Liberation of cities. Gorodok operation Military tribunal of the 4th shock army

Nevel offensive operation- front-line offensive operation of the Red Army against German troops during the Great Patriotic War. It was carried out from October 6 to October 10, 1943 by part of the forces of the Kalinin Front with the goal of capturing Nevel and disrupting enemy communications on the northern wing of the Soviet-German front.

Situation

German defense

German defensive fortifications in the Nevel area (December 1943)

The German defense was a system of strong strongholds and resistance centers located in terrain with a large number of lakes and deep ravines. From an engineering point of view, the defense was well prepared and included a developed system of trenches, trenches, full-profile communication trenches, as well as dugouts and bunkers with multiple overlaps. A large number of reserve positions were equipped for machine guns, mortars and guns. In the direction where the Soviet troops intended to deliver the main attack, more than 100 firing points, up to 80 dugouts, 16-20 mortar positions, 12 artillery batteries and 12-16 individual guns were located. In addition, up to 8 artillery batteries could fire from neighboring areas. The front line of the defense was covered by two strips of minefields 40-60 m deep and two rows of wire barriers. The second defensive line ran along the river. Six. The total tactical depth of defense was 6-7 km.

The closest reserves of the Wehrmacht amounted to up to four battalions and up to two infantry regiments.

Composition and strengths of the parties

USSR

Part of the forces of the Kalinin Front:

- 357th Rifle Division (Major General A.L. Kronik)

- 28th Rifle Division (Colonel M. F. Bukshtynovich)

- 21st Guards Rifle Division (Major General D. V. Mikhailov)

- 78th Tank Brigade (Colonel Ya. G. Kochergin)

- 46th Guards Rifle Division (Major General S. I. Karapetyan)

- 100th Rifle Brigade (Colonel A.I. Serebryakov)

- 31st Rifle Brigade (Colonel L.A. Bakuev)

- 2nd Guards Rifle Corps (Lieutenant General A.P. Beloborodov)

- 360th Rifle Division (Colonel I. I. Chinnov)

- 117th Rifle Division (Major General E. G. Koberidze)

- 16th Lithuanian Rifle Division (Major General V. A. Karvelis)

- Part of the forces of the 83rd Rifle Corps (Lieutenant General A. A. Dyakonov)

- 47th Rifle Division (Major General V. G. Chernov)

- 236th Tank Brigade (Colonel N.D. Chuprov)

- 143rd Tank Brigade (Colonel A. S. Podkovsky)

- 240th Fighter Aviation Division (Colonel G.V. Zimin)

- 211th Assault Aviation Division (Colonel P. M. Kuchma)

Germany

- 263rd Infantry Division (Lieutenant General W. Richter)

- 291st Infantry Division (Lieutenant General W. Goeritz)

Part of the forces of the 2nd air field corps:

- 2nd Air Field Division (Colonel G. Petzold)

To repel the Soviet offensive, the following were additionally brought in:

- 58th Infantry Division (Artillery General K. Sievert)

- 83rd Infantry Division (Lieutenant General T. Scherer)

- 129th Infantry Division (Major General K. Fabiunke)

- 281st Security Division (Lieutenant General W. von Stockhausen)

- 20th Panzer Division (Major General M. von Kessel)

Operation plan

The idea of the operation was to quickly break through the German defenses, capture Nevel with a swift attack and take advantageous positions for further fighting. Suddenness and swiftness of action were of decisive importance. Any delay could lead to the failure of the operation, since in this case the German command would have time to transfer reserves to the threatened direction and strengthen the defense.

The main role in the offensive was to be played by the 3rd Shock Army. To ensure the solution to the main task of the operation, Lieutenant General K.N. Galitsky included four of the existing six rifle divisions, two of the three rifle brigades, all tanks and almost all of the army’s artillery in the strike force. These forces were concentrated in a 4-kilometer area. The defense of the remaining 100-kilometer section of the army's front was entrusted to the remaining forces. In accordance with the plan of the operation, the option of deep operational formation of a strike group was chosen. The first echelon, intended to break through the German defense, included the 28th and 357th rifle divisions, reinforced by two mortar regiments. To develop the success after the defense was broken through, the 78th Tank Brigade, the 21st Guards Rifle Division and three artillery regiments were assigned. The reserve (third echelon) consisted of the 46th Guards Rifle Division, 31st and 100th Rifle Brigades. The operation plan included 5 stages. At the first stage, it was necessary to secretly concentrate troops intended for the offensive in the initial areas and complete the accumulation of material resources, primarily ammunition, necessary for the operation. At the second stage, the troops quickly and secretly occupied their starting position in close proximity to the front line. The third stage included artillery preparation, attack, breaking through enemy defenses to a depth of 6-7 km to the river. Sixth, ensuring the entry into the breakthrough of the development echelon of success, which at the fourth stage, with a swift blow, was supposed to capture the inter-lake defile on the approaches to Nevel and take possession of the city. At the fifth stage, it was necessary to gain a foothold to the north and west of Nevel, organize a strong defense and be ready to repel counterattacks from suitable enemy reserves.

According to the artillery support plan for the operation, 814 guns and mortars were concentrated in the breakthrough area, which accounted for 91% of all those available in the army. The artillery was tasked with destroying enemy artillery and mortar batteries, suppressing firing points at the front line and in the depths of the defense, preventing counterattacks and preventing the approach of reserves. The artillery operations were organized as an artillery offensive, in which 1.5 hours were allocated for artillery preparation and 35 minutes for accompanying the attack with a barrage of fire.

In order to prevent a strike on the flank of the advancing army of K.N. Galitsky and cover its actions, the 4th Shock Army was supposed to attack south of Nevel. The attack was carried out by the 360th and 47th rifle divisions in the direction of Lake Ezerishche and further to Gorodok. The success was to be developed by the 236th and 143rd tank brigades. Their main task was to cut the Gorodok-Nevel highway.

For air support of the troops, the 211th attack and 240th fighter aviation divisions were allocated from the 3rd Air Army. While the infantry was preparing for the attack, the pilots had to carry out bombing and assault strikes on strong points located in the direction of the main attack. In the future, attack aircraft, under the cover of fighters, were to ensure the advancement of the 28th Infantry Division and the breakthrough development echelon. In addition, aviation was entrusted with the task of providing air cover for the strike group, disrupting enemy railway communications in the Polotsk-Dretun and Nevel-Gorodok sections, and conducting aerial reconnaissance in the direction of Pustoshka and Vitebsk in order to timely detect suitable German reserves.

Preparing the operation

The front and army commands paid great attention to the careful preparation of the operation. At the headquarters of the 3rd Shock Army, all the details of the upcoming operation were worked out on maps and layouts of the area with the commanders of divisions, brigades and artillery units. In the rifle units that were part of the strike group, training was carried out on individual phases of the battle: covert exit to the starting position, interaction during the attack, overcoming swampy terrain, maximum use of the results of artillery preparation. In the 28th Infantry Division, commanded by Colonel M.F. Bukshtynovich, about 50 company and battalion exercises were conducted, where issues of interaction between infantry and artillery were worked out. Until the start of the operation, intensive reconnaissance was carried out along the entire front of the army, which with sufficient accuracy established the enemy group, its numerical composition, the system of fire and minefields.

Simultaneously with the strengthening of intelligence, measures were taken to keep the intentions of the Soviet command secret. Until the last moment, the decision to attack was known to a limited circle of people. Much attention was paid to operational camouflage. Forests were used to deploy troops in the initial areas, and regrouping was carried out strictly at night. To hide the concentration of a large amount of artillery, only one gun was allocated from each artillery regiment for shooting.

During the day preceding the start of the offensive, partisans operating in the areas of Nevel, Idritsa, Sebezh, and Polotsk carried out a series of sabotage acts, as a result of which military trains with people and ammunition were destroyed, and several enemy garrisons were defeated.

