became the main base and location of the main basing forces for the ships of the Baltic Fleet.I received an order to act in accordance with the mobilization plan, according to which I was supposed to join the brigade of skerry ships, the gathering place was the city of Tronzund, if you go to Vyborg from the sea. The channel at Tronzund is narrow, and I decided to stand at the pier with my bow towards the exit. He began to turn around, the bow of the ship rested against the pier, and the stern against the opposite shore. Using cables, a windlass and winches, the ship was turned around. I fiddled around for a long time and broke one winch. Then I found the headquarters of the brigade being formed and introduced myself to the commander - Captain 1st Rank Lazo. And he says:

It’s good that you turned around to leave, an order was received for the “Leningrad Council” to return to Kronstadt, and then go to Tallinn B by order of the Mine Defense Headquarters.

The morning of June 22, 1941 arrived. The training ship “Leningradsovet”, commanded by the author of these memoirs, was located in Kronstadt. Two 76-mm anti-aircraft guns were urgently installed on the ship at the bow and in the south (at the stern) and four DShK heavy machine guns on the turrets. Until mid-July, the ship made four trips from Kronstadt to Tallinn to replenish ammunition, food, and military equipment for its defenders. This was required because on August 5, 1941, troops of the 48th German Army cut through the 8th Army of the Northwestern Front and reached the coast of the Gulf of Finland, completely blocking Tallinn from land.

At the end of July, the ship “Leningradsovet”, being in Tallinn, stood at the pier of the Merchant Harbor and the headquarters of the Baltic Fleet Mine Defense was located on it. The commander of this formation was Vice Admiral Rall Yuri Fedorovich, the chief of staff was Captain 1st Rank A.I. Aleksandrov, deputy. the chief of staff - captain 2nd rank Polenov, all of them, as well as the flagship navigator Ladinsky, miner Kalmykov and other specialists of the Mine Defense headquarters were located and lived at the Leningradsovet.

The defense of Tallinn continued for three weeks: the 10th Rifle Corps of the 8th Army, subordinate to the Fleet Commander Admiral Tribune, a detachment of marines formed from the personnel of the ships (it also included 20 people from the crew of the Lenin-Gradsovet), a regiment of Latvian and Estonian workers, supported by naval artillery and naval aviation, stubbornly defended the capital of Estonia and the naval base. Fierce fighting on the outskirts of the city continued until August 27, but the forces were not equal. The enemy concentrated four infantry divisions, reinforced with tanks, artillery and aircraft, against the defenders of Tallinn. The ships began to be shelled with artillery and mortars. The ships left the berths for the inner roadstead, and then for the outer roadstead. On August 26, the chief of staff of the Mine Defense called me and said that an order had been received from the Supreme High Command headquarters to relocate the fleet to Kronstadt and Leningrad. He gave me a briefcase with money and a letter to his daughter and asked me (commander of the Leningradsovet, senior lieutenant Amelko N.N.) upon the ship’s arrival in Leningrad to give this briefcase to his daughter. He said that the headquarters was leaving the ship and would go on other ships, and he ordered me to go to the roadstead and receive instructions on when and how to leave. I asked

,what ship will he go on, Chief of Staff. He replied that he was on the destroyer Kalinin. I objected to him that he had a greater chance of reaching Kronstadt. And he answered, I remember verbatim: “No, you will get there, but I won’t,” a fatal premonition. All the headquarters officers left the ship, and I began to make my way to the exit from the Merchant Harbor to the roadstead, safely made my way through the shell explosions when leaving the harbor, maneuvering in the roadstead among other ships. Before my eyes, a shell hit the cruiser “Kirov” and a fire broke out near the gangway on the starboard side. I did not see any personnel on the upper deck of the cruiser and therefore gave a signal to the cruiser: “Commander, your ladder on the starboard side is burning.” Then I saw how they began to put out the fire.On August 27, a MO boat approached the Leningradsovet, Captain III rank Kovel came on board with a package and introduced himself as the navigator of the fourth convoy. Captain 1st Rank Bogdanov was appointed commander of the convoy. Kovel remained on the ship, and the MO boat moved away from the side with Bogdanov, I never saw him again. Having opened the package, I learned that “Leningrad Soviet will be the lead in the 4th convoy, four minesweepers converted into tugs are allocated for mine protection, that is, two pairs with Schultz trawls, the convoy will have 14 units of transport with troops and three submarines - little ones.” Departure at dawn on command.

At night, minesweepers and tugboats arrived, and transport also approached the outer roadstead. At dawn on August 28, I received a signal from the Kirov: “For the 4th convoy, form up and leave.” Navigator Kovel and navigator “Leningradsovet” laid out passage courses on the map, as indicated in the package. I gave the order to the minesweepers to line up and gave courses.

At this time, two “KM” boats approached the side of the ship - these are traveling boats of the fleet headquarters, I was familiar with their commanders before: they were in Leningrad in the Training detachment providing practice for cadets of the school named after M.V. Frunze. The commanders and midshipmen of the boats began to ask me: “Comrade commander, take us with you, we were abandoned, and we don’t know how or where to go.” I agreed, instructed my senior assistant Kalinin to put them on bakshtov (small boats, about 10 tons of displacement), gave them a hemp cable from the stern, and they stood “in tow.”

At Voindlo Island our fourth convoy lined up and began moving. We passed Keri Island, mines began to explode in the trawls, one of the minesweepers was blown up, political instructor Yakubovsky was thrown aboard the Leningradsovet by a blast wave from one of the minesweepers, landed on a tarpaulin awning and received almost no serious injuries. We only had one pair of minesweepers left, but the trawled strip was so small that those walking in the wake of the transport could not strictly adhere to it and began to be blown up by mines. Transport and ships were constantly attacked by Yu-87 and Yu-88 bombers. The two boats that I had on Bakshtov picked up floating people from ships and transports and landed them on the Leningradsovet. Somewhere abeam Yuminda we saw the burning and sinking transport “Veroniav”, on which mainly the employees of the fleet headquarters were evacuated. Our boats picked up and brought on board several dozen people - men and women. Near our side we saw a girl floating in only a shirt, holding on to a large suitcase. When we pulled her on board, it turned out to be an Estonian cashier from Tallinn customs, and the suitcase was stuffed with Estonian kroons. When asked what this money was for, she replied that she was responsible for it. The chief mate threw this suitcase overboard, threw his overcoat over her, then they changed her into working sailor uniform. The ship's battalion and supply staff changed the clothes of everyone whom the boats picked up and dropped off on board.

Soon we approached the Nargen-Porkolaud mine line. At this time, a squadron overtook us from the starboard side, four minesweepers “BTShch” passed, followed by the icebreaker “Suurtyl”, on which, as it turned out, the Estonian government, the head of which was Ivan Keben, was evacuated. Behind the icebreaker was the cruiser “Kirov” under the flag of fleet commander Vladimir Filippovich Tributs. They passed so close that the fleet commander shouted through a megaphone: “Amelko, how are you doing?” I didn’t know what to answer, and while I was thinking, they had already left, and it was useless to shout. Behind the Kirov was the leader of the destroyers, Yakov Sverdlov. At this time, from the Kirov, our signalmen read the semaphore: “There is a submarine periscope ahead on the bow of the Leningradsovet. “Yakov Sverdlov,” I’ll go out and bomb.” The latter gave off a “hat” of smoke. This means that he increased his speed, broke down and passed by “Leningradsovet” at 20-30 meters. On the bridge I saw the commander, Alexander Spiridonov. With him

I knew each other well before the war, we were in the same detachment and, while in Tallinn, we met several times. He was a bachelor, and we considered him a “dude.” We, young officers, did not wear the naval caps given to us, but ordered them in Tallinn on Narva-Mantu Street from Jacobson, a jacket and trousers from a workshop in Vyshgorod from an Estonian tailor. Somewhere in mid-August, Sasha Spiridonov came to my ship and offered to order overcoats made of castor fabric.I suggested that since he was talking about the overcoat, apparently we would soon be moving to Kronstadt, but would we get there? Spiridonov tells me:

Well, you know, drowning in a castor overcoat is more pleasant than in the one they give us.