On the night of October 6, all preparations were completed. Formations and units of the 1st and 2nd echelons of the strike group took their starting position for the offensive. The artillery moved into firing positions.

Progress of hostilities

| External images | |

|---|---|

| Map of the Nevelsk operation | |

The Nevelsk operation began on October 6 at 5 a.m. with reconnaissance in force. In order to confuse the German command regarding the direction of the main attack, it was carried out on several sectors of the front. In the direction of the main attack, two rifle companies, one from each rifle division of the first echelon, went on the attack with the task of attracting enemy fire and thereby identifying new ones and clarifying the location of known firing points, artillery and mortar positions. At 8:40 a.m., guns and mortars opened fire on the German defenses. The destructive shelling of the enemy's front line, strongholds, and positions of artillery and mortar batteries continued for an hour. Then more than 100 guns hit the firing points on the front line with direct fire. At the same time, pilots of the 211th Attack Air Division launched a bombing attack on enemy strongholds.

At 10:00, the infantry of the 28th and 357th Infantry Divisions of the 3rd Shock Army rose to attack and entered the battle to capture the first trench. At the same time, the artillery shifted fire deep into the enemy’s defenses. In certain sections of the front, Soviet artillery managed to completely suppress enemy firing points, which allowed the infantry to overcome the front line on the move and start a battle in the second German trench. An hour after the start of the attack, units of the 28th Infantry Division broke through the German defenses in a 2.5 km area and advanced up to 2 km in depth. In the zone of action of the 357th Infantry Division, the German defense was not completely destroyed by artillery fire; the attackers encountered strong resistance and were unable to advance.

The offensive began successfully in the 4th Shock Army. The 360th and 47th rifle divisions also went on the attack at 10 o'clock on October 6 after almost an hour and a half of artillery and air preparation. Without encountering serious resistance, they soon captured the first lines of trenches. At about 11:30, the 236th Tank Brigade of Colonel N.D. Chuprov was brought into battle. After 20 minutes, the second mobile group, led by the commander of the 143rd Tank Brigade, Colonel A.S. Podkovsky, rushed into the breakthrough. The tank crews were tasked with cutting the Nevel-Gorodok highway.

The stubborn resistance of the Nazis in front of the front of the 357th Infantry Division of the 3rd Shock Army threatened to disrupt the entire operation, in which the main factor for success was to be the speed of the offensive. In the current situation, the commander of the 3rd Shock Army decided to use the success of the 28th Infantry Division to introduce a breakthrough development echelon into battle. The 78th Tank Brigade, one regiment of the 21st Guards Rifle Division in vehicles and reinforcement units rushed forward. Following them, the remaining two regiments of the 21st Guards Division moved on foot. The breakthrough development echelon was headed by Major General Mikhailov. Minefields and marshy areas lying in the path of the attackers greatly reduced the pace of the advance. To overcome them, sapper units were used; infantrymen literally dragged vehicles through the mud and swamps on their hands. By 2 p.m., parts of the breakthrough development echelon overcame the enemy’s defenses and soon, ahead of the retreating German units, reached the Shestikha River and captured bridges across it. The offensive progressed successfully. Individual pockets of resistance encountered along the way were suppressed by fire from ground forces and attack aircraft. The raids of enemy bombers were repelled by anti-aircraft gunners and covering fighters. By 16 o'clock the advance detachment reached Nevel. Taken by surprise, the German garrison was unable to organize resistance and the battle in the city quickly ended. After occupying the railway station, 1,600 Nevelsk residents were released from two trains prepared for shipment to Germany. At 16:40, the commander of the 78th Tank Brigade, Colonel Ya. G. Kochergin, sent a report to army headquarters about the capture of Nevel. Success was achieved so quickly that front commander A.I. Eremenko doubted the accuracy of the report. K.N. Galitsky confirmed the information with a personal report and proposed developing an offensive against Idritsa and Polotsk. But A.I. Eremenko, given the tense situation on the Kalinin Front, did not support him and ordered to consolidate the success achieved. By the end of the day, units had secured a foothold to the north-west and west of the city.

As a result of the first day of the operation, the troops of the 3rd and 4th shock armies completed their tasks and drove out units of the 263rd Infantry and 2nd Airfield Divisions of the Nazis from their occupied lines. Parrying the blow, the German command hastily began to pull up reinforcements from other sectors of the front to the breakthrough area. Starting from October 7, units began to appear in the combat area

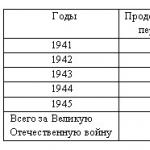

Chapter Twelve

Results of the combat operations of the 4th Shock Army

Thus, at the beginning of February, the 4th Shock Army was forced to split its forces in three directions and fight protracted battles with fresh units brought up by the enemy.

The neighboring armies, more than 100 km behind us, not only could not help us, but also needed help themselves. The 3rd Shock Army, stretching along its right border, at that time continued fighting for Kholm and on the approaches to Velikiye Luki, and the 22nd Army, with its left flank units, conducted unsuccessful attacks against the Nazi garrison in the city of Bely. The insecurity of the flanks of the 4th Shock Army required the expenditure of forces to cover them, especially in the Nelidov area, and also necessitated the need to have significant reserves in case the enemy broke through our front and reached army communications. For these purposes, the 334th Infantry Division was used in full force, creating a defense in the Nelidovo and Ilyino areas.

The two rifle divisions intended to replenish the army - the 155th and 158th - were still on the way transferred to the 22nd Army, while the 4th Shock Army, which bore the brunt of several offensive operations in the direction of the main attack, did not receive a single replenishment. In this regard, the promise once made by the commander of the Northwestern Front, Lieutenant General Kurochkin, that if our army managed to break through the enemy’s defenses, it would receive as many reinforcements as was requested, looked very strange.

Since February 6, the situation at the army front has stabilized, and the fighting began to be private.

Thus, the goal of the army operation - reaching the area of Velizh, Surazh, Demidov - was fulfilled, and the fighting at this line not only attracted the enemy’s large strategic reserves (up to six divisions), intended for the spring offensive, but also inflicted serious damage. A convenient springboard for the development of offensive actions in the future was also occupied.

During the period from January 9 to February 5, troops of the 4th Shock Army conducted two operations: Toropetsk and Velizh. As a result of the success of these operations, army troops wedged themselves into the junction between army groups “Center” and “North”, cutting two roads: Velikie Luki - Toropets - Nelidovo - Nevel and Velizh - Dukhovshchina - Yartsevo. The army entered an area that was most advantageous for striking the flank and rear of enemy troops operating in both the Moscow and Leningrad strategic directions.

An important result of the battles was that the 4th Shock Army turned out to be much closer to the “triangle” of the Vitebsk-Orsha-Smolensk highways than the fascist German armies operating in the Moscow direction, because the enemy’s Rzhev-Vyazma grouping was at a distance of 150–200 km from Smolensk.

The Toropets operation was completed exactly within the deadlines set by the army. The Velizh operation did not receive full development, mainly due to the lag of its neighbors and insufficient replenishment of the army with personnel, materiel and ammunition.

The further development of the Velizh operation, which followed immediately after the Toropetsk one, without a pause, was suspended, I repeat, due to the lag of neighbors, insufficient personnel replenishment and extremely weak material support. Even now I experience with pain in my soul that the further operation of the 4th Shock Army, which won victory in the hardest battles and created with its deep invasion a favorable environment for the further development of success in Vitebsk and Smolensk, stalled due to the fact that not a single one arrived person for strengthening. Is it possible for the front command to be so irresponsible in the organization and conduct of army operations! Both then and now I am convinced that Comrade will not be taken away from us. Kurochkin had three divisions, but on the contrary, reinforced with a couple of fresh ones, as he promised, I am sure that both Vitebsk and Smolensk would have been taken, and a different, more difficult situation would have been created for the enemy.

The main thing in leading troops is the ability to maneuver forces and means in order to always be stronger than the enemy in the right direction, creating the opportunity for our troops to realize victory. The command of the Northwestern Front, having such capabilities, apparently did not show the will.

During the 28 days of the offensive, the troops fought in a straight line 250-300 km, liberated about 3 thousand settlements and a number of cities, among them Peno, Andreapol, Western Dvina, Toropets, cut the Velikiye Luki - Rzhev railway, and inflicted serious damage on large forces the enemy, destroying the 416th and 453rd infantry regiments, the SS cavalry brigade “Totenkopf”, the reconnaissance detachment of the 123rd infantry division, the 251st and 253rd infantry divisions; inflicted a serious defeat on the 81st, 83rd, 85th and 406th Infantry Divisions, the 230th Reserve Infantry Division and one division (number not established) that was part of the 59th Army Corps (in full force thrown against the 4th Shock),

10th Infantry Brigade, 547th Infantry Regiment, 579th Landschutzbattalion, 50th Separate Battalion, 512th Railway Battalion, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 6th, 7th, 11th Fighter Detachments with a total strength of up to eight divisions, not counting the enemy units deployed to strengthen Vitebsk, Rudnya, Smolensk, Yartsevo and Dukhovshchina. The enemy lost at least 11-12 thousand in killed alone, not counting those covered in snow and prisoners, while our army lost 2,872 people killed and died from wounds.

During the entire operation, given the severity of the winter of that time (the temperature dropped below -40 degrees), 201 people suffered from frost, 423 people went missing.

During the offensive, the army captured large trophies: about 300 guns, approximately the same number of mortars, about 400 machine guns, over 1,200 vehicles, 2 thousand horses, about 1,000 motorcycles, about 1,000 bicycles, 300 railway cars, about 100 platforms, rich ammunition depots and food. During the operations, 40 enemy aircraft were shot down. Our losses in both operations were several times smaller.

At one time, the question was discussed about whether it was advisable to capture Vitebsk at that moment. Many said that the capture of Vitebsk was dangerous, because Velikiye Luki loomed over us on the right, and Rudnya, Smolensk and Dukhovshchina on the left. Proponents of trench warfare expressed similar objections. These people, lacking operational audacity, did not know how to develop strategic success. It was necessary to immediately turn the front in two directions, taking advantage of the extremely favorable situation that developed in February - March 1942, when the 4th Shock Army, in the form of a wedge, crashed into the territories occupied by the enemy. The first direction is Vitebsk - Velikiye Luki - Nevel with a simultaneous attack on Kholmy, Loknya, Novorzhev. The second direction is Vitebsk – Rudnya – Dukhovshchina – Smolensk. Needless to say, the operations ahead were difficult, but their success could be decisive for further military operations. It is unlikely that the Germans would have held out in Rzhev, Vyazma, and Sychevka. It is unlikely that they would have been able to intensify their actions in the direction of Voronezh - Stalingrad - the Caucasus, because then the powerful fist of the Red Army would have been brought from the north over their rear communications.

The offensive operations of the 4th Shock Army in difficult terrain and climate conditions allowed us to accumulate valuable experience in organizing an offensive, namely in relation to individual types of weapons, in the field of command and control, the work of headquarters, planning operations, organizing communications, party and political work with troops and local population, work among enemy troops, logistics and logistics work.

Particularly instructive in all respects were the actions of the 249th Infantry Division, which was in fact the striking force of the army, operating in the most critical sectors and managing to successfully complete the tasks assigned to it by the army command.

It is also impossible not to note the actions of the 360th Infantry Division, which has accumulated experience in overcoming inaccessible terrain and fighting in forests against well-fortified strongholds and pre-prepared enemy defensive lines.

A few words should be said about the work of the headquarters. The headquarters of the units and formations that took part in the operations varied in composition and preparedness; The headquarters of those formations whose troops already had combat experience turned out to be the most cohesive and efficient. Therefore, during the operation, the issue of leadership and control over the work of those headquarters that were staffed by officers who had no experience in staff work acquired particular importance during the operation.

The headquarters of the 4th Shock Army was mainly staffed with well-trained and efficient officers and proved to be a well-coordinated apparatus, capable of quickly and correctly solving problems put forward by the command, despite the lack of a reserve of staff officers.

Speaking about the work of the headquarters of the 4th Shock Army, one cannot help but recall the enthusiasm and speed with which the relatively young staff of this headquarters, fulfilling the directives of the front and the decisions of the army commander, developed a plan for their first, Toropetsk, offensive operation.

The planning of the operation, with the very hard work of the staff officers, and especially the head of the operations department, Lieutenant Colonel Beilin, was completed within three days.

The time to prepare for the operation was very limited. Therefore, simultaneously with the planning of this operation, army headquarters officers met the troops arriving in the army and escorted them to the concentration areas along the directions of their upcoming offensive. In addition, army headquarters officers conducted training with the command staff of the arriving troops and took measures to improve the supply of these troops with everything they needed.

One cannot help but recall, for example, how captain Portugalov and junior lieutenant Fetishchev, in very difficult conditions of off-road conditions, severe frost and snowstorm, not only accurately brought out the ski battalions assigned to them, but also provided them with all types of necessary supplies.

Regarding the work of the army headquarters in preparing the operation, it should be noted the very positive work of the communications department of the army headquarters under the leadership of Colonel (then General) K.A. Babkin, who, with the help of his dedicated signalmen, always and on time ensured fairly stable communications through several channels both upward and and with the troops.

I would like to cite the memories of ordinary signalman Kirpichnikov, who wrote to me about this period of his service.

“In mid-December, preparations began for some kind of big operation, which we, signalmen, guessed about from the revived activity of the headquarters. Communication units were intensively laying telegraph lines to the front edge. This work, to our surprise, went on during the day, without any camouflage from enemy aircraft. As it turned out later, the construction of lines was one of the command’s measures to divert the enemy’s attention from upcoming operations. In this way, the appearance of preparation for an offensive in the area of Lake Seliger was created. The army communications department, to which I was assigned, was preparing communications plans for the area adjacent to Ostashkov.

At the end of December, in severe frosts, the army headquarters and along with it our regiment began redeployment towards Ostashkov. The transfer took place in very difficult conditions, along snow-covered forest roads, and even off-road. The regiment's vehicles made part of the journey along the dismantled railroad bed, from which the sleepers had not been removed. Once the location for the command post was chosen, very busy work began. Signalmen, under the leadership of the head of communications, Colonel K. A. Babkin, intensively prepared documentation (call signs, keys), groups of telephone operators and telegraph operators were formed to organize communication centers at observation posts, command and reserve command posts. Communication was established with the arriving units. There was a lot of trouble, since divisions and brigades that were completely new to us arrived, sometimes located outside populated areas. The lack of cable for connecting lines presented considerable difficulties. The battle was literally for every reel. This deficiency was subsequently replenished by rich trophies.

It was January 9, 1942. After a deceptive silence, early in the morning the menacing roar of artillery preparation was heard. We signalmen tried to catch every message from the front line, where the enemy’s defenses were being breached. Finally, the telephone operators said: “Our people have moved forward, the Fritzes have run!” It became joyful. After all, before this, I must frankly admit, I often felt very bad at heart, especially when I read the reports of the Information Bureau - in many places our troops were retreating into the interior of the country.

Following the units, the army headquarters also moved into the breakthrough. His first command post on the territory liberated from the enemy was located in Velikoye Selo, not far from Andreapol. The first prisoners appeared. In those days they were a novelty for us. The German soldiers, in light uniforms not suitable for winter, looked extremely pitiful. Many were frostbitten and wrapped in civilian clothes.

Our troops quickly moved forward. The signalmen had difficulty establishing communications. It must be said that the main burden fell on the wireworms. Thanks to the efforts of the signalmen of our regiment and individual communications companies under the leadership of energetic commanders - Colonel K.A. Babkin, assistant chief of communications, Majors Sachkovsky (who died in 1944) and Tikhonov, commander

The 56th separate communications regiment of R. F. Malinovsky and other army headquarters in most cases had stable communications with divisions and brigades. The main operation was telephone communication and, to a lesser extent, telegraph communication: “Bodo” and “ST-35”.