So, passing by me, Spiridonov, standing on the bridge in a jacket, a white shirt with a tie, a Jacobson cap, a cutlass and a cigar in his mouth, shouted into a megaphone: “Kolya! Be healthy!". I answered him: “Okay, scratch it Sasha!” Having passed several cable lengths ahead of me, his ship exploded on a mine and sank. The legend that “Yakov Sverdlov” protected the cruiser “Kirov” from a torpedo fired by a submarine does not correspond to reality - it was blown up by a mine. The place of the Yakov Sverdlov in the wake was taken by two destroyers, and behind them the submarine S-5, which exploded before reaching us. The MO-4 boat picked up five people, including Hero of the Soviet Union Egipko, the boat dropped off four sailors to us, and Egipko remained on the boat, the rest of the personnel died - torpedoes detonated on the submarine. It's already starting to get dark. At this time, the cruiser was far ahead and fired with its main caliber at the enemy torpedo boats that had left the Finnish skerries. We didn't see any boats. We approached the place of death of “Yakov Sverdlov”, lights flashed on the water - these were signals given by sailors and officers, who were picked up by boats and brought on board. It should be clarified that the ship’s personnel were wearing vests that inflated when they fell into the water. The lights on the vests were powered by batteries. Each vest also had a whistle, and the one that fell into the water whistled, attracting attention. Second

a couple of minesweepers we were following also exploded on mines. By 10 p.m. visibility had decreased to 200 meters. In order not to be blown up by mines, we decided to anchor before dawn. Small ships and tugboats began to approach us, asking permission to tow the Leningradsovet, since the depth was great and their anchor chains did not allow us to anchor ourselves. At dawn we discovered about eight ships standing behind us on the bakshtov, one behind the other. We weighed anchor, pushed two floating mines away from the side with poles, and began moving towards the island of Gogland. Following the “Leningradsovet” in the wake were the military transport “Kazakhstan”, the floating plant “Sickle and Hammer” and two more transports. Continuous bombing of transports began, which were larger than the Leningrad Council. “Kazakhstan” caught fire, but the personnel, led by Captain Zagorulko, dealt with the fire and damage, and the transport reached Kronstadt on its own. “Hammer and Sickle” died. From the convoy there was only one “Leningrad Soviet” and three “baby” submarines, which submerged and followed us under the periscope. Then the Junkers attacked the Leningradsovet, flew in groups of 7-9 aircraft, circled above us and took turns diving onto the ship. The height of the explosions of our shells forced them to circle and drop bombs one by one. If you watch carefully, you can see when the bombs come off the plane, and by turning the ship to the right or left, increasing or decreasing the speed, you can avoid the bomb directly hitting the ship. That's what we did. For the quickest reaction, helmsman Bizin was transferred from the wheelhouse to the upper bridge; the drivers were ordered to quickly carry out signals to increase speed or stop the car. Thus, the ship withstood more than 100 bomber raids. Bombs were exploding nearby The fragments damaged the hull and wounded some people, including the commander, but a direct hit was avoided.We approached the southern tip of Gogland Island - there is a lighthouse and a signal and observation post. They asked by semaphore: “Which fairway did the squadron with the cruiser Kirov take?” We received no answer. The fact is that the tracing paper handed to us when leaving Tallinn showed the route along the northern fairway. But there was also a mine position on the Gogland reach. I decided to take the southern channel, a very narrow strait called Hailoda. Ships rarely sailed near Cape Kurgalsky and often ran aground. But I knew this passage well and already in the evening twilight I passed it safely and emerged into Luzheskaya Bay.

Night has come. After the last fierce attacks of the aircraft, the hydrocompasses failed, and there were two of them - “Geo-3” and the English Speri.” There were also the English “Hydraulic Steering” and “Courseograph” - echo sounder, but they were all out of order, leaving only one magnetic compass with dubious accuracy. In short, we lost our location. We saw glimpses of a navigation buoy. After a meeting with the navigators, it was suggested that this was the buoy of the Demonstein Bank. To make sure of this, the command boat was lowered and the ship's navigator Albert Kirsch was sent to the buoy. He approached it carefully and returned to the ship, confirming our assumption. Ahead on the right we saw a fire on the shore where the Peipia torpedo boat base was. Thus, we determined our place and went to the Shepelev lighthouse, where it was necessary to walk exactly along the fairway, since in this area the entire water space was blocked by anti-submarine nets on which explosive devices were suspended. When approaching this line, we periodically dropped depth charges, considering it possible that enemy submarines from the Finnish skerries might be in this area. But everything turned out well. We entered the fairway and entered the large Kronstadt roadstead. The cruiser “Kirov” was at anchor in the roadstead, they played the approach, everyone stood facing the side of the cruiser, on which the bugle also sounded and there, too, everyone stood “at attention” facing us. Requested

signal post where we are allowed to dock at the pier? And we received the answer: to go to the Ust-Rogatka pier. They dropped the anchor and moored with the stern not far from the battleship “Marat”, brought the gangplank ashore and all those raised from the water by the “Leningradsovet” from the dead ships were allowed to go ashore. And there were about 300 of them - officers, sailors, soldiers and civilians. So “Leningradsovet” completed the transition from Tallinn to Kronstadt. Several crew members were awarded orders and medals, and the commander, by order of the People's Commissar of the Navy, received his first award - the Order of the Red Banner, and was awarded the rank of lieutenant commander ahead of schedule.Leningrad blockade.

On September 22, the Germans carried out an air raid on ships stationed in Kronstadt. One of the bombs hit the bow of the battleship “Marat”, the artillery magazines of the bow tower detonated, the bow with the 1st tower was torn off, the ships standing near it were torn off their moorings, including the Leningrad City Council.”

Upon returning to Kronstadt from Tallinn, the command of the Baltic Fleet gave instructions from among the crews of the ships to form marine brigades to be sent to help the troops of the Leningrad Front in the defense of Leningrad. A total of eight brigades were formed. On my ship, we took one combat shift to defend the city back in Tallinn. None of them returned to the ship, and the second combat shift was taken off in Kronstadt. On the Leningradsovet and other ships there was only one combat shift left out of the three required by the state, mainly artillerymen, miners and signalmen. We slept in turns, right at the combat posts.

On September 24, the commander of the light forces detachment of the Red Banner Baltic Fleet, Vice Admiral Valentin Petrovich Drozd, called me to the cruiser “Kirov” and showed me a directive from the fleet commander V.F. Tributs, which ordered the ship to be mined in case of destruction. We discussed how to do this and decided: to put two depth charges in the artillery magazines and engine room, and keep the fuses in a personal safe in the ship’s commander’s cabin. Then Drozd unfolded the map and showed the place at the entrance to a large roadstead, where, at the signal “Aphorism,” the ship was to be blown up, next to the blown up battleship “October Revolution”. Dictation by V.P. Drozd described all these actions on a piece of paper, Drozd endorsed them, sealed them in an envelope, on which he wrote

“Open it personally to the commander upon receipt of the “Aphorism” signal and act according to the instructions. Keep in a personal safe."Returning to my ship, I ordered the ship to be mined. I soon learned that similar actions were carried out by the commanders of all ships. This “work” was strictly monitored by the heads of the special departments of the NKVD and reported to Army General G.K., who took command of the Leningrad Front. Zhukov. The ships fought in this condition until the blockade of Leningrad was lifted.