At the beginning of February, the army command post was relocated to Staraya Toropa, or rather, to the village of Skagovo, 2–3 kilometers from the railway station. A new hot period began for signalmen, caused by offensive operations in the direction of Velizh. Extended communications required a sharp extension of communication lines. They especially lengthened after our troops captured Ilyino, Kresty and other points. This circumstance, as well as the increased actions of enemy aircraft, greatly complicated the work of the signalmen. Due to frequent bombings, cable and permanent lines were interrupted, and often they were disrupted by our tanks and vehicles, moving in a continuous stream from Toropets to the front line. Linemen often had to establish communications under heavy bombing, in deep snow, in forests. A particularly difficult task was establishing contact with the group of Major General V. Ya. Kolpakchi, operating in the direction of Demidov - Dukhovshchina, on the left flank of the army.

The hardening received during the attack on Toropets and Velizh served the personnel of the 56th Separate Signal Regiment well and hardened them. Many signalmen received government awards.

The days of offensive operations of the 4th Shock Army are unforgettable. They showed the strength and tenacity of the Soviet people, who overcame a well-armed enemy and the difficulties of an unusually harsh winter, and the ability of military leaders to lead troops forward. Our army fully justified the honorary title of shock and made a tangible contribution to the defeat of the Nazi hordes.”

The offensive began in January 1942. As it progressed, the prepared roads ran out and communications facilities fell behind. Wired communications (cable-pole and permanent lines) did not keep up with the troops and were often destroyed by enemy aircraft, and there was almost no field cable in the army. The radios were also lagging behind. Under these conditions, the army headquarters quickly switched to mobile means of communication (ski relay races, mounted officers from military headquarters to control communication centers), which provided information to the commander and army headquarters.

For the same purpose, as well as to assist the troops with the start of the offensive, officers from the operations department were sent to all formations of the first echelon, who provided regular information to the army headquarters about the progress of the offensive.

One of the features of troop control during the offensive was the nightly issuance of orders and combat instructions for the actions of troops for the night and the next day of battle or to clarify tasks if this was caused by the situation. These orders were delivered to the troops on time by headquarters officers. Cases of delays in the delivery of such orders to the troops were extremely rare.

In addition, the officers of the operational department of the army headquarters continuously monitored the progress of the execution of orders by the troops and often, especially in the battles of Toropets and Staraya Toropa, were among the troops, directly participating in the battles. This method of command and control of troops in those difficult conditions fully justified itself.

With the capture of Toropets, the army headquarters received captured motorcycles with sidecars, which dramatically increased the mobility of its officers. In addition, signalmen installed radio stations on captured all-terrain vehicles. These all-terrain vehicles subsequently always accompanied responsible headquarters officers when they went to the troops.

After the successful completion of the Toropetsk operation, the 4th Shock Army was transferred from the Northwestern to the Kalinin Front and immediately received a new mission.

There was only one night for the troops to sharply turn south and assign them new combat missions. During this night, in accordance with the decision of the army commander, the headquarters developed a new operation plan, combat orders, private combat orders, prepared maps of new areas of operation and immediately after approval by the army commander delivered them to the troops at night.

One cannot help but remember that some of the connections, and in particular

The 39th Infantry Brigade, Colonel Poznyak, was then operating behind enemy lines, and orders could only be delivered to them by plane. And this difficult and dangerous task was successfully completed by the headquarters officers. At the same time, the officer of the operational department of the headquarters, Colonel A. Soroko, distinguished himself with courage and resourcefulness, sent to the headquarters of the 39th brigade, which, according to his reports, was located in the village of Ponizovye. Having landed on the outskirts of this village, Colonel Soroko saw soldiers in helmets running towards him. He realized that these were the Nazis.

Shooting the fascists running up to the plane with a captured machine gun, the pilot quickly turned the plane around and lifted it into the air. After some searching for the 39th Brigade, Colonel Soroko finally found it on the spot and personally handed the army order to the brigade commander Poznyak.

Colonel Soroko and the pilot, who was slightly wounded in the leg, returned to the airfield with several dozen holes in the wings and fuselage of the aircraft.

Before the start of the offensive, the 4th Shock Army received two separate tank battalions for reinforcement: the 141st (consisting of 4 KB tanks, 7 T-34 tanks, 20 T-60 tanks) and the 117th (consisting of 12 MK-2 tanks , 9 MK-3 tanks, 10 T-60 tanks). There were 62 tanks in total, 30 of them light.

The tanks arrived in the army with half-used motor resources, while some tank crews had little knowledge of the new material. MK-3 tanks were not suitable for movement in deep snow; spikes had to be welded onto their track tracks using a makeshift method.

Terrain and climate conditions did not allow the widespread use of tanks; tank maneuver was extremely difficult.

Despite all the difficulties in using tanks, the 141st Tank Battalion cooperated well with the 249th Rifle Division in the battles for Okhvat, Lugi, Oleksino, Velikoye Selo and Andreapol. Our wonderful T-34 tank performed especially well, as before.

The 171st Tank Battalion almost did not participate in the battles, since at first it was attached, on the instructions of the front headquarters, to the 360th Infantry Division, which was advancing on the right flank of the army, and then, having received the order to move to the central sector, it was no longer able to catch up with the troops successfully advancing there .

The deputy army commander for armored forces, Lieutenant Colonel Malakhov, played a major role in the management of tank forces. He writes about this period of service:

“As part of the 4th Shock Army, I was appointed deputy army commander for armored forces. In this position, I participated in the Toropets operation of 1942. The army’s offensive began on January 9, 1942 and developed successfully, army troops captured the cities of Peno, Andreapol, Toropets, approached and surrounded the city of Velizh. As part of the 4th Shock Army, the tank forces were represented by the 141st and 171st separate tank battalions. With the approach to the city of Velizh, the 78th Tank Brigade arrived as part of the army troops. The tankers performed excellently, despite snow drifts and forested areas, as well as swampy areas. Many tankers were awarded government awards, in particular, the commander of the 141st brigade, Captain Kuzhilny, was awarded the Order of Lenin by the Front Military Council, and his deputy in the combat unit, Polovchene, was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union for exceptional feats.

In the battles of January 15, Captain Polovchenya, when the retreating fascist units were forced to move along a narrow road, along the edges of which snowdrifts of up to 1–1.5 meters had formed, crashed into the retreating columns in a T-34 tank, inflicting huge losses on them. The road was littered with abandoned equipment and hundreds of killed and wounded fascists. And when one of the fascists quietly climbed onto the tank of Polovchenya and tried to set it on fire with a combustible mixture, he did not lose his head, killed the fascist, put out the fire and continued to destroy the enemy with tracks and weapons.”

The combined arms artillery and reinforcement artillery coped well with their tasks. This was the considerable merit of the army artillery commander, Major General of Artillery Nikolai Mikhailovich Khlebnikov. This is a real combat artillery commander who knew how to think and act in relation to the most difficult situations.

He recalls this period:

“The 27th Army, renamed the 4th Shock Army, advanced in the Andreapol-Toropets direction and in two months broke through deep snow to a depth of 300 km, captured Andreapol, Toropets, Staraya Toropa and, having surrounded Velizh, advanced units reached Vitebsk .

The skillful use of ski battalions, supported by mobile mortar and artillery units on ski installations, made it possible to penetrate deep into the enemy's position and hit him from the rear and flanks. The artillerymen learned to operate so well in these harsh winter conditions that even the heavy regiments (152 mm howitzers) kept up with the troops.

With air defense the situation was more complicated.

Our entire anti-aircraft artillery consisted of only five divisions of 25-mm and 37-mm guns and two batteries of 76-mm guns. There were no means of communication for the warning network. The VNOS service used command communications. Anti-aircraft artillery often lagged behind the infantry and suffered from a lack of ammunition, although this need was partially overcome by the anti-aircraft gunners by using enemy 37-mm shells. It must be said that of the 29 aircraft shot down by anti-aircraft gunners during that period, 19 were the share of the 615th separate anti-aircraft artillery division, commanded by Captain Kalchenko.”

It should also be noted that the 4th Shock Army included the Army Air Force, which consisted of two regiments of Po-2 night bombers, one SB regiment, and two fighter regiments. Hero of the Soviet Union, Colonel Georgy Filippovich Baidukov, was appointed head of the Air Force of the 4th Shock Army in December 1941.

The Air Force played a positive role in the Army's offensive operation. The army had, as already mentioned, only 53 serviceable aircraft at its disposal. The enemy always had air superiority. The lack of forces to equip an airfield near the front line led to the separation of our aviation, already small in number, from the advancing troops. Unfortunately, this did not allow us to accumulate and generalize any significant experience in the use of aviation when conducting offensive operations in winter conditions and difficult wooded terrain. However, our pilots did not allow the air enemy into the unloading areas during the concentration of units, and skillfully covered the troops on the march. In preparation for the offensive, our aviation influenced enemy concentrations, their strongholds both at the front line and in the depths of the defense. During the aviation offensive, the task was set to cover the main grouping of army troops along the axis of movement of Ostashkov, Peno, Andreapol, Toropets, Velizh. The cover-up was, however, insufficient for reasons already known to the reader. Through assault operations, the fighters destroyed the retreating enemy and tried to prevent the approach of his reserve. Night raids by our bombers exhausted the enemy in concentration areas and in defense.

There were many shortcomings in the recruitment of air force units during combat operations. According to the very strange situation that existed at that time, air units were not systematically replenished with either materiel or personnel, but were completely replaced when all the aircraft failed. It is not difficult to understand that with such a system the army often found itself completely without aviation. And then new people arrived who did not know either the conditions of the combat situation or the terrain, so they were of little use. If we add to this a number of smaller shortcomings, such as the fact that first the new flight personnel arrived, and after some time the technical ones, then it is not difficult to understand how much such a vicious organization reduced the combat effectiveness of the already weak army air forces.

Valuable experience was gained in the use of ski battalions, which performed well in a number of battles, in particular during the capture of Staraya Toropa.

The conduct of both operations, especially Toropetsk, made it possible to further strengthen ski training among the troops.

During the preparation and conduct of the operation, much attention was paid to party political work.

Before characterizing this most important area of troop leadership, I would like to cite a letter sent to me by former army political worker Efim Kononovich Dzoz.

“I transferred to the 4th Shock Army from the 27th, like many other officers who served in this army. At that time I worked in the political department. The head of the political department at that time was divisional commissar Semenov, a very demanding and strict political worker, he spoke very briefly, but clearly and understandably. He gathered the entire apparatus of the army's political department and announced that the 27th Army had been renamed the 4th Shock Army, and told us about the upcoming tasks that the army must perform during offensive operations.

The order from Headquarters to rename our army encouraged all of us, since it was clear that our army was entrusted with large and responsible tasks to defeat the German invaders and that in this direction our army would play the main and decisive role. On the same day, everyone was informed that you had been appointed commander of the army.

I remember such a case. When the redeployment of troops took place, many commanders and political workers of the army were sent to army formations to convey to the personnel the order of Headquarters and the tasks that had to be completed. The morale among the personnel was extremely high. Everyone was burning with the same desire to quickly launch an offensive and achieve the goal.

Despite the harsh December winter, impassable roads and lack of transport, people walked and marched in snowstorms and forty-degree frosts for the sake of victory over the enemy. These high and noble deeds of the soldiers of the 4th Shock Army did not remain without a trace.

Concentrating army troops for an offensive is a complex and difficult task. It was difficult because it was solved in a short time and in harsh winter conditions.

By order of the Army Military Council, on December 29, a group of army staff officers and political workers, including battalion commissar Konotop and I (I don’t remember the names of the other comrades), arrived at the headquarters of the 249th Infantry Division to assist in conveying the order to the personnel. We stayed for three days in total and on January 1, 1942 we returned to army headquarters.

The division commander, Colonel Tarasov, listened carefully to the senior group and then spoke about the combat readiness and political and moral state of the division’s personnel. He was a highly cultured and sincere person, a smart and disciplined officer. The conversation was interrupted by a telephone call. Someone was passing on intelligence information, and he smiled and said in response: “Well, that’s good, our assumptions were confirmed,” after which the whole group of officers went to their units. Talking with the soldiers and commanders of the division, we were convinced that the units were seriously preparing to carry out the combat mission, the soldiers were in a good mood, there was a high morale and the desire of all personnel for one goal - to quickly launch an offensive.

The head of the department for work among enemy troops of the army's political department was the senior battalion commissar Nemchinov.

During the period of offensive operations, Nemchinov, together with the employees of the department, put a lot of effort and initiative into carrying out this important work. She did not remain unsuccessful. It is no coincidence that the Nazis surrendered relatively often for this period of the war, and many of them kept with them propaganda leaflets that were published by the 7th department.”

What E.K. Dzoz told about working among enemy troops can be supplemented with several more facts. Skiers and scouts of the 334th Infantry Division alone scattered 350 thousand leaflets and newspapers at enemy locations. This matter was handled well in the 249th Division. During the offensive, a powerful radio installation sent by the political department of the front operated as part of the army, which conducted dozens of transmissions for enemy troops. The program of such radio broadcasts included speeches by prisoners, an appeal from the Soviet command to German soldiers with a call to surrender, etc. Judging by the testimony of prisoners of war, these radio broadcasts were of great interest to enemy soldiers. There were times when they stopped firing, climbed out of their dugouts and listened to the broadcasts.

Our scouts, having scattered leaflets and disguised themselves, more than once observed how German soldiers secretly from their superiors picked up leaflets, read them, and then hid them. Our leaflets were found among those killed and captured, hidden in their belongings or documents. The prisoners, however, said that they were afraid to share the contents of the leaflets with anyone, as this threatened them with execution. When our leaflets were discovered, Hitler’s command gave orders to write on them: “enemy propaganda” and immediately hand them over to officers.

Our scouts, participating in battles from the beginning of the war until the capture of Staraya Toropa, never encountered defectors among the prisoners. The confidence in success created by fascist propaganda, confirmed by easy victories in the West, led in the first months to the fact that we were able to capture prisoners and even documents with great difficulty. The captured prisoners considered themselves doomed, since they had it drilled into their heads that “the Russians shoot all prisoners,” and during interrogations they behaved defiantly and sometimes ridiculously impudently. Thus, one Bavarian prisoner of war, captured on the Western Front, stated during interrogation that they came to us with the war “to restore order.” His statement sounded like a paraphrase of the famous legend about the calling of the Varangians. He said: “Russia is a big country, but you rule it poorly.” This was not the only attack.

The very first blows of our army began to knock down the arrogance of these “invincibles”. The surrender of an entire company to one platoon is an indicator of fear. A critical revision of the version of the “cruelty” of the Bolsheviks, disseminated by the fascists, also began. One of the first defectors who crossed over to us near Staraya Toropa, when asked why he crossed over and did not retreat with others, replied that it was not yet known whether those who retreated would be able to escape. “Our lieutenant spoke about the destruction of prisoners, but I knew that this was a lie. When I was drafted into the army, my father said: “If there is war, then there is captivity, and the Russians kill only those who resist with weapons,” so I gave up my weapons.”

Corporal of the 189th Regiment of the 81st Infantry Division, Herbert Ulyas, when asked how he was captured, said: “When the officer told us that the Russians were coming and that we needed to get out of here as soon as possible, I replied that I wouldn’t go any further, let them come.” Russians, and I will go over to them. There was another corporal and one chief corporal with me. The officer began to rush us. When the Russians showed up, the officer and some of the soldiers ran to the right, and the three of us ran to the left. The officer fired and the bullet hit me in the arm, but I still surrendered.”