G.K. Zhukov commanded the Leningrad Front for 27 days. Some WWII researchers said and still say that Zhukov “saved” Leningrad. The blockade of the city lasted 900 days. It is absurd to claim that during the 27 days of his command of the Leningrad Front he saved Leningrad from the siege, especially at the beginning of the war. If we talk about personalities, L.A. did it. Govorov.

I knew G.K. well. Zhukova. As commander of the Pacific Fleet, he personally reported to him. I recognize him as the organizer of stopping the retreat of our troops on the Volga, despite Zhukov’s brutal methods of action in doing so. And, of course, I do not recognize him as a “brilliant” commander who “saved” Russia. It is known that all military operations were planned by Marshal Vasilevsky, and not Zhukov. Russia was saved by the people, our armed forces, with their courage, not sparing their lives.

At the end of September, “Leningradsovet” was included in the detachment of ships of the Neva River. The ship was transferred to Leningrad and placed on the right bank of the Neva at the Lesopark pier, with the task of supporting with fire the 2nd division of the people's militia (2nd DNO), which defended besieged Leningrad on the left bank

Neva opposite the village of Korchmino, right behind the Bolshevik plant.In addition to the Leningradsovet, the detachment of ships of the Neva River included one destroyer of the 7-u type, gunboats Oka, Zeya and others, the names of which I do not remember. Our task is, at the request of the commander of the people's militia division, to suppress German firing points with artillery fire or to support with fire the 2nd DNO, which has repeatedly tried to storm the village of Korchmino and advance in the direction of Shlisselburg. We had few shells, and when requests were received, the detachment commander allowed us to fire only 5-6 shells.

One day the commander of the 2nd DNO called me to his command post. I crossed the Neva on a boat and approached the division commander’s dugout. The sentry stopped me, questioned me and went into the dugout. I stand at the entrance and hear a soldier report: “Comrade division commander, the commander of the steamship has come to you, which is standing on the other side, almost opposite us, I didn’t remember his last name, and I didn’t understand the rank, either captain or lieutenant.” That's right - I was a lieutenant commander. The division commander asked if I could send a boat along the Neva at night and scout out what forces were defending the village of Korchmino. I agreed, lowered the boat, appointed senior lieutenant Kolya Goloveshkin as the navigator of the ship, sent with him boatswain Veterkov, radio operator Senya Durov and another sailor, armed them with machine guns, carbines, pistols, dressed them in camouflage suits and sent them up the river to the village of Korchmino. By dawn, our scouts reported that they had approached the pier and crawled into the village, where they found no one. They found one old woman who confirmed that, indeed, there was no one in the village except her, and that two days ago there were Germans in the village. She also said that two days ago our people approached the village and started shooting, the Germans opened fire back, and then both our people and the Germans retreated, and the village was empty. This was reported to the division commander. He said that they retreated that night due to heavy German fire and that he would take the village next time. I don't know whether he took it or not. To our knowledge, no.

Our rations were very bad. The rear of the Lenmorbaza decided that the Leningradsovet had died during the transition from Tallinn and removed the ship from allowance. But then they sorted it out and resumed the allowance. For each person they were given 250 grams of bread, if it can be called bread, 100 grams of flour, which was usually fed to calves, and a teaspoon of condensed milk - this is per person per day. On the shore, not far from where the ship was moored, there was a neutral zone, there was a potato field. I took a chance and sent three efficient sailors. At night they crawled and dug up potatoes, the “operation” was successful, but they only managed to dig up half a bag. We fried it in drying oil and ate it with pleasure.

Next to the pier where we were standing there was the so-called “Saratov colony” - a village in which German colonists lived. The Germans carried out air raids, usually after dark, planes flew from the direction of Shlisselburg, and from the houses of these colonists they launched missiles and gave target designations at our targets and ships. During the day we went around the houses, trying to find out who gave the signals, but the residents refused, saying that they didn’t do it. Once the commander of the Leningrad Front, Leonid Aleksandrovich Govorov, arrived, and I told him about it. He ordered surveillance to be established and allowed a gun salvo to be fired at houses firing signal flares. Zhdanov was with him and approved this decision. The next night we loaded a 76-mm cannon, set up surveillance of the houses, and as soon as the rocket took off, we fired a salvo at this house and blew it to pieces. The houses were of the dacha type. In the morning we went to look - there was no one there anymore. They only found cow hooves - apparently the cow had been killed. A wonderful meat soup was prepared from these hooves along with the skin. Enough for the entire crew. The sailors smeared mustard on their 250 grams of bread, and then drank a lot of water and plumped up. To prevent scurvy, they prepared pine and spruce branches, infused them and drank them.

In Leningrad, on Vasilievsky Island on the 2nd line, lived his father, stepmother Anna Mikhailovna and sister Alexandra, who worked in a pharmacy. I decided to visit them. There was no transport, I went on foot, and it was very far, across the Volodarsky Bridge along the embankment to the old Nevsky Prospekt, across the Palace Bridge along Tuchkova Embankment, only 15 kilometers. But I got there. The city amazed me, at every step there were frozen corpses, snow-covered tram cars, trolleybuses and buses in the snowdrifts, Gostiny Dvor was on fire, Passage and the Eliseevsky store were also on fire. Rare people, or rather shadows, wander through the streets. On the 2nd line at the gate of each house there are several corpses. I went up to the apartment, entered the room - my father and stepmother were standing at the window and arguing which German plane had flown by: a Messerschmidt or a Fockewulf. They were very happy about my arrival. I brought them 400 grams of bread, one onion and a bottle of pine infusion. It was just a feast. Five families lived in a five-room apartment, eleven people in total, five died, three were in the hospital, three people remained. Mother says:

Kolya, in the room opposite - Nikolai Fedorovich, a neighbor, died, and my father and I couldn’t carry him to the gate

.Well, I went and dragged the corpse to the gate onto the street - military vehicles were driving there, picking up the corpses and taking them to the cemetery, where they were stacked in piles. The shelling of the city began, the mother says that we need to go to the first floor under the arch of the house. The father objects and does not want to go down - the shells fall far away. I agreed with him, although the house was shaking and the dishes were clanking.

I rested a little and began to say goodbye to my family - I wanted to get to the ship before dark. Around 20 o'clock he returned, as they say, “without legs” and slept for a day.

The New Year has arrived, 1942. They put up Christmas trees in the cabins and modestly celebrated the New Year. We drank the small bottles of vodka that were given to us; I think they were called osmushki. I didn’t drink vodka, because somehow, long before that, the ship’s supply manager brought liquid onto the ship - this is fuel for Packard engines from torpedo boats supplied to us by the Americans. This liquid was set on fire, the gasoline burned, as it was on top, the remaining “alcohol” was passed through the gas mask box, unscrewing the corrugated tube, and then diluted with water and drunk. I tried it too, and this disgusting thing made me vomit. And the vodka issued was made from wood alcohol. They joked that it was made from broken stools. From then until today I don’t drink vodka at all. Champagne, good grape wine or a glass of cognac at a party or when we have guests, I drink one, sometimes two glasses in small sips per evening, but no more. My friends laugh and call me a “defective sailor.”

The Neva was covered with ice, the frosts were getting stronger. In order not to freeze the ships completely, we were ordered to move to Leningrad. I was assigned a place near Babushkin’s garden, opposite the Lomonosov porcelain factory and the Vienna brewery. The Lomonosov plant made sapper blades, knives and grenades for the army, and “Vena” brewed beer from burnt grain from Badaev warehouses set on fire by incendiary bombs from German planes. This burnt grain was no good, it was impossible to cook anything edible, and the beer turned out to be bitter, but quite decent.

Once the directors of the Lomonosov and Vena factories came to my ship and asked for permission to take a shower.

Of course, I allowed it and treated him to carrot tea in the wardroom. The directors asked if I could provide them with electricity for production; they did not have autonomous electricity, and the city electricity was completely turned off throughout the city. I replied that I could provide 20 kilowatts, but I have almost no coal. The director of the Lomonosov plant said that he had coal and could give it to us. In short, wires were stretched across the road, or rather, across the embankment, and I began to give them electricity - the factories started working. And “Vienna” gave me a barrel of beer every day for this - this is an enamel mug for each member of the ship’s crew. For half-starved people this was a great help.