Another corporal from the 83rd division said: “We surrendered because we were morally depressed, hungry, freezing and decided that it was better to work in Russia than to fight in such conditions.”

It must be said that letters from Germany also contributed to the voluntary surrender. Thus, the father of Herbert Freilich, a soldier of the 105th Infantry Regiment of the 253rd Division, wrote to his son: “Your great-grandfather was in Moscow in 1812, but he survived by force. And you, as his great-grandson, follow in his footsteps. Try by all means to preserve yourself and it is better to be captured than to be killed.”

However, the overwhelming majority of the soldiers, although they expressed hidden dissatisfaction with the war due to difficult conditions, continued to remain intoxicated by fascist propaganda. In front-line units, discipline was quite strong, cases of indiscipline were rare. The prestige of officers remained high.

All our other political agencies also worked harmoniously and effectively.

As soon as the order to go on the offensive was received, political workers quickly conveyed its contents to every soldier and commander. On January 8, on the eve of the offensive, employees of the army’s political department, after appropriate instructions, departed for formations. During the operation, they were in critical areas, maintaining a high offensive impulse, assisting unit political workers in developing propaganda work and directing all party political work to successfully support the combat orders of the command. Much attention was paid to the management of daily party work in company party and Komsomol organizations, as well as assistance in establishing the supply of ammunition and food.

Party and Komsomol meetings were held in all units and divisions with the question of the role of communists and Komsomol members in the upcoming offensive.

Special mention should be made of the political department of the 249th Infantry Division, which worked flexibly and purposefully throughout the entire operation. Being constantly aware of events, the political department solved specific problems. His representatives in the units not only controlled the work of political workers, but actually ensured the implementation of combat missions in a certain area.

The political department of the army paid great attention to organizing the work of the rear. Considering the enormous importance that roads have in this matter, political agencies of the rear units assisted the command in ensuring the repair and restoration of roads.

Printed propaganda was also good in the army, in particular the work of the army newspaper “The Enemy on the Bayonet”.

The newspaper of the 27th Army “Battle Strike” (later renamed the newspaper “Enemy on the Bayonet”) was created in the last days of June 1941 in Riga. From here she began her journey with units of the 27th Army. Nikolai Semenovich Kassin headed the newspaper “Battle Strike” from the first days of its existence. The main core of the editorial staff consisted of students sent from Moscow to retraining courses for army newspaper workers at the Military-Political School named after. V.I. Lenin and a group of local Latvian journalists.

In the difficult days of the defensive battles of 1941, the newspaper “Battle Strike” wrote on its pages about the stamina, courage and bravery of the Red Army soldiers who defended their Motherland with their breasts. Together with units of the 27th Army, the newspaper staff fought through Latvia, the Leningrad and Kalinin regions.

Neither headquarters nor editorial offices were located in populated areas at this time. Their place was in the forests. All printing equipment was located in specially adapted vehicles. And at first, before supplies were organized, the editors carried all their supplies of newsprint and printing ink with them. These supplies were replenished by evacuated regional newspapers. The staff of the printing house was also staffed by city and regional newspapers. The editors hired typesetters and printers in Ostrov and Lokne, paper in Kholm, and a printing press in Staraya Russa. It was a formative period.

In the fall of 1941, when the front line stabilized and our units were gathering strength for decisive battles, the editorial office “emerged” from the forests and began to locate in populated areas.

Only the editor, his deputy, and secretariat workers were constantly in the editorial office. The rest of the editorial staff alternately stayed in units. If one group of editorial workers returned from units, the next day the other was sent to the front lines. The length of stay of correspondents in the editorial office was, as a rule, three to five days. During this time, they managed to write about everything they saw and learned at the forefront. This system of work allowed the editors to have fresh materials on the combat operations of the units every day. In addition, the editor had a reserve that he could promptly send to one or another unit.

In addition to the materials organized by the staff, the editors received a large number of letters from soldiers and officers who helped the newspaper better cover the combat life of the units. The newspaper published letters from military officers in every issue. Military correspondents worked more actively during the period of defense.

During the days of the offensive, the newspaper “Enemy on the Bayonet” published daily operational reports on the advancement of army units, reports on the military operations of companies, battalions, regiments, on the courage and heroism of soldiers and officers. In order to get from the advancing units to the editorial office, correspondents used any type of transport: passing vehicles, fuel trucks, tanks, ambulances. And it’s not for nothing that the following poems later became popular among front-line journalists:

Are you alive or are you dead?

The main thing is that in the room

You managed to convey the material.

And so, by the way,

There was a “wick” to everything else,

And don't care about the rest.

Sometimes, without having time to write or type a message, the military journalist dictated it directly to the typesetter.

War correspondents also went along with the units, so that later they could convey on the pages of the newspaper the courage and bravery of the soldiers, their hatred of the enemy, and selfless devotion to the Motherland. Often they, together with companies or battalions, went into battle, repelling enemy counterattacks with weapons in hand. And it is no coincidence that Major G. A. Tevosyan (an employee of the editorial office of the newspaper “Enemy on the Bayonet”) was presented with the government award of the Order of the Red Banner by the command of one of the regiments of the 360th Infantry Division. Government awards for military services to the Motherland were given to majors A. Drozd, A. Goncharuk, I. Yandovsky, captains I. Zaraisky,

R. Akhapkin, Lieutenant Colonel V. Titov, who became the editor of the army newspaper “Enemy on the Bayonet” after N. S. Kassin left for the front-line newspaper, and many others.

Covering offensive battles, the newspaper did not limit itself to short information about occupied settlements and trophies. The pages of the newspaper showed the high moral and fighting qualities of the soldiers of the Red Army, and promoted the combat skills of the best soldiers, officers, and units.

The editors of the newspaper “Enemy on the Bayonet” had good contact with

7th branch of the army's political department. Based on Nemchinov’s materials, the newspaper published many interesting materials showing the face of the Nazis. I remember the articles “Battalion of Criminals in the Square” (about one unit of the Nazis, formed from criminals), “Frau and the Herrs are groaning” (about letters to the fascists from the rear of Nazi Germany).

The editorial staff lost many comrades during the war years. Among them are the writer B. Ivanter, deputy editor I. Kaverin, printer V. Antonov and others.

There were also shortcomings in the work of political agencies, mainly due to the lack of experience of the majority of political workers.

An unusually high offensive impulse, courage, dedication and devotion to the socialist Motherland - that was what was truly a massive phenomenon in the 4th Shock Army in those days. I would like to again remember the courageous, persistent and disciplined 249th Infantry Division. During the offensive, it became even more tempered, and many heroes emerged from its ranks. Lieutenant Mishkin is a master of unexpected raids on the enemy, Lieutenant Colonel Nazarenko and Captain Andreev are combat commanders of the vanguard units, battalion commissar Gavrilov, political instructor Cherenkov are real political leaders and leaders.

Here we should remember the kind words of the Chief of Staff

249th Infantry Division Colonel N.M. Mikhailov, now a retired major general. A good organizer and closest assistant to division commander Tarasov, he did a lot for victory. Ordinary soldiers and junior commanders also distinguished themselves, such as Sergeant Velikotny, Sergeant Fartfuddinov, who destroyed dozens of Nazis, and scouts Devyatkin, Malikov, Prilepin and Polyakov, who destroyed up to 70 enemy soldiers in just one battle. The group of artillerymen showed remarkable resourcefulness. Under heavy machine-gun fire, they crawled to a 105-mm battery abandoned by the Nazis and, turning their guns, opened fire on the enemy. More than a hundred German shells were fired by brave artillerymen, destroying six machine-gun points and 10 enemy vehicles.

Even when a difficult situation was created, the warriors did not lose their composure, fought bravely and inflicted heavy damage on the enemy. In one of the battles, more than a company of Nazis, supported by machine gun and mortar fire, attacked Lieutenant Dedov’s battery on the flank. The battery commander turned his guns and met the enemy with volleys. As a result, up to 50 enemy soldiers and two mortars were destroyed. The Nazis fled without looking back. The soldiers of the 332nd Infantry Division fought bravely, and the personnel of the 358th, 360th Infantry Divisions and other army formations performed well.

The troops of the 4th Shock Army liberated several hundred settlements from the Nazi invaders. Residents of cities and villages joyfully welcomed the return of their native Red Army.

We helped local organizations restore Soviet and party bodies, organize their economy, and restore order. Local residents provided material assistance to army units. So, in the village Beglovo collective farmers provided the entire battalion with food for two days. In the village of Kolpino, Zaborovsky Village Council, the population gave us (360th Rifle Division) 20 pounds of rye, 86 pounds of potatoes, fodder and allocated 13 horses for its transportation. In the village of Grishino, collective farmers decided to repair bridges and clear roads to ensure the fastest possible advance of troops.

The deputy head of the army intelligence department, and then the head of the department, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Mitrofanovich Bykov, now a retired colonel, shared with me his notes from that time:

“Big frosts (23.12–28°, 26.12–32°) brought great hardship to our units and units, frostbite appeared, and almost the entire headquarters and political department of the army were thrown into units to help the headquarters of the formations organize temporary housing and rest for the troops. In particular, I was sent to Mishchenko in the 334th Infantry Division. We organized the construction of huts and insulated them with spruce branches. They taught soldiers how to make smokeless bonfires “Nodi”. The soldiers, having removed the snow to the ground inside the hut, used it to line the walls outside, and inside they made a fire from two logs 1.5–2 meters long, laying them one on top of the other with a gap of 3–5 cm, lighting a fire in this gap. These logs, smoldering, gave almost no smoke, turned into coals, and the temperature in the hut was above zero and bearable.

At the same time, reconnaissance platoons of rifle regiments and reconnaissance officers of the division headquarters were briefed. The intelligence officer of the division headquarters here was Major Chuikov, a brave, energetic comrade. Subsequently, he was appointed deputy chief of the army's intelligence department. Chuikov was well versed in the situation and, acting through the lake. Volgo, with his scouts, quickly and basically correctly determined the outline of the front line of the enemy’s defense and the location of his firing points, which then contributed to the successful action of the division.

I also remember such a very characteristic episode, testifying to the high fighting spirit of our soldiers and officers, their determination to complete any combat mission. Through the lake Seliger from the village. The heat was to be crossed over the ice by the 360th Division, 48th Rifle Brigade and tanks. The ice turned out to be not strong enough to allow tanks through, and it was decided to increase it. To cover these works and further joint actions in the Zaborye area, the 66th ski battalion was concentrated on January 10. To check its readiness and security, I was sent by the army commander to this battalion.

My all-terrain vehicle failed. I went on foot, then got a horse and rode it 24 km there and back. I drove along roads under enemy control. A little scary, but, in general, nothing. Found a battalion in Zaborye. People are hungry, but the mood is fighting. By midday the battalion reached its area, where it was supposed to receive food. The trucks with food were stuck in the snow on the ice of the lake, and by the time of the performance the battalion had not received food.

Acting on behalf of the army commander (confirming the importance of the events with an all-terrain vehicle, which by this time was familiar not only to the commanders of formations and units, but also to many privates), I obtained from the commander of the engineer battalion a cargo sleigh with horses for food, having organized the reloading, I myself and two soldiers left forward to the battalion. Having passed through the island and reached the western shore of the lake, we carefully moved along the path, which, apparently, had been paved by German patrols. I found a battalion of skiers concentrated at a small forest guardhouse east of Zaborye. Here the battalion commander, a very young captain Andreev, announced the task to the company commanders and gave the combat order to march. Not a word was said about the fact that the soldiers, and even the commanders, were hungry and there was no food; there was no talk about food in the units. Both commanders and soldiers listened to the order with full attention and determination to carry it out. The untimely delivery of products, according to the battalion commander, was obviously caused by some unforeseen circumstances. “I’m sure,” said the battalion commander, “that the food will soon catch up with us.”

The battalion coped with its task perfectly, but the battalion commander died a glorious death while trying to intercept the Surazh-Vitebsk - Vitebsk road.” Further, from the records of Colonel A. M. Bykov, it is possible to reconstruct a picture of the work of army intelligence.

Ski battalions played a major role in reconnaissance throughout the offensive operations. Making extensive use of their maneuverability, small detachments of skiers entered the enemy's rear through forests, captured prisoners and documents, which gave the army command and staff the opportunity to timely unravel the enemy's plans, especially his attempts to bring up reserves or escape from attack to a new line.

All army troops very quickly developed the desire to help intelligence officers study the enemy. The army's intelligence department received a lot of different documents - soldiers' books, letters, diaries, orders. There were cases of delivery of cigarette labels and recipes, and the heads of intelligence of regiments and division headquarters quickly understood the need to systematize the selected documents and correctly indicated the points of their extraction. The study of these documents greatly helped to reveal individual attempts by prisoners, especially officers, to mislead and misinform us.

Using documents, comparing data obtained from documents with the testimony of prisoners, the army's intelligence department was able to correctly assess the enemy and took advantage of this opportunity.

The head of the 3rd information department was Major Kondakov, a very thoughtful, serious intelligence officer, who had an exceptional memory and a very good rule - to write down in a special book, by the way, started by him, the symbols of enemy units and formations - “oak leaf”, “bear” "", "mountain flower", special, characteristic features in the actions of these units, their numbers, weapons, losses and reinforcements, etc. This assisted in assessing the enemy already during the first offensive of the army and was of exceptionally great importance for the study and assessment enemy in the future. Working in close contact with the translator Captain Markov, Major Kondakov, in a tense situation, knew how to promptly inform the division headquarters about new information about the enemy, whenever possible, and continuously kept the headquarters departments and headquarters of the military branches informed about the events in the army’s offensive zone.

A significant role in reconnaissance of the enemy was played by the 2nd branch of the intelligence department - chief Major Glazkov, assistant captain Evstafiev. Through the intelligence officers of this department, the intelligence department promptly, even before the capture of Andreapol, received detailed information about the garrison of the city and the warehouses that were concentrated there.

Lieutenant Colonel A.N. Guselnikov, who was mortally wounded near Velizh by a shell fragment (in December 1942), left a good memory of himself. It seems that there was not a single reconnaissance platoon where the political officer had not visited, explaining the goals and objectives of reconnaissance. Being an experienced intelligence officer himself, he skillfully directed the actions of reconnaissance units.

We also had things that slowed down the work of intelligence, such as, for example, the almost complete absence of translators not only in rifle regiments, but also in division headquarters. This often prevented the command of regiments and divisions from using fresh information about the enemy immediately after capturing prisoners or documents, and sometimes home-grown translators incorrectly translated the testimony of prisoners, which created confusion.

In the rear of the Nazi troops operating in front of the army front, there were several partisan detachments. During the month of its combat activity, up to a hundred people joined the Penovsky detachment. This detachment's combat record included many destroyed enemy vehicles, blown-up bridges, and killed enemy soldiers and officers. The Serezhinsky partisan detachment raided the Nazi garrison in the village of Usadba and destroyed 40 enemy vehicles there.

The headquarters and political department of the army kept close contact with the partisan detachments, assigned them combat missions, and supervised their political work among the population. Specially trained comrades were sent to partisan detachments. While disrupting enemy communications, the partisans also carried out a lot of work among the population.

The activity of the partisans especially intensified when our offensive unfolded. Partisans came out of the forests to provide direct assistance to Soviet units. They guarded the villages from the enemy, who sought to burn everything during their retreat.