On January 14, 1942, by order of the fleet commander, I was appointed commander of a division of network minelayer ships as part of new, specially built ships for the installation of anti-submarine networks “Onega” and Vyatka - a non-self-propelled network barge, the minelayer “Izhora” and the former Estonian wheeled minelayer “Ristna” " There were only five units, all of them, except for the Ristna, were stationed at the ship repair plant opposite Smolny, where the front headquarters was located. My replacement, removed from the minefield “Marti” for some offenses, captain of the 2nd rank Abashvili, arrived at the “Leningradsovet”. I took the parting with “Leningradsovet” hard, and both the officers and sailors, if I dare say, were sad too. We have experienced a lot of grief together.

He arrived at Onega - the ship was the flagship of the division - and began service. I went to “Ristna”, it stood on Malaya Nevka behind the Lenin Stadium, on the Petrograd side near the “Red Bavaria” beer factory. I was “lucky” to visit breweries. I didn’t like the ship itself: big, wheeled, clumsy, but the commander and crew were good sailors and loved their ship, and this is very important in the service, when there are such concepts as loyalty and confidence that we will stand and Leningrad will not we'll rent it out.

The ships were at the ship repair yard. We chipped off the ice so that the hulls would not be crushed, camouflaged the ships with fishing nets and piled mountains of snow and ice almost to the height of the sides to make it difficult to bomb German planes, which daily (usually in the evening) in groups of 20-50 Yu-87 bombers, “Yu-88” bombed the city, bridges, Smolny and just residential buildings. In the air, our fighters conducted air battles, and our ships were assigned a sector in which we fired with naval weapons.

This winter was very difficult for Leningraders. Many died of hunger. Not far from where we stopped was the Okhtinskoe cemetery, where barely alive people on children's sleds dragged the corpses of the dead wrapped in rags across the Neva across the ice; often the person dragging them died and remained lying in front of the sled. Every morning, the sailors of the ships picked up dozens of dead people from the ice and delivered them to the shore of Okhta.

But most of all, the children upset us to the point of tears. They knew when it was lunch time on the ships, they came up to the ships in crowds, clung to the side with their frozen hands and cried and asked, holding out mugs: “Uncle, give me something, at least a little,” - and in our cabins they lay swollen from hunger sailors. He ordered the supplied flour, from which the “soup” was made, to be diluted thinner, and a little was poured into the children’s mugs. And they, happy, having sipped a little, carefully carried the remains of the soup home to their mothers and relatives who could not get out of bed.

And now, when I write these lines, the faces of these children “stand” in front of me, a lump rolls up in my throat, and goosebumps crawl down my back. The Leningrad siege survivors are true heroes, many know this from books, poems, newsreels, but I saw it with my own eyes. I saw their unbending will to defend Leningrad. I saw stacks of corpses in a vacant lot where Piskarevskoye cemetery is now. I saw how sappers made holes with explosions, and bulldozers raked these piles of corpses in them.

In the spring, fearing an epidemic, at the call of the city leadership, everyone who was still moving took to the streets and cleaned up the dirt. I saw how my sister on the embankment near the NKVD house with her colleague from the pharmacy together lifted an iron crowbar and chopped ice on the sidewalk, freezing for a few seconds after each blow, but they beat and beat, exhausted from fatigue.

In the summer, in June, I was ordered to install anti-submarine nets near the island of Lavensari - this is 150 kilometers from Leningrad in the Gulf of Finland. There was a Baltic Fleet base there, from where, having completed their last refueling, the submarines departed for the Baltic Sea and surfaced there when returning. We set up nets, leaving corridors for our returning ships and submarines. But the warning was not established and the next day one of the boats climbed into our nets and was blown up by explosive cartridges suspended on them. Thank God, the damage was minor, and the boat was quickly repaired at a floating factory on the island. Nets were repeatedly installed along the line between the Shepelev lighthouse and Bjerke Island. I commanded this division until April 1943.

10th patrol boat division.

I was appointed commander of a division of minesweeper boats, which were converted into smoke-screen boats. We removed the mine sweeping winches and installed two DA-7 smoke equipment at the stern, operating on a mixture of sulfonic acid and water. A DShK (large-caliber) machine gun was placed on the nose. The division also had boats with twice the displacement, metal ones with 25-mm cannons on the bow, and self-propelled ones with ZIS engines, and tenders for transporting barrels of sulfonic acid for refueling boat equipment. Each boat, in addition to the smoke equipment, had another 20 MDKB bombs (marine smoke bomb). In total there were about 30 units in the division. “About” because boats were lost while carrying out missions, as I will discuss below.

As the flagship boat of the V.F. Tributs gave me his duralumin, well-equipped high-speed one, with a speed of 30 knots, with four GAM-34F aircraft engines. The division received the name “10th division of smoke-screen patrol boats” of the Baltic Fleet (10th DSK). The need for such a connection was that our ships, convoys, submarines, traveling to Lovensuri on the surface due to the shallow depths, when leaving Kronstadt immediately behind the Tolbukhin lighthouse, ended up

under fire from coastal batteries from the Finnish coast - guns 180, 203, 305 and even one 14-inch (340 mm). It was necessary to protect our convoy ships going to the islands of Seskor, Lavensari, and Gogland. It should be taken into account that at that time there were no radar sights. Covering the targets with a smoke curtain made shooting useless. The task of the 10th DSK was, following between the Finnish coast and the convoys, seeing flashes of gunfire from the boat, to set up a smoke screen - this impenetrable wall along the entire length of the convoys did not make it possible to conduct aimed fire, and the enemy stopped firing. The boatmen became so skilled that the enemy, as a rule, did not even have time to see the fall of his first salvo. The situation was worse when there was a strong wind from the north, the smoke was quickly blown towards our shore, and targets were revealed. In these cases, the boats had to follow as close to the batteries as possible. Then the enemy fire was transferred to the boats, they were hit with shrapnel shells, and the division suffered losses. Well, when it became unbearable, then at the signal “Everyone suddenly 90° to the left,” they temporarily went into their own curtain, knocked down the aimed fire and again went to their places. And so every night. Some of the boats, from three to ten units depending on the length and importance of the convoy going to the islands, went out to cover it. The other part is to cover transport ships traveling from Kronstadt to Leningrad, from Lisiy Nos to Oranienbaum. The Germans were in Peterhof, Uritsk, at the typewriter factory, and the front line passed near the Krasnenkoye cemetery, this is next to the Kirovsky factory and my house. By morning, all the boats returned to Kronstadt to the Italian Pond - in the depths of the Merchant Harbor. There was a hut on the shore; it was the division headquarters, a galley, and a warehouse for barrels of sulfonate, smoke bombs, and gasoline. As soon as they returned, they immediately sent the wounded to the hospital, washed the boats, refueled the equipment with sulfonic acid, replenished ammunition, took smoke bombs until they were full, refueled with gasoline, and then had dinner and went to bed. We lived on the boats until late autumn, when the blankets began to freeze to the sides. And all this was almost under the balcony of the Fleet Commander’s office, and when the fleet headquarters moved to Leningrad on Peschanaya Street in the building of the Electrotechnical Institute, then the Chief of Staff of the Kronstadt Defense Region, Rear Admiral Vladimir Afanasyevich Kasatonov, came out onto the Fleet Commander’s balcony, with whom, in addition to official matters, I also had personal friendly relations. He was a wonderful man. The headquarters or, rather, the management of the 10th DSKD was staffed with excellent officers - Burovnikov, Filippov, Selitrinnikov, Raskin, chemist Zhukov, Doctor Pirogov, communications officer Karev and smart, well-mannered Ivan Egorovich Evstafiev (he was the deputy division commander for political affairs). He was the only political worker whom I deeply respected until the last day of his life. One day before going to bed I asked him:Ivan Egorovich, how come the Germans won’t understand that their racial theory is stupid? Recognize only Aryans as people, and burn Jews, Armenians, Georgians, Muslims in ovens?

Ivan Egorovich answers:

Nikolai, you must understand that for the Germans, fascism and Hitler are the same as communism and Stalin for us.

An extremely simple and extremely clear answer to the question posed. Ivan Egorovich died in Riga from stomach cancer and was buried there. Eternal memory to him. His family - his wife Valentina and two daughters - still live in Riga. With the collapse of the USSR, I lost contact with them.

The commanders of the boats were foremen, most of whom were called up for mobilization. Experienced sailors, devoted to the Motherland and their people - Berezhnoy, Pavlov, Mikhailovsky, Pismenny, Korol. Can you really list them all? About forty officers passed through the division. All of them were fearless and with their courage they set an example for all personnel. I remember that the boats were covered by destroyers traveling from Kronstadt to Leningrad. The Germans opened heavy fire on them from Old Peterhof, Martyshkino, Uritsky, and the typewriter plant. The boat set up a smoke screen; the boat with the detachment commander, Lieutenant V. Akopov, was leading. The boat was hit by a six-inch shell and was blown to pieces. A window appeared in the smoke curtain. It was closed by a boat heading into the wake under the command of Ivan Benevalensky. The destroyers had already entered the fenced part of the Leningrad Canal, the boats began to retreat, dropping smoke bombs onto the water. A shell exploded near Benevalensky's boat, the boat received many holes in the hull, the helmsman, signalman, chemist, and machine gunner were killed. Only the mechanic remained unharmed, and the commander was wounded in the legs and chest. Benevalensky, seriously wounded, crawled to the stern, turned on the smoke equipment, then somehow climbed onto the bridge, took the helm in his hands and, lying down, brought the boat to Kronstadt, where we learned about what had happened. I remember well another battle; it took place already in 1944, when the troops of the Karelian Front liberated the city of Vyborg. I was ordered to take an army battalion in Ololakht Bay and use boats and tenders to land it on the islands in Vyborg Bay. When planning the operation, Vice Admiral Rall decided that it was impossible to start from Bjerki Island: there was a large garrison and a 180-mm battery there. It was necessary to break through into the bay between Bjerke and the village of Koivisto, which was already ours, to land troops on the island of Peysari, capture it, and then, having crossed a small strait from the rear, take Bjerke. In the dark night we loaded up the troops and, guarded by three skerry monitors and three torpedo boats, in readiness to set up a smoke screen if we were discovered from Bjerke Island, we safely passed through the Bjerke Sound, Koivisto Strait and landed troops on Peysari Island. In the morning, four large German landing barges (LDBs), each armed with four 4-barreled 37-mm artillery mounts, appeared from the depths of the Vyborg Bay, and began to “water” us with shells, like water from hoses. The boats began to depart to the village of Koivisto; we could not return to Ololakht Bay, since the Finnish gunboat Karjala appeared in the strait. The boat under the command of Nikolai Lebedev approached the BDB. Nikolai Lebedev was seriously wounded. Midshipman Seleznev directed the boat to our shore, and when the boat ran aground, he took N. Lebedev in his arms, jumped into the water and carried him to the shore. But a shell hit him in the back, and both he and the commander died. Our patrol ships of the “Bad Weather” division - “Tempest”, “Storm”, “Cyclone”, “Smerch” - arrived. After a short battle, the BDB and the gunboat left. The ships sent a marine regiment to the Koivisto area and took the islands of Bjerke, Melansari, Tytensiare and all the others in the Vyborg Bay. The 10th Division buried Nikolai Lebedev and all those killed on the shore near the village of Putus. After the war, the local authorities of the cities of Example k (former Koivisto) and Sovetsky (former Tronzund) reburied all individual graves. A monument was erected on Primorsk Square.

Every year on June 22, we, the survivors, are invited by the mayors of these cities to honor the memory of the dead. But every year there are fewer and fewer veterans, and travel is now unaffordable for many. To finish the story about the 10th division, it should be said that in the winter, during freeze-ups, when the boats could not sail, from the boat crews we formed crews of skimmers on the snowmobiles provided to us, along the sides of which we placed metal canisters for four MDS, and pipes from the canisters brought to the propeller. The snowmobile commanders were the boat commanders, the navigators were the helmsmen, the machine gunners were the machine gunners, and the chemists were in charge of the smoke. It was on these smoke-curtain snowmobiles that we covered the transfer of the 2nd Shock Army of Lieutenant General I.I. Fedyuninsky from Lisy Nos to Oranienbaum to lift the blockade of Leningrad. After the capture of the islands in the Vyborg Bay, the division was awarded the Order of the Red Banner and became known as the “10th Red Banner Division of Smoke Curtain Patrol Boats - KDSKDe,” and the division commander was awarded the Order of “Admiral Nakhimov.” I remember this division and my comrades with great respect and pride. Some people still write letters to me.

4th Mining Brigade of the Red Banner Baltic Fleet

In the early spring of 1945, I was called by the fleet commander, Admiral V.F. Tributs announced that the Military Council, considering personnel issues, decided that I had served enough in the 10th Red Banner Division of patrol boats. The Fleet Commander came up to me, tapped his finger on the “Admiral Nakhimov” order and said:

Well, how did you fight - that’s an assessment! We have decided to appoint you as chief of staff of the KMOR (Kronstadt Maritime Defense Region) trawling brigade.

The brigade commander, Admiral Mikhail Fedorovich Belov, is already in his old age, and you are young and I will have first of all demand from you.

The conversation ended there. Soon the order for my appointment arrived.

I came to Oranienbaum and introduced myself to the brigade commander. Mikhail Fedorovich Belov looked at me critically and said:

Young, but they told me he was lively. Well, get down to business, the brigade is large, and the Germans and hundreds of thousands of us laid mines in the Gulf of Finland.

Mikhail Fedorovich was a kind person by nature, very punctual in his work. Having looked closely at me, he began to trust and support me completely and in everything. At first, of course, it was hard - this was a new thing for me, and there were a lot of ships and people. But I was young and tried to justify the trust of Mikhail Fedorovich.

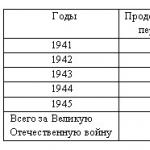

We understood that shipping was essentially paralyzed, but the personnel of the ships did not take into account the difficulties and dangers of combat trawling. They trawled day and night in order to break through safe fairways for navigation as quickly as possible. This was very important for the country's economy, the normal operation of commercial shipping and ports.

May 9, 1945 is Victory Day, and for the personnel of minesweepers and minesweepers, the war ended only around 1950-1953. In the spring and summer of 1945, our brigade cleared up to one thousand mines per day. Of course, we suffered losses, minesweepers were also blown up. The command of the Kronstadt region, Vice Admiral Yuri Fedorovich Rall closely monitored the activities of the brigade, and the chief of staff of the region, Rear Admiral Vladimir Afanasyevich Kasatonov (his son Igor - now admiral, 1st Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Navy) was often in the brigade with his advice and demands , of course, helped both in planning and in providing material needs.

We dealt with anchor mines successfully. They also dealt with the defenders of the minefields - these are mines placed by the Germans at a shallow depth from the surface of the sea. Instead of a minral (cable), they used chains (which could not be cut with ordinary trawl cutters) so that the mine did not float to the surface, where it could be destroyed, usually by shooting from cannons. They found a way out: they began attaching TNT packets to the trawl cutters, which broke the chains. This was carried out by shallow-draft boat minesweepers, and behind them came large minesweeper ships with wide-width trawls and cleared mines placed against large ships.

But we also encountered a German innovation - electromagnetic mines, which were used en masse at depths of 10 to 40 meters, including in ports and harbors even in the absence of fascist troops. “KMN” mines were a wooden box on wheels the size of a cubic meter filled with explosive

substance TGA (TNT-hexogen-aluminum). The explosion power of this substance is 1.6 times greater than that of TNT. Inside the mine there was a very complex mechanism with an urgency device for bringing the mine into combat position (from immediate to one month) and a multiplicity device (from 1 to 16), which reacted to a certain passage over the mine or near its ship or vessel. The initial sensitivity of the mine was 4 milliersteds (0.31 a/m). Over time, the sensitivity became rougher, and given that the vessel (ship) creates a field of several hundred milliersteds, these mines could be dangerous for several years, as I was convinced of later.We did not have any trawls against such mines. Ships and vessels were blown up in fairways carefully cleared of anchor contact mines. The only thing we came up with was to use a small wooden minesweeper towed 500 meters long to drag a large metal barge loaded with rails and scrap metal to create a large magnetic field. Mines, as a rule, exploded in front or on the sides of this barge, but the minesweeper remained intact. But, of course, there were losses. And when these losses became frequent, they began to drag these barges side by side (the minesweeper was moored close to the side of the barge). There were cases when mines exploded very close, and both the minesweeper and the barge were lost. To consider a strip to be trawled, it had to be walked along it 16 times.

All science was “put on its feet,” or rather, “on its head.” Academicians A.P. Aleksandrov - in the Baltic, I.V. Kurchatov - on the Black Sea. But there was no time to wait for results. The Baltic was needed by the national economy. For the sake of fairness, it should be said that academicians created special devices that measured the magnetic field of ships leaving the harbor and at special stations they reduced the ship’s magnetic field, and then mounted a cable winding on the ship along the entire perimeter of the hull, but this did not solve the problem. The cruiser "Kirov", which had such a cable demagnetization device, was blown up by a "KMN" mine - the bow of the ship was torn off.

To the People's Commissar of the Navy I.G. Kuznetsov learned that our allies, the British, have an effective special trawl against electromagnetic mines. And by his decision he exchanged the RAT-52 torpedo (put into service in 1939) for this trawl, for which he subsequently paid in court of honor. So, we got the trawl. It consisted of two cables - one shorter, the other longer, at the ends of the cables - five copper rays, thus, in salt water, a strong electromagnetic field was created between the electrodes (long and short cable). On the ship, a special device measured the electric current supplied to the cables, changing its polarity - plus or minus. Due to the small width of the trawled strip, it was advantageous for trawling to be carried out by two ships equipped with “LAP” trawls (the name of English trawls) moving in front line formation. Having received these trawls and installed them on two minesweepers (sea tugs in the past), we went to test the fairway in the Krasnogorsk roadstead near Kronstadt. I was present at these tests together with Academician A.P. Alexandrov. The ships lined up in front, gave the command “Turn on the current,” and immediately 11 mines exploded in front of us, on the sides and even a few from the stern. It was a stunning sight. We turned off the trawls, reeled in the views, and returned to Oranienbaum. We sorted out the results and determined the procedure for using such trawls. Thus, a large state task began to be solved faster. The fact is that these trawls and subsequently the LAP trawls, with which the six American UMO minesweepers received by our Lend-Lease brigade were armed, and our domestic trawls, created on this principle, but more advanced, did not require 16-fold passage at the same place. Everything was resolved in one pass. To be sure, sometimes two passes were made. And more about the “KMN” mines. As you know, in 1955, the battleship Novorossiysk (formerly Italian Giulio Cesare) was lost in Sevastopol Bay. The cause of death has not yet been clarified; there are many versions. I am convinced that the battleship was blown up by the KMN.” My beliefs are based on additional information I received when I became a brigade commander.

A brigade of ships protecting the water area of the Riga base.

I was appointed commander of this brigade in the spring of 1949. It consisted of several divisions of minesweepers, patrol ships, anti-submarine ships and boats. The brigade was based at the mouth of the Western Dvina, 15 km from the city of Riga, in the village of Bolderaja. They carried out patrol duty, cleared mines in the Gulf of Riga, and exercised control over shipping. During the naval parade on Navy Day on the Daugava River, directly in the city center, I received a report that a dredger dredging the commercial port of Milgravis, 5 km from the city down the river, scooped up some large object similar to for a minute. The dredging team swam to shore. Having finished walking around the ships of the parade, I, in a ceremonial uniform, with orders and a dirk, in patent leather boots, white gloves, with the consent of the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of Latvia Vilis Latsis and the Chairman of the Supreme Council of Latvia Kirkhinstein, Secretary of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR Gorkin, who were present on the parade boat, moved to the spare boat left for Milgravis. Approaching the dredge, we found a hanging, slightly damaged KMN mine hanging in one of the buckets. They called in sailors from the brigade, including mechanics who knew how to operate cranes. On a tarpaulin, like a baby, the mine was carefully lowered onto a boat, taken out to the Gulf of Riga, pulled ashore and detonated. The explosion was so strong that in the neighboring villages of Ust-Dvinsk and Bolderaya, glass flew out of houses. I was presented with a colossal bill, but the leadership of Latvia, with whom I had very good friendly relations, took me under protection and paid all the expenses for the damage caused. Vilis Latsis even gave me his autographed collection of works. This incident set us a new task - to check the entire river bed from the city to the exit to the bay. Trawling is not allowed - this is a feature of the city, port, villages. Explosions on site could cause extensive damage. We decided to inspect and search for mines at the bottom with divers (this is 15 kilometers from the railway bridge in the city center to the exit to the Gulf of Riga). We formed groups of boats with divers and began work. Not without success. In total, we found, recovered and destroyed about 100 mines in safe areas. I also had a chance to participate in the neutralization of these mines. We established the presence of a hydrostat in the mechanism, onto which a secondary fuse detonator was “put on” at a depth of 10 meters. At a depth of less than 10 meters, the hydrostat did not work (low pressure), and although the urgency and multiplicity device and the fuse worked, the mine did not explode. Such mines were not neutralized by any trawls. In addition, in the complex mechanism of urgency and multiplicity instruments there is a lot of soldering and in some of them the clock mechanisms became clogged. There were cases on the Daugava when a diver cut off a mine to lift it, moved it, jumped to the surface and gestured: “Hurry up, lift it, it’s starting to tick!” This means the clock has earned. Such mines were quickly lifted out of any queue and towed at full speed to the explosion site. There were several cases when we didn’t have time to get there and it exploded on the way. But, thank God, there were no deaths.

Now let's return to Sevastopol. The Germans, retreating, randomly scattered NMN mines in the harbors, including in Sevastopol Bay. My belief that the battleship “Novorossiysk” was blown up by the “NMN” mine is based on the fact that when she returned from the sea and anchored, she either moved the mine with her hull or the anchor chain, the clock started working, and after some time an explosion occurred. The hole received by the battleship is similar to the holes from KMN. And the ship capsized because, having touched the ground with its nose, it lost stability. If the harbor had been deeper, it would have floated like a float. A similar incident occurred with the large tanker No. 5 in the Gulf of Finland back in 1941. Remembering my service in the OVR brigade of the Riga base, I would like to talk about my meeting in Riga with Nikolai Gerasimovich Kuznetsov, when he, removed from the post of People's Commissar of the Navy, demoted to rear admiral, in 1948, was resting in a sanatorium on Riga coast in the town of Majori.

One day he called me on the phone from the sanatorium:

Nikolai Nikolaevich, could you send me a small boat to Majori with a helmsman who knows the Lielupe River well (it goes along the Riga coast), I want to walk along the Lielupe, enter the Daugava River, walk along it to Riga, see the bay, the trading port in Milgraves and return back.

I answered him that there would be a boat, and I myself would come to Majori on it, take him and show him everything he wanted. Nikolai Gerasimovich began to object, making it clear that he did not want to tear me away from work and rest (it was Sunday). I explained to him that I consider it an honor to meet and talk with him again, there may not be another opportunity. As for the boat, I will be on it myself, I know how to drive it, I know the rivers, it will be just the two of us - he and I. After some embarrassment N.G. Kuznetsov agreed with me and asked me to wear civilian dress.

We visited all the places that interested him. I acted as a tour guide - I was familiar with the area. We talked a lot about everyday affairs and, of course, about the fleet, its current state and future development.

After a three-hour swim we returned back along the Lielupe River. Nikolai Gerasimovich said that he had an idea not to go to Majori, and asked to be dropped off in the village of Dzintari, from which he wanted to travel to Majori by train (this is one stop). We approached the pier, then went to the Dzintari railway station. According to the schedule, there were 15 minutes left before the train arrived.

Nikolai Gerasimovich said that he was very thirsty. The weather was hot. I suggested that he go to the station cafe; we had enough time. He agreed. When we entered this cafe-buffet, we found that all the tables were occupied by naval officers (the rehearsal for the parade in honor of Navy Day had just ended). We stopped hesitantly at the entrance. After some confusion, the officers, as one, stood at attention, fixing their gaze on Nikolai Gerasimovich (let me remind you, he was in civilian clothes). He was embarrassed, thanked the officers and invited me to go to the platform.

We left the cafe, he stood on a hillock and fixed his gaze on the sea. We stood there in silence until the train arrived. They said goodbye and he left for Majori.

I described this episode in order to show how much authority was enjoyed in the fleets by the outstanding naval commander, great statesman Nikolai Gerasimovich Kuznetsov, a fair, caring, tactful person who knew how to listen carefully to everyone, from the sailor to the admiral, and then calmly, without haste, but clearly express your judgment.

From January 1952, I became the chief of staff of the 64th division of water area security ships, and a year later - the division commander. The fleet was commanded by Arseny Grigorievich Golovko. We were in Baltiysk (former German submarine base in Pilau) - 50 km from Kaliningrad (Konigsberg).

The division's tasks are the same - primarily mine sweeping, patrol service, combat training of personnel and development of the territory and construction of the division. They built a barracks, an open-air cinema, and observation and signal posts. On the previously destroyed tower on the bank of the entrance canal, a point was installed to monitor and regulate the movement of ships and transports traveling along the Baltiysk-Kaliningrad canal. And, of course, the restoration of a city destroyed by war.

1963, on the bridge of the EM "Skromny", Atlantic, ship's watch officer

« I am Gennady Petrovich Belov, born in the city of Leningrad on May 11, 1937, and in my childhood I saw hunger, cold, horrors and fear of war and human participation…»

For me, these lines of the writer’s autobiography are key. Here is the source of this man’s courage and faithful service to the Fatherland, the special care and delicacy that he shows towards his heroic fellow soldiers, towards those who shared with him the years of service in the Navy, regardless of ranks and titles. His heightened sense of justice comes from his childhood during the siege. Therefore, with such tenacity, he strives to perpetuate the memory of those who dedicated their lives and destinies to the defense of their country, and to understand the causes of the tragic events in the fleet, which exposed global destructive processes in society.

1966, on the bridge of the EM "Fire", White Sea, ship's watch officer

Gennady Belov is a retired captain of the first rank, a member of the Russian joint venture, and served in the navy for more than thirty years, eighteen of which were devoted entirely to the Northern Fleet. A man filled with love for Russia, he devotes his “civilian” life to his life’s work - serving the Fatherland.

Today, after more than twenty years since the collapse of the great country, against the backdrop of the monstrous events in Ukraine and the unprecedented campaign of persecution of Russia from Europe and the United States, books about Russia’s only allies, in the words of Emperor Alexander III - its army and navy - are being purchased special meaning, relevance and value.

Gennady Belov's literary account includes several unusual voluminous books. The debut, “Behind the Scenes of the Fleet,” was entirely dedicated to naval service in the 60s and 70s. Belov edited her manuscript about forty times, the first part was published in St. Petersburg in 2004, and the second, expanded edition was published in 2006. The narrative vividly recreates the special spirit of the military and peaceful life of the Soviet naval officers. This book is a kind of part of the chronicle of the history of the Northern Fleet from 1959 to 1977. Prominent representatives of the command staff - Vice Admiral E. I. Volobuev and Rear Admiral E. A. Skvortsov - are the heroes of his other book, “Honor and Duty,” published in St. Petersburg in 2009. The characters of outstanding military leaders, with whom the author was associated with long service in the Northern Fleet, and with E.I. Volobuev - also sailing in two military services, are written out laconically and precisely. The simplicity of the narrative makes the book unusually concentrated, strict, and capacious. You read and involuntarily envy: Belov was lucky in his life to meet real people! He understands the importance of everyone’s extraordinary individuality, he sincerely admires his commanders, admiring their courage and professionalism, their demands - first of all, on themselves.

November 1969, head of the RTS at the Sevastopol BOD

And “Extreme Navy Lexicon” is a brilliant chapter that deserves special mention. We do not even suspect that many of the “iconic” catchphrases of recent years were borrowed by our contemporaries from the monologues of outstanding leaders of the Soviet fleet. The chapter contains statements by the commanders of the Seventh Operational Squadron at headquarters briefings, meetings and debriefings, recorded by headquarters officers and Gennady Petrovich personally. Bitter, specific humor, steeply mixed with the details of naval realities, in the mouth of a commander with remarkable intelligence and erudition, is a special “weapon” and, of course, a separate branch of oral folk art. Many of these expressions, picked up by the Internet, can be said to have become national property.

I would like to pay special attention to documentary photographic materials: the book is equipped with a large number of unique photographs. Have you noticed how strikingly different the faces in old photographs are from living ones? Smart. Brave. Clear. And always - extraordinary!

1968, Yalta, Massandra, with Evgeny Evstigneev after filming the film “Strange People” by Vasily Shukshin

However, the most significant in the work of G. P. Belov is a historical and literary work - the 600-page “Atlantic Squadron”.

“The book about the Seventh Operational Squadron of the Northern Fleet is dedicated to describing the historical events of its formation and combat activities from the beginning of its formation to the last days of service in the Navy. It fully presents statistical data of all stages of the squadron’s combat activity, describes the creation, construction and development of ships of the latest projects. The described episodes of events during combat service enable all readers of the book to understand that at the forefront of protecting the interests of our Motherland were dedicated admirals, officers, midshipmen and ordinary sailors. All of them showed courage in the most difficult situations in ocean voyages and successfully completed their tasks even in the difficult conditions of the inhospitable Atlantic. In addition, the author makes an attempt to analyze complex processes in the work environment on the squadron and writes about the difficult fate of ship commanders. Unfortunately, a complex historical process expunged the squadron from the Navy, but the rich experience of the squadron in defending the geopolitical interests of our Motherland shown in the book gives hope that it will be in demand by a new generation of sailors, and this is precisely the value of this book,” writes in the preface to it the Chief of the Main Staff of the Navy, First Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Navy of the Russian Federation (1996-1998), Admiral I. N. Khmelnov.

I am sure that not only “new generations of sailors” may be interested in “The Atlantic Squadron,” but also any reader who is passionate about the history of Russia, its military glory and the eternal “maritime” theme.

1966, EM "Fiery", behind a tactical tablet

Only an impartial document painlessly allows for excess. In a work of art, the abundance of “demonstrative” heroics causes a smile. The documentary material speaks for itself. You can internally resist as much as you like, disagree with something - but these people were SUCH. They sacrificed themselves for the well-being of their homeland. They didn't discuss orders. We experienced enormous stress. They took responsibility not just for the strict execution of orders, for the life of the ship, but often for the fate of the world. Can we understand the extent of this responsibility? Gennady Belov knows this firsthand - the author had to undergo six combat services during his service in the 170th brigade and the Seventh Squadron!

The events in Panama, the extreme stress of our sailors during the conflicts of 1967, 1973 and 1986, the war in the Persian Gulf, the rescue of civilians in the front-line zones of Africa - the crews of the squadron ships defended the geopolitical interests of the USSR, brilliantly carrying out the most complex combat missions in exercises, in every possible way restraining the activity of the US and NATO naval forces in the confrontation in the vast Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea. After all, our most popular, simply set sore throat, post-war slogan was “Peace to the world!”, and in the West they did not intend to “coexist peacefully” for a long time.

1959, 5th year cadet of the Higher Naval Radio Engineering School (VVMIRTU)

The book “Atlantic Squadron” by Gennady Belov is, of course, a colossal memoir-scientific work, priceless and timely. Even the “Contents” are compiled in the likeness of a dissertation: chapters and subchapters, a glossary of terms, a list of references - more than 120 sources. Rare photographs, a complete list of ships of the squadron with all output data. An extensive, scrupulous study, in the work on which Belov managed to involve a large number of people, and Belov, by the way, did not forget to express gratitude to each of them in the “From the Author” address.

In essence, this book by Belov is a monument. A granite sculpture of words and meanings. Severe, heavy, devoid of frills, “ornaments”, all sharp corners - but real, for centuries!

Of course, it’s hard to read through the pages devoted to negative episodes in the fleet that resulted in human casualties - accidents, fires and flooding, often provoked by elementary bungling, the incompetence of individual team members, abuse of power, or the stubbornness of the command. Sometimes it seems that these numerous facts outweigh the pages filled with deep respect for the military hard work and feat of Soviet sailors, telling about courage and dedication, excellent performance of combat missions. However, we have facts before us. There is no hiding from the truth. The time has come to look it in the eye, evaluate the past impartially, and in the future, nurturing the best, try to avoid fatal, repeated mistakes. After all, the processes that led to the destruction of the Squadron also led to the disappearance of a huge power from the political map of the world! Today is the time to “gather stones.” The time of opportunistic overthrow and denial of the achievements of the past has finally passed. In light of the latest violent events, when the “world community” is frantically condemning Russia for the sins it has not committed, a great people has been slandered, driven into a severe inferiority complex, destroyed by various kinds of “reformers” and enemies throughout the 20th century, consisting of those same epic “quilted jackets” , “Colorados”, “Soviet” - gets up from his knees!

1959, College graduate

“Kyiv” - how painful it is to pronounce this word today. But with this glorious name a new era in the navy began. On July 21, 1970, the first Soviet aircraft carrier, named Kiev, was laid down on the zero slipway of the Black Sea Shipyard No. 198 in Nikolaev. The fate of this ship was symbolically determined. The whole country built Kiev. 169 ministries and departments, over three and a half thousand major enterprises took part in its creation. To inspect such a ship and visit each room for at least one minute, it was necessary to spend more than two and a half days of pure time. It became a breakthrough in domestic shipbuilding in many areas, but most importantly, the fleet for the first time received an aircraft-carrying ship with deck-based aircraft on board. "Kiev" was launched on December 26, 1972, and on August 28, 1994, the handsome aircraft carrier was SOLD to a private company in China and on May 20, 2000, it was taken by the tugboat "Daewoo" to Shanghai, where it was converted into a floating tourist entertainment center ...

By the beginning of the new millennium, through the efforts of the perestroika destroyers, Russia surrendered its battle fleet. Most of the ships, not having served even half their operational life, were sold for next to nothing for scrap metal to China, Turkey, South Korea and India. At the same time, the author emphasizes, even secret equipment was not removed from the aircraft carriers during the sale. Less than 30 million dollars was received for the sale of a giant armada of ships, but the construction of one destroyer costs ten times more! G. Belov bitterly summarizes: “E. A. Skvortsov rightly said in his book “Time and Fleet”: “Probably in Russia, in addition to bad roads and fools, there are also criminals.” Certainly. We even know them by name - the inspirers, “foremen” and generals of perestroika! So many years have passed, and the author’s heart is still filled with inexplicable bitterness when he lists the ships that have left the fleet: “ Be patient, absorbing every line, read this memorial list of our fleet, our power, our strength, our pride, our national respect, our strength, money, sweat, mind" The pain-filled pages of Belov’s book, dedicated to the last days of the squadron, are a high Requiem, no less strong and spiritual than the famous song “Varyag”. And farewell to the squadron here also reads quite symbolically - it is also a farewell to the past: to the country, to one’s destiny, to life itself, because the deliberate death of the squadron entailed crippled destinies.

Third course. In the photo in the middle. On school boats

« The news of the liquidation was tragic for many officers. The squadron had a 37-year history of existence. A high staff culture was developed, which was passed on from generation to generation, and any officer coming to the squadron headquarters adopted this spirit of high dedication and professionalism. The connection management organization was created and perfectly worked out. This is the invisible thing that is created and developed over many years of hard work. And suddenly all this was destroyed in an instant. Who needed this and why? The leadership of the country and the Armed Forces have once again brought the Navy to its knees. The origins of this decision and the actors involved are unknown, and even now no one will dare to reveal the whole unpleasant truth. But I’m sure that years later they will write about this and name the characters involved in this naval tragedy. The time for history has not yet come..."

In the works of Gennady Belov there are no linguistic delights, no dashingly twisted plot, no old-testament sea reckless romance, they have completely different tasks and goals. Here is life. Severe, sometimes comical, sometimes inglorious, and more often heroic. Life without embellishment, which is more fantastic than any fantasy and more dramatic than any Shakespearean tragedy. Just look at one episode of the squadron passing through the “eye of the cyclone” - a 7-point killer storm, unfortunately, as selfless as it is completely useless, not motivated by anything other than the tyranny of the higher authorities...

And what courage was shown by the commander of the Zhguchiy BOD and the entire crew, who, in order for the ship not to lose speed in a severe storm, manually scooped fuel from the bottoms of the tanks when its automatic supply ended. The actions of Captain 2nd Rank A.A. Kibkal evoke admiration: in order not to risk the lives of his subordinates, he, being on the brink of death, himself cleared the mines of a GDR cargo ship in the port of Luanda. A real feat was accomplished by the commander of the EM "Experienced" - Captain 2nd Rank Yu. G. Ilyinykh, who went to sea to free representatives of the Angolan authorities taken hostage, without permission from the Navy command (there was no time to wait).

Battleship "October Revolution"

“Atlantic Squadron” unfolds a grandiose three-dimensional panorama of the complex life of the fleet, unknown to civilians, where behind the luxurious, proud, chiseled silhouettes of warships lie the fates of not only admiral commanders, captains, first mates, midshipmen, sailors, but also the entire country.

After reading the “Atlantic Squadron” by Gennady Belov, I catch myself thinking that its realities, a southerner, suddenly became close to me and the roads - and the harsh landscape, and the people of the Russian North, and the characters of the sailors of the northern fleet, and the unkind sky, and the icy sea, and ships.

« …My feelings? They go back many decades to my years as a lieutenant. And even now I’m ready to live in my cold, drafty, without toilet and water apartment on the street. Eastern. Despite the hardest service, I remember with trepidation Severomorsk, hikes in the generous tundra and my struggle for honor and dignity for decades. Your phrase that after reading my books Severomorsk seems like home to you made me cry like a man... It truly was a special city. For the most part, everything was fair there. Intelligent and kind people, special garrison way of life..." - Gennady Petrovich answered my letter.

The fleet is being reborn, as is our identity. The exploits of our fathers and grandfathers were not in vain, nor was the service of the Seventh Atlantic Squadron in vain. Russia was, is and will be.

This means there will be a Northern Fleet!

Olesya Rudyagina