The rear of the army did a tremendous amount of work during the operation. There is no need to say much about the complexity of their activities. It can be said directly that the material supply of the army, especially food, and partly fuel and even ammunition, was provided at the expense of the enemy.

On February 13, when the army troops successfully completed the Toropetsk and Velizh operations, I surrendered the army to Lieutenant General F.I. Golikov and went to the hospital.

Many participants in the Taropetsk and Velizh operations were deservedly awarded. The majority of company and battalion commanders and all regimental and division commanders received awards. The commander of the 249th Division, who particularly distinguished himself in battle, received two orders. The awards were received by the commanders of the military branches, the chief of staff of the army Kurasov, and a member of the Military Council Rudakov.

Many years have passed since then, but I am still proud that I had the honor of commanding the 4th Shock Army, which successfully participated in the Toropetsk and Velizh operations and completed the tasks assigned to it in incredibly difficult conditions.

I was admitted to the hospital, which was located in the building of the Agricultural Academy. Timiryazev, the same one where I was treated after being wounded on the Bryansk Front.

The care here was still excellent. Doctors and other medical workers showed me great care and attention.

During my stay in the hospital, I was visited by many military, party and Soviet leaders with whom I had the opportunity to work together or come into close contact through service, party and Soviet work. So, I was visited by comrades P.K. Ponomarenko, K.V. Kiselev and others - from Belarus; A. Yu. Snechkus, M. A. Gedvilas, Yu. I. Paleckis and others - from Lithuania; From the military there were comrades A.V. Khrulev, F.N. Fedorenko and many others.

I received a lot of notes and letters: they had different contents, but they had one thing in common - to quickly achieve victory over the enemy. Many letters expressed a desire to take a personal part in bringing victory closer.

The hospital was often visited by teams of Moscow artists who performed in the club, and for bedridden patients - right in the wards; we had workers from Moscow factories and collective farmers from villages near Moscow. Complete strangers came into the room, but the conversation started, and after 5-10 minutes it seemed that you were talking with someone close to you. Everyone had the same thoughts - to defeat the enemy.

In all this, our party’s concern for people who were temporarily out of action was visible.

Serving in the 4th Shock Army ended the first period of my activity during the war years, associated with the Western direction. After recovery, I was appointed commander of the front operating between the Don and Volga rivers.

On December 13, an offensive began on the right flank of the Soviet troops stationed on the border of Belarus - the Gorodok offensive operation of the 1st Baltic Front under the command of I.Kh. Bagramyan.

“On the morning of December 13,” recalls the commander of the 1st Baltic Front, Marshal of the Soviet Union I.Kh. Bagromyan, - on the day of our offensive it became warmer again, the sky became cloudy, visibility deteriorated to critical, and the commander of the 3rd Air Army, Lieutenant General of Aviation M.P. Papivin reported to me that using aviation would be very difficult. Thus, the artillery task became more complicated... The artillery preparation of the front line, which began at 9.00, lasted two hours, but with interruptions, because there was not enough ammunition. Then the fire was transferred to the depths of the defense. At the same time, the rifle units moved into the attack.”

To stop the advance of the Soviet troops, the Nazi command transferred new reinforcements to Vitebsk - two infantry divisions. Relying on the defensive lines with which Gorodok was fortified, the enemy offered stubborn resistance. Three lines of defense were created on the approaches to the city.

In the direction of the operation, the Soviet command was waiting for frosts that could facilitate the advancement of tanks and other equipment through the swampy terrain. However, the tankmen of the 5th Tank Corps, operating here as part of the 1st Baltic Front, also sought other ways to overcome the swamps. So, if in Rokossovsky’s troops the infantrymen made peculiar “wet foot” skis, then the tankmen of Bagramyan’s 5th Tank Tank mounted special additional plates on the tracks, increasing their width by about 1.5 times. The tanks carried fascines, logs, and additional cables.

The enemy held 1 tank division and 8 infantry divisions on the Gorodok ledge, and also had 120 tanks and 800 guns and mortars here. The 5th Tank Corps already had experience in fighting in this direction, and not entirely successfully. In November 1943, the 24th brigade of the corps, fighting a night battle (one of the new tactical methods of Soviet tank crews), broke into Gorodok. However, it was not possible to consolidate and develop success then.

On December 13, the 11th Guards and 4th Shock Army (which included the 5th Tank Corps) began the Gorodok offensive operation. The 4th Army, unlike the 11th Guards, was able to break through the main line of enemy defense. However, the pace of the offensive soon slowed down - Soviet troops came under fire from 25 enemy batteries, and the actions of the tanks were complicated by the onset of a thaw. But on December 14, the 1st Tank Corps was brought into battle on the right flank of the 11th Guards Army. On December 16, he reached the Bychikha station, where he linked up with the 5th Tank Corps. Thus the encirclement of the enemy's 4 infantry divisions was completed. Skillfully holding back the pressure of enemy tanks trying to break through the encirclement ring, the 41st Tank Brigade of Colonel P.I. Korchagin 5th shopping mall. The tank crews of the 70th Tank Brigade showed particular courage in the battle for the station. Tank of junior lieutenant V.V. Martens, for example, were rammed by an enemy train trying to leave the station.

Commander of the 1st Baltic Front I.Kh. Bagromyan wrote: “Despite unsatisfactory weather conditions, which were completely excluded by the actions of our aviation, the 11th Guards, 4th Shock and 43rd armies broke through the German defenses on a 15-kilometer section of the front and on December 16 advanced 25 km deep into the enemy’s defenses The 1st and 5th tank corps brought into battle (commanded by generals V.V. Butikov, M.G. Sakhno) surrounded units of the enemy’s 4th infantry division in the Bychikha station area, which was defeated. Until December 20 Soviet troops liberated more than 500 settlements.

Army General I.Kh. Bagromyan also pointed out in his memoirs the failures during the offensive operation. So he noted: “Nevertheless, we did not achieve the full expected successes. The town was not taken, and our plan to encircle the main enemy forces defending on its outskirts was in jeopardy. The enemy skillfully maneuvered and stubbornly resisted. The matter also became more complicated. "the need to withdraw the 1st Tank Corps from the battle. Unfortunately, shortcomings in troop management also emerged. I had to go to the command post of K. N. Galitsky and provide him with assistance on the spot."

Marshal Bagramyan recalls: “The decisive battle for Gorodok began on December 23, 1943. Before the attack, reconnaissance in force was carried out. It identified the most dangerous centers of German resistance. At 11.00 o’clock on December 23, artillery preparation began. After an hour’s artillery preparation, formations of the 11th Guards went on the offensive and the 43rd Army. Fierce hand-to-hand fighting broke out in the trenches and passages of formations. The battle lasted 36 hours and was fought not only during the day, but also at night."

The attack was not easy; the Nazis clung to the city, which was an important strategic railway junction. THEIR. Bagramyan recalled: “The attack of the guards was fierce and unstoppable. Having crossed the riverbed on ice, they broke into the northern outskirts of the city. The battalion of Senior Lieutenant S. Ternavsky was the first to do this. The fighters of the nearby battalion of Senior Lieutenant F. also performed well in the night battle. Merkulova He and his political commander, Captain Rudnev, were inseparably in the ranks of the attackers, inspiring them by personal example.

Having burst into the city, both of these units fought assertively and boldly: breaking through to the flanks and rear of strong points, they fired at them with continuous mortar and machine-gun fire. Suffering heavy losses and fearing isolation and encirclement, the fascist garrisons began to flee. Seeing this and not having free reserves, the enemy command withdrew part of the forces from the eastern front of the city perimeter. This was immediately used by Major General A.I. Maksimov, commander of the 11th Guards Division. He put machine gunners on several tanks assigned to him and threw them on the south-eastern outskirts of the city. In a short but fierce battle, tankers and machine gunners knocked out the Nazis, who were holed up in stone houses turned into pillboxes